RAF Swinderby Fuzing Point Shed

Across the country bit by bit most of our Bomber Command airfields are disappearing, but thanks to the work of the various Heritage Centres and Museums up and down the country some parts are being preserved for future generations some Airfields have all but gone completely now, only small pockets of their previous use remain.

One such pocket was discovered at the now disused RAF Swinderby, the owners of the land had no idea of the history of it when it was bought as Industrial Land to set up a factory. Indeed the site seemed well away from any remaining sections of the airfield. The whole site had been cleared when the owners went to view it, the surface scraped and piled on the very far boundary which was covered in brambles and rubble, so no one thought to look beyond the pile of debris, until one lunchtime some bored employees decided to clear a path through and explore…to their surprise they found part of a very derelict building, obviously someone had previously tried to destroy it as most of the supporting struts had been cut through and removed. Just enough was left to photograph and record for the archives, and with the help of the Airfield Research Group it was identified as the RAF Swinderby Fuzing Point Shed, (Part of a Type C bomb store from the original 1940 layout).

Introduction

To commemorate the site’s earlier history Di Ablewhite, Alan Morris and Celia Morris started to investigate what remains of one of the Fuzing Point sheds which was part of RAF Swinderby’s Bomb Store. They are recording as much as they can before it disappears altogether. Working with advice from the Airfield Research Group, and particularly with the help of Peter Hamlin, the following information has been obtained for archive.

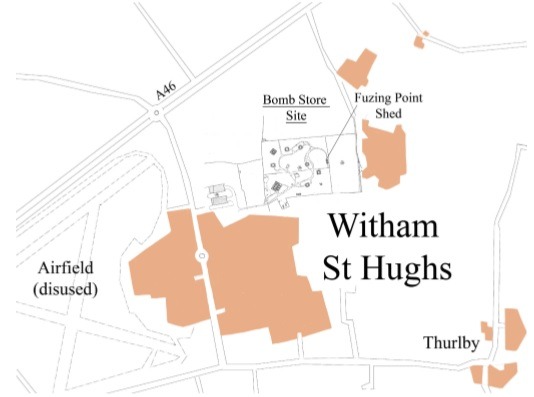

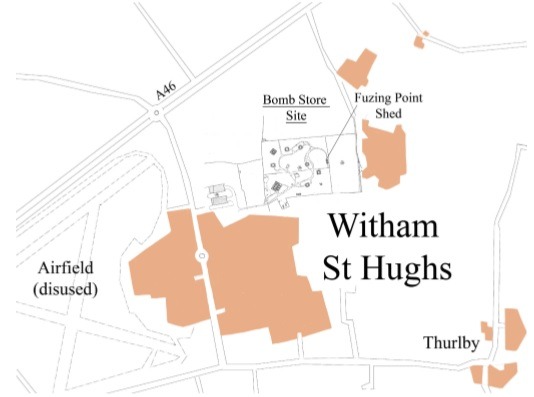

Location – SK 89641, 62658

Rough plan to give an idea of approximate location (not to scale)

Dimensions of Swinderby Fuzing Point Shed

Length – 66ft Width – 16ft Head Height – 7’ 9”

Manufacturer – Dorman Long & Co. Middlesbrough, England

Photo showing inside of a similar Fuzing Point Shed

Similar view into the remains of the Swinderby Fuzing Point Shed

The following information and descriptions have come from Peter Hamlin who was an RAF Armament Fitter albeit post-war (1956 – 1970). He worked in bomb stores amongst other tasks so ‘missile preparation’ including bomb fuzing was part of his job.

Practically all structures on a military airfield in the British Isles were prescribed by an Air Ministry drawing with a unique number. For example, the ‘Bomb Store 50 ton Type C’ on this site was AM Drawing No 5416/40 and the Fuzing Point shed was (probably) 15963/40 Fuzing Point Heavy or 15964 Fuzing Point Light. The difference was in the internal shelves, racks and drawers to suit components for ‘light’ or ‘heavy’ bombs. The standard Nissen came in 16 feet width and 24 feet width, the length being in multiples of 6 feet, usually six sections, so 36 feet long. Fuzing Points were usually 60 feet long to take a train of trolleys. (Swinderby’s is 66 feet long.)

The frame consists of Tee section steel curved ribs with timber purlins. Internal and external sheeting was galvanised corrugated steel (better known as corrugated iron) laid horizontally. The end walls could be timber framing, timber clad or half brick. FP sheds were half brick with double width timber doors in timber frames at both ends, to enable bomb trains to be towed through. (Swinderby’s appears to be corrugated iron on a wooden frame.)

Photo showing exterior of southern end door with original camouflage paint

The earth traverses were to protect external structures and stores in the event of an accidental detonation. Technically they are known as ‘interceptor traverses’ because they are intended to catch and retain fragments of bomb casing. Surprisingly, a high explosive bomb sitting on a stack of similar bombs and detonating accident tally will usually just scatter the other bombs through blast effect. What can and does cause propagation – where other bombs detonate sympathetically – is fragments from the first bomb striking the cases of other bombs with great velocity.

In the early war Bomb Store the Fuzing Point Sheds were set slightly below ground level (as Swinderby’s is) to give extra protection and enable reduced traverse height. Later versions were ground level with higher ETs. But, it all depended on available safety distance. Regulations prescribed minimum safety distances between other buildings in the bomb store and also to the nearest service (RAF) and civilian occupied buildings.

Photo showing the earth traverses at the vandalised North End

Accidents were rare due to safety practices and usually involved faulty bombs or anti-handling bomb pistols during fuzing.

There were three standards of airfield bomb store built by the RAF, the pre-war 1936/37, the 1940 early war version Type C (which this version of Swinderby’s is sited on) and the 1942 version Type D. Swinderby had both. The Type C layout was inefficient when trying to support two or three operational squadrons requiring much double handling of receipts and issues and returns. When the airfield was upgraded to Class A standard with three hard runways, a supplementary Bomb Store to the 1942 standard was built in the south but now obliterated by post-war gravel pits and artificial lakes.

Scores of other airfields that had pre-war or 1940 standard bomb stores were given supplementary 1942 bomb stores. Where possible these were built next to – and connected to – the original bomb store but, where space was unavailable, in a separate location.

The bombs as brought from the store had transit fittings to protect the base and (in some types) provide a parallel rolling surface. The transit fitting were removed with bombs on the trolley.

Next, the bombs were ‘fuzed’ according to instructions from the Operations Room. Each bomb could be ‘fuzed’ in the nose only, tail only or both nose and tail. There was a bewildering array of Pistols and Fuzes to give instantaneous or delay detonation and even long delay. A Pistol was a purely mechanical item with no explosives and had to be used with a separate detonator. A Fuze contained a small amount of explosive and did not require a separate detonator. Fuzes were used mostly for air burst.

After the bombs were ‘fuzed’ the separate Tail Unit was installed and safety wires from the Pistol or Fuze led out through a grommet. The bomb train was then towed to the aircraft on dispersal for the ‘bombing up’ crews to load.

HE Bombs were just part of the load. Incendiary bombs were formed the greater part. Then there were Flares, Mines, Torpedoes, Pyrotechnics, Ammunition for guns. The bomb stores also kept Ground Defence items such as Grenades, Mortar Bombs etc. When a bomb store was to be ‘sited’ the designers took into account the terrain of the area and slotted the structures in locations where they could take advantage of natural screening features. The road had to be kept as level as possible with minimum gradients due to the tractor/trolley load involved. It is likely that Swinderby’s FP became semi-underground because soil was cut away to maintain the road level. (See below)

Photo showing original floor surface

The road systems were almost always single lane and a ONE WAY system enforced. The bends and corners were limited to a minimum radius to allow bomb trains easy passage. A single lane reduced the amount of materials required and speeded up the construction. FPs were usually built on a parallel loop road to allow through traffic to pass.

Remains of original loop road system

Please respect that this is private land, and no public access is allowed.

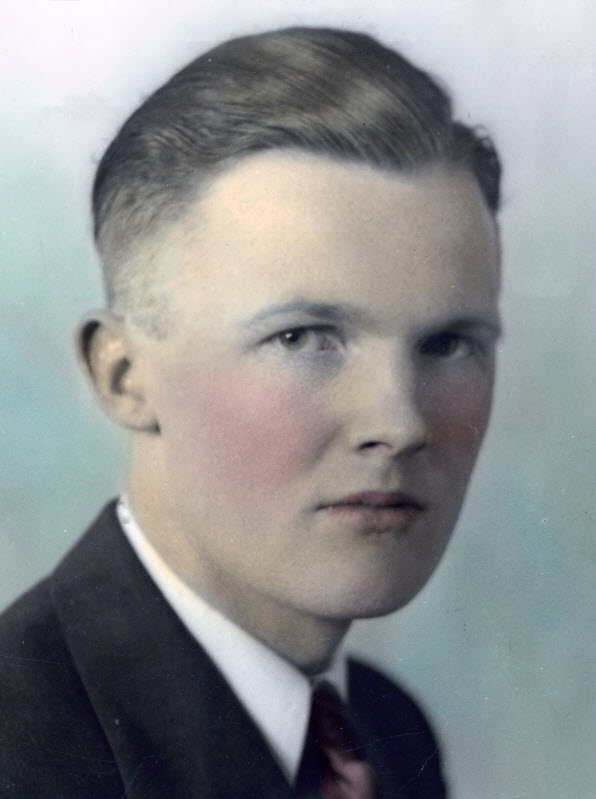

He was a Pilot flying Fairey Battles with 12 Squadron . On the 12th May 1940 he was on a daytime operation to take out a bridge over the Albert Canal, in Belgium. The mission was extremely risky and the Squadron lost all but one of the 5 Fairey Battles taking part. His aircraft was shot down close to the target which was heavily defended both with Anti Aircraft Guns and German Fighter planes. He was only 21 when he was killed. He and his Observer, Sgt Thomas Gray, were posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for their bravery. Please see the citation below.

He was a Pilot flying Fairey Battles with 12 Squadron . On the 12th May 1940 he was on a daytime operation to take out a bridge over the Albert Canal, in Belgium. The mission was extremely risky and the Squadron lost all but one of the 5 Fairey Battles taking part. His aircraft was shot down close to the target which was heavily defended both with Anti Aircraft Guns and German Fighter planes. He was only 21 when he was killed. He and his Observer, Sgt Thomas Gray, were posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for their bravery. Please see the citation below.

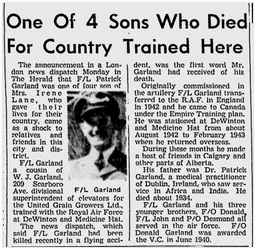

F/O Leslie Valentine CdeG

F/O Leslie Valentine CdeG Boston IIIA E-Easy

Boston IIIA E-Easy

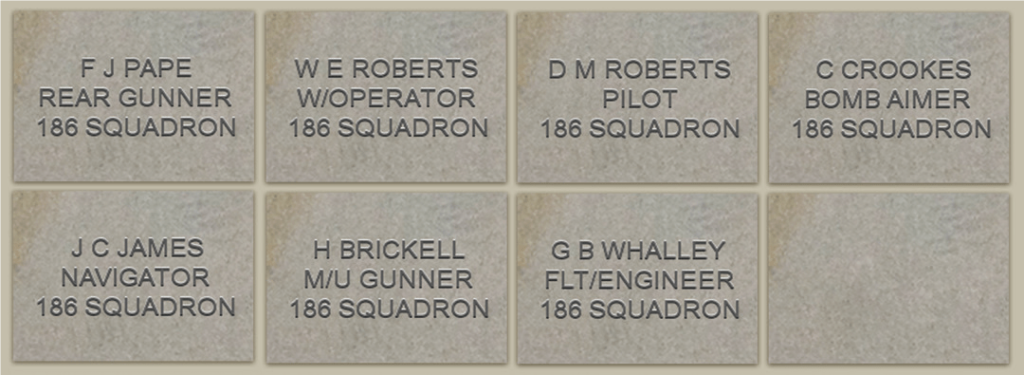

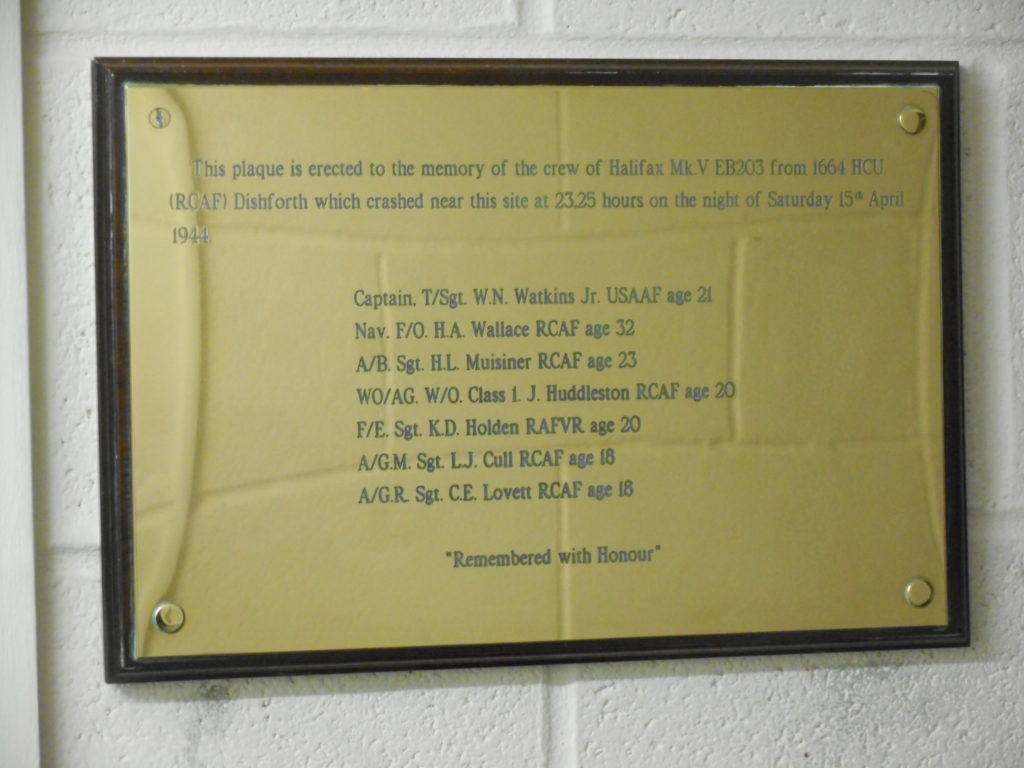

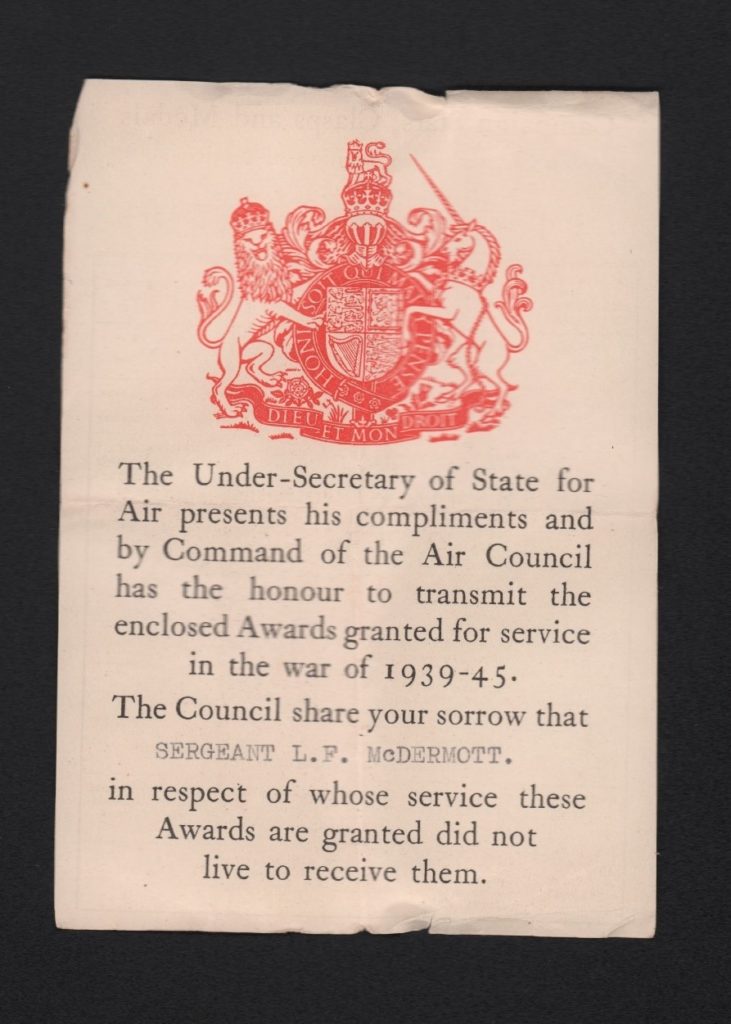

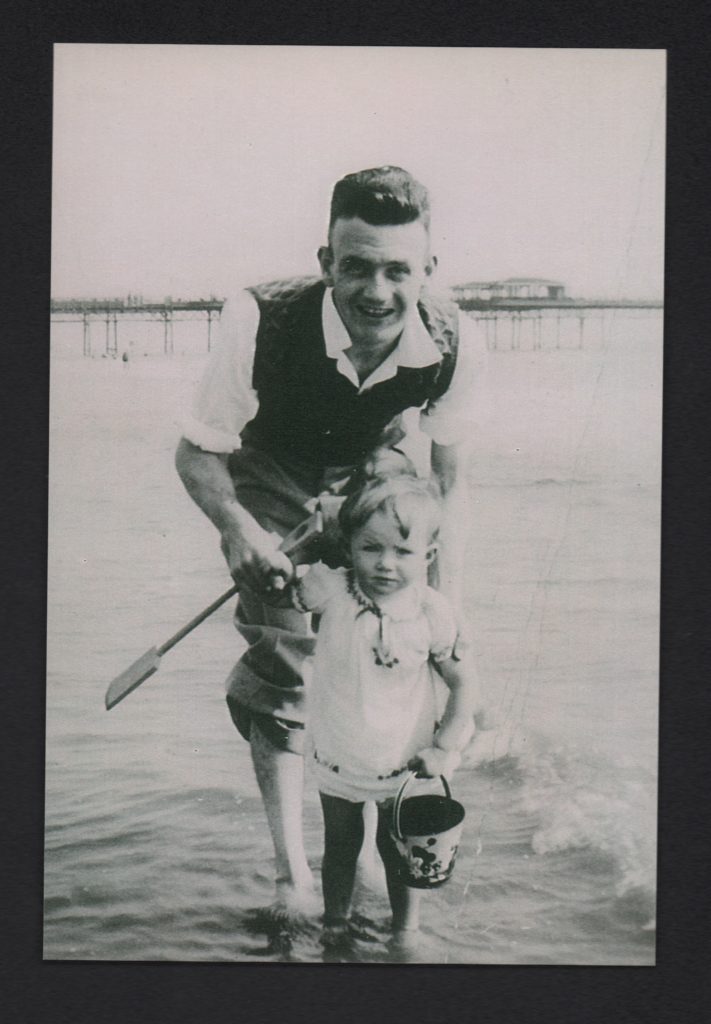

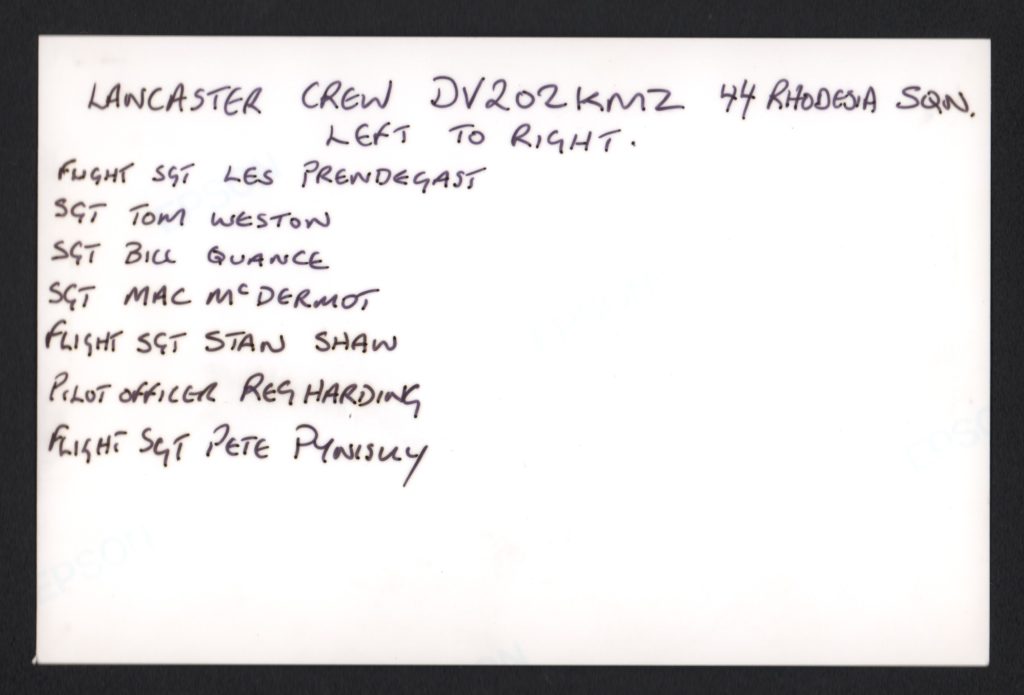

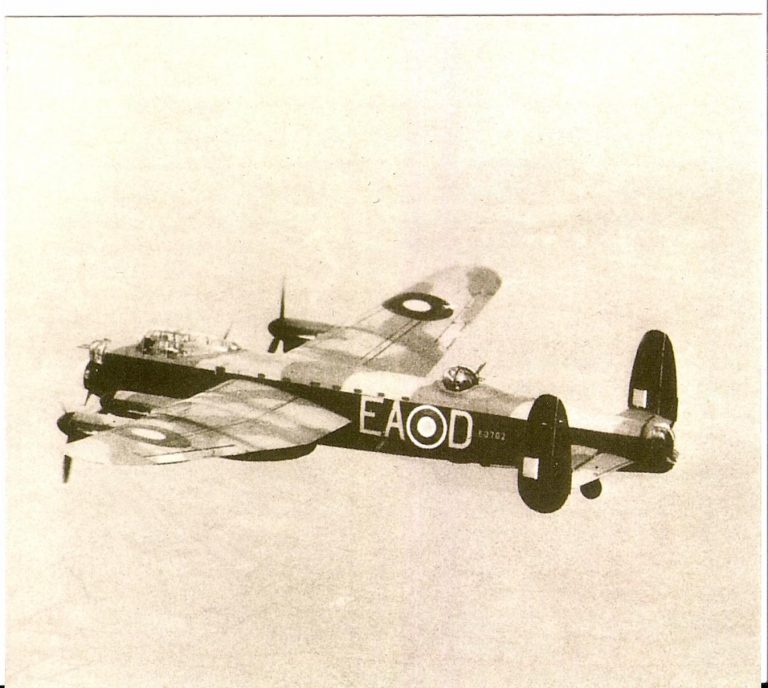

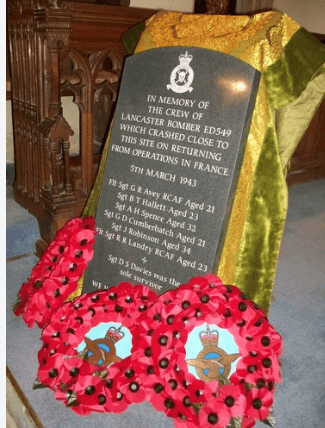

Their bombing raids were mainly in daytime over Germany to Kamen, Cologne, Dortmund, Datteln, Munster and Hamm. Their only night time raid was on the Friday 13 April 1945 to Kiel, and it was this mission on the return journey home where our crew all lost their lives, just as they were about to land back at base. Sadly, two Lancasters (YPB 488 and YPB 483) were called in to land at the same time – resulting in a fatal crash in the early hours of the 14th April 1945.

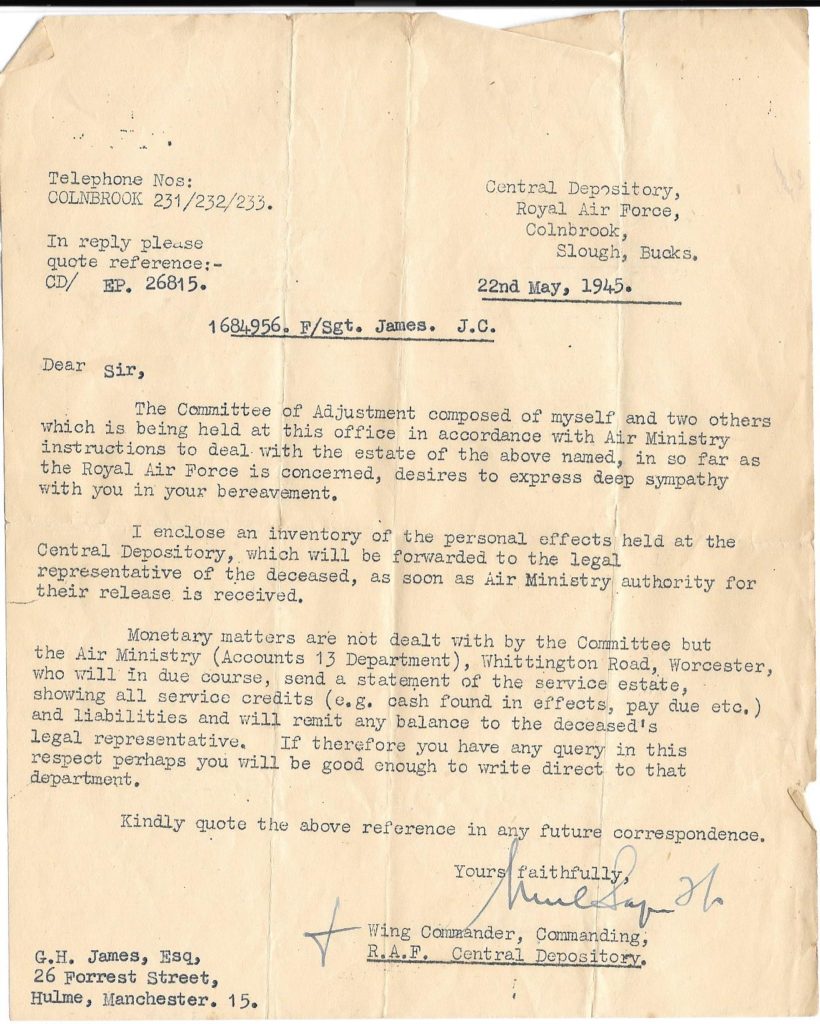

Their bombing raids were mainly in daytime over Germany to Kamen, Cologne, Dortmund, Datteln, Munster and Hamm. Their only night time raid was on the Friday 13 April 1945 to Kiel, and it was this mission on the return journey home where our crew all lost their lives, just as they were about to land back at base. Sadly, two Lancasters (YPB 488 and YPB 483) were called in to land at the same time – resulting in a fatal crash in the early hours of the 14th April 1945.