A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A REAR GUNNER – FRIDAY 23 FEB 1945.

0700 Hrs: With a quiet knock on my door, Jimmy our batman, entered with the ever welcome morning cuppa. It was his usual strong brew guaranteed to sustain body and soul against the penetrating chill of the North Lincolnshire weather. After a quick wash and shave I decided that yesterday’s shirt would pass muster for another day and at 0730, after my skipper’s stentorian call of “Ready”, from his room next door, we were off on the brisk half mile walk to the mess for breakfast. As always I devoured all placed before me; porridge, bacon, egg, sausage and fried bread followed by toast, marmalade and lashings of hot sweet tea. Even in my 21st year I was still a growing boy, fit as a butcher’s dog and doing my utmost to remain so.

0820 Hrs: Out again into the Lincolnshire weather arriving at the Squadron Gunnery Section to be briefed on the projected activities for the day by the Gunnery leader Flight Lieutenant ‘Johnny’ Wymark, DSO, DFC and to assist him with the administration duties of the section; this included a visit to the Squadron armoury. On 103 Squadron each crew had their own set of eight .303 Brownings and each gunner was required to carry out mandatory checks to maintain the guns in sound working condition. A register was kept of every gunner’s visit to the armoury by a tiny Geordie W.A.A.F. Corporal who ruled her domain with a rod of iron and wept buckets for every gunner lost on operations. Sadly I cannot bring her name to mind but I will never forget that small figure at the end of the runway waving to all the crews at take-off time and even the worst weather never deterred that small dark-haired girl.

1000 hrs: With the crew minus the skipper (A Flight Commander) and Bill Treen, the other gunner who was away on a course, we strolled down to the `Red Shield’ canteen for the morning break. As always this large room was packed with about 90% of the station aircrew establishment and a fair number of ground crew. The ritual of gathering at the Red Shield was threefold: a cuppa, a natter and to keep an eye on the two Post Office telephone kiosks outside the station guardroom. This was an early warning of impending operations; if service policemen emerged from the guardroom, and with a wee touch of the ceremonial the kiosks were duly padlocked, it was certain that an operation was scheduled. From that point in time all telephone calls in and out of the station were restricted to operations only and I think that remained so until two hours after the last aircraft was airborne.

I vividly recall that crews reacted in two distinct ways, some jumped up immediately leaving unfinished drinks, hurrying away to their respective sections whilst the remainder continued to linger over their drinks as if reluctant to leave the illusionary protection of the ‘Red Shield’. But eventually the canteen emptied leaving the dedicated staff of Salvation Army personnel who provided a welcome meeting place for aircrew and ground crews alike.

1100 Hrs: The ‘Battle Order’ is posted, our crew are down to fly as it seems to be a maximum effort for the Squadron, it is likely to be our first ‘Main Force’ target. It is an important day for me and although nothing had ever been said I think it was an important day for the crew as a whole. I had flown with another crew on a minelaying operation to Heligoland Bight on the 5th February, replacing Shorty Jay, a Canadian gunner who had lost a leg on an operation a few days before. Sadly that crew, skippered by Canadian Flying Officer Stephanoff did not return from an operation over Germany. Could this be the trip that we as a crew could prove with our new navigator and become fully operational with a main force target under our belts?

With Bill Treen away, I had recommended to my Skipper that Sergeant Walford, from Flight Lieutenant Anderson’s crew, would take over as Mid-upper and I would man the rear turret. I had known him from our first day in the Royal Air Force meeting him at Lords cricket ground where we had first reported as aircrew cadets. A farmer’s boy from Gloucestershire, he was legendary amongst our contemporaries in the gunnery world as an outstanding shot and in my opinion he was both conscientious and reliable.

We made our way to the armoury to check the guns, give them a pull through with 4 x 2 to ensure dry barrels then much to the embarrassment of our little Geordie W.A.A.F. Corporal, we ceremoniously placed the thick issue contraceptives over the muzzle flash of each gun to keep out the unwanted moisture which was quick to freeze in the cold hostile environment over Germany.

1145 Hrs: Back to the Section, a quick check to confirm that all gunners designated on the ‘Battle Order’ were available, and then into the Skipper’s office to report on our activities in the Armoury. He informed me that transport was laid on to take the crew to our aircraft ‘ITEM’ at 1400 hrs for pre-flight checks, and to install the guns in front, mid-upper and rear turrets.

Then a walk back to the mess to check on the daily tease of ‘Jane’, the famous strip cartoon of the era. The skipper suggested a relaxing game of snooker, and on this occasion I believe I managed to beat him. I think the menu that day was brown Windsor soup, liver and bacon, potatoes, and carrots, followed by Bakewell tart and custard. I calculated that during my wartime service I consumed about 90 gallons of custard annually, custard being one of the great fillers used by catering officers to satisfy hungry young men.

1400 Hrs: We loaded our eight Brownings onto a 15 cwt. of ancient vintage, climbed aboard and set off along the peri-track to our aircraft’s dispersal. On arrival, we off loaded each of us to our individual tasks and when all was completed as a crew we checked the intercom each in turn reporting to the skipper his position serviceable. Immediately the last report had been received the skipper initiated one of the many practice emergency drills. He always insisted on the highest standards and continued the drills until we performed them to his satisfaction. At last he was satisfied and he clambered out to have a word with our crew chief while we had a quick chat with the rest of the ground crew.

My next visit was to the PT section to see Flight Sergeant Frank Marsh the captain of our football team. Frank, a physical training instructor had been one of the famous five in Bolton Wanderers forward line that had promised to do great things in the English First Division 1939/40 season, alas they were together for just a few games when the war intervened. He became my great friend and gave me a tremendous amount of support and assistance in carrying out my ancillary duty as Station Football Officer. We were due to play a game in Scunthorpe the following day.

1630 Hrs: The crew meet outside Squadron H.Q. and we make our way to the briefing room situated in the Station Intelligence complex. An air of tension mixed in the smoke laden dim atmosphere when at precisely 1645 Hrs the Station Commander and the Squadron Commander entered, we sprang to attention and remained in that stiff posture until they reached their positions of the stage when he said, “Gentlemen be seated”. As he waited for us to settle down, this tall dark severe looking man glanced around the dim room with flashing eyes which seemed to convey encouragement and at the same time wishing that he was going on the operation. At last when the room fell silent he started to speak, “Tonight gentlemen you are privileged to strike deep into the heart of Germany; your target has never been attacked in strength before and although you will be part of a comparatively small force, I am confident you will destroy your objective in tonight’s attack. Your target is Pforzheim – hit hard and good luck”.

Then each Leader in turn, crossed the ’t’s and dotted the `i’s. My boss Johnny Wymark stressed the danger of relaxing when joining the circuit on return – the Luftwaffe were using JU88s in the intruder role, pouncing on unsuspecting victims coming in to land. As always, he ended with a reminder to all rear gunners to set the correct wing span on the Giro Gun Sight, to be aggressive, and with final “Good Luck!” the briefing was completed.

1730 Hrs: Our Night Flying Meal: bacon, sausage, egg, baked beans, chips, all washed down with a pint of milk. At 1830 Hrs. we assembled in the locker room, and the ritual of dressing up begins. Stripping down to my shreddies I don a pair of my girl friend’s discarded silk stockings, then aircrew issue silk/wool long johns, pair of everyday socks followed by electric socks. Next came my electric suit pressing in the sock connectors. Then shirt, battle-dress trousers, sea boot stockings with trousers tucked into fleece-lined flying boots, long thick aircrew sweater and battle-dress to;. all this before taking into consideration the Mae West life-jacket and parachute.

1930 Hrs: The last `fag’ is ground into the grass and we climb aboard. I slither down the slope to the rear turret, settle into my seat, plug in the intercom connection, connect the oxygen supply, turn around to pick up my gloves and then lock the sliding doors. I am now alone in my own little world. The intercom is live, and the skipper checks each crew position. I confirm I’m on full oxygen (gunners and pilot were on full oxygen from the ground, remainder of crew from 10,000 feet).

1935 Hrs: Start up time – Pilot and Flight Engineer commence the procedure, the four Merlins with their magical sound turn the metal airframe into a pulsating living machine, trembling like a maiden going out on her first date. The hydraulic system is now functioning, I unlock the turret turning the guns first to starboard then to port, then up and down – all is well and I return to the fore and aft position and relock the turret ready for take-off.

I next turn my attention to the task of gloving up. First the thin silk, then the electric (as always I struggle with the wrist connecting studs), then the RAF blue woollen gloves and finally leather gauntlets. I flex my fingers to check that my restricted digits will be able to perform their required tasks.

1940 Hrs: The wheel chocks are pulled away, brakes released and we start to roll. Eventually we reach the end of the runway, we turn starboard, line up, I place all four guns to ‘fire’ position. A ‘green’ from the caravan and our 66,000lb all up weight slowly gathers speed to free herself in her own wonderful way from Mother Earth.

As we settle down on the heading for Grantham, I unlock the turret and begin the 180 degree square search pattern which is to be my task for the next eight hours. As we climbed ever upwards through thin layers of broken cloud I can feel butterflies in my stomach. This feeling of apprehension was with me for the first and last 30 minutes of every operational flight. It was during this time I made peace with my God and I was at peace with myself and the rest of the world until 30 minutes before touch-down.

We soon crossed over the continental coastline, and as we were in the third wave of the attacking force we were right at the end of the Bomber stream, I saw few of our aircraft throughout the whole flight. At last we attain our operational height, and we press on towards unsuspecting Pforzheim, where even in homes and small workshops the Germans were manufacturing intricate time fuses, aircraft instrumentation, and parts for high technology weapons such as the `V’ weapons.

2230 Hrs: Suddenly, I feel a burning sensation on my right foot and ankle, I quickly switch off the power supply to my electric suit, the pain subsides and I estimate I will be without the warmth of my flying suit for the next five hours. I assured the skipper I can cope, but didn’t tell him my biggest worry was would I be able to play football the following day.

The skipper announces over the intercom “Target Dead Ahead.” The RT is tuned to the Master Bomber frequency, and I hear his call sign `King Cole’ calmly instructing the Main Force to use particular coloured target indicators for their aiming points as if he were officiating at a fireworks display. We were about 15 minutes away from our `bombs away’ time, and our bomb aimer made his way to his position preparing for his part in the drama unfolding over Pforzheim.

While this was going on, I had changed my wing span selections on the giro gun sight to 40 feet. The target area is FW190 and ME109 country, and I continue the never-ending search. Almost immediately, there is a movement on the starboard quarter, slightly higher than ourselves, about 800 yards range – it is a FW190 stalking us – he maintains his position and range. I calmly report to the skipper he replies “Roger” and I continued to report. The Mid Upper gunner confirms the sighting and swings his turret to port just in case they are hunting as a pair.

As we commence our bombing run, the 190 maintains his position and range and I begin to wonder if in fact he has spotted us. I can’t believe he hasn’t as we must stand out against all the glow of the target ahead. It flashes through my mind that when fired on German pilots are discouraged and usually leave wide awake crews to search for less vigilant ones. He starts to close the range without committing himself. I alert the skipper to prepare to Corkscrew Starboard remembering Johnny Wymark’s brief to be aggressive; I decide to open fire at 400 yards if he has not committed himself to a curve of pursuit attack. The Skipper concurs and I let loose with two short sharp burst of about three seconds each. A stream of tracer passes all around the enemy aircraft and a very startled fighter pilot immediately dives to port. He levels out low on our port quarter again at about 800 yards range.

I keep a beady eye on him then seconds later his starboard wing drops. He begins a curve of pursuit to layoff deflection for another target, I spot his prey low on our port beam, it’s another Lancaster and closing to 200 yards the 190 levelled off dead astern to give him a zero deflection shot – he loosed off a deadly stream of cannon shells into an unsuspecting prey. The Lancaster rolls over plunging down to Earth and to her doom. The 190 follows her down disappearing from my sight and I report the kill and our Navigator notes the time and position in his log.

The square search is resumed, our bombing run continues, left, left, steady, steady, when out of the blue the Master Bomber seems to be in trouble, in a clear undramatic voice he transmits. “This is King Cole I am handing over to King Cole 2”; he is unable to continue and his deputy takes over the task. Seconds later our Bomb Aimer calls over the intercom, “bombs away”, we have been successful in delivering our load. We have completed half our task and are on the way home.

0020 Hrs: Suddenly I begin to feel a cold chill on my behind, the excitement of the encounter with the 190 and the bombing run is beginning to wear off, I have been without the heat of my suit for nearly two hours and I am starting to feel the effects. It was a long uneventful return trip home and despite the butterflies in the last thirty minutes of the flight, I was elated when we turned onto finals and down through the funnel of airfield lights and ITEM kissed the tarmac with her wheels. Turning starboard off the runway I busied myself with selecting guns to safe, peeling off my gloves and turning off the oxygen supply as we taxied to dispersal.

As we rocked to a halt, the engines closed down creating an eerie silence. I began to unlock the guns from their mountings when one of our ground crew appeared at the open turret to assist in off loading the four Brownings. Disembarking at Squadron H.Q. the guns were conveyed to the armoury where the ever present W.A.A.F. Geordie Corporal volunteered to clean my guns whilst I went to debriefing. I accepted with grateful thanks and we made our way to Intelligence Section.

The skipper had a quick word with Doc Henderson who immediately steered me to the temporary canteen – poured a double rum into a mug and ordered me to drink as prescribed – right down, chug a lug style. The thick dark liquid flowed down my gullet and I felt the warmth spreading through my digestive system. As soon as I had finished drinking this we sat down at the table with Flying Officer Buster Brown, our debriefing officer. I told him of our brush with the F.W. 190 – the Navigator gave the time and position of the downed Lancaster, our Bomb Aimer, painting a colourful picture of the target and the aiming point he used from the directions given by King Cole 1.

The skipper paid tribute to the activities of the Master Bomber and we were later to learn that he had not survived and had been awarded the Victoria Cross, the last to be awarded to Bomber Command in WW II. His crew must be very proud to have served with such a gallant officer. It has been said the Pforzheim was the most perfectly marked target of Bomber Command’s offensive. The force of 360 Lancasters destroyed 83% of the built up area of this unfortunate medieval town.

Our story told we departed to the locker room to change back into normal uniform and went to the mess for breakfast. As we entered the dining room a fair number of officers were exchanging accounts of their individual experiences and the chances for the crew we had lost that night.

0530 Hrs: Breakfast over, the skipper and I walked wearily back to our billet. I was extremely lucky that the Doc found no sign of frostbite, and after an inspection of my burns on toe and ankle I was given clearance to play football that afternoon. Drifting into a sound sleep about 0600 Hrs, I dreamed of performing heroic deeds as the station goalkeeper later that afternoon.

Aircraft: Lancaster BIII PM – I 103 Squadron – RAF Elsham Wolds 1 Group

From the diary of F/O W E Monteith

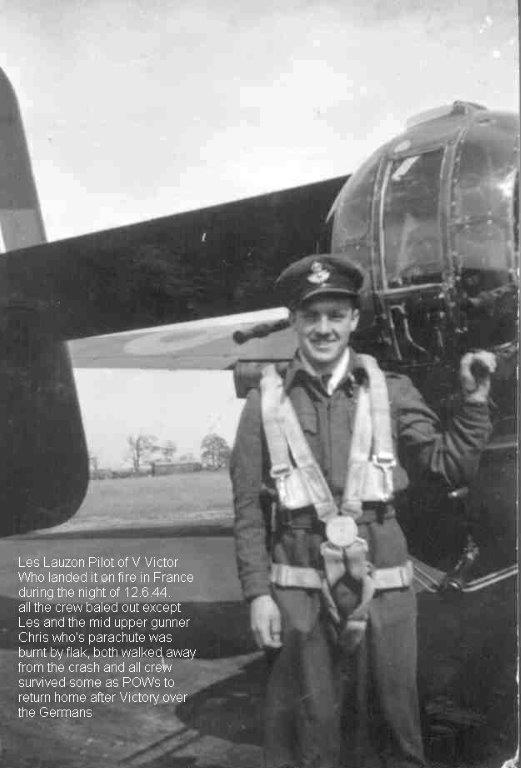

| Crew Left to Right: |

Standing: Wireless Operator W/O H.P. Cakebread RAF; Flight Engineer Sgt T. Urion RAF; Pilot S/Ldr K.J.R. Butler RAF; Rear Gunner and author of above account (in the shades!) Flying Officer WE. Monteith RAF. |

|

Kneeling: Navigator F/Sgt C. Cassier RCAF; Bomb Aimer F/Sgt Bonny Clark RAF; Mid-Upper Gunner Sgt V. Walford RAF. |

If you would like to see find out information of those who lost their lives on this raid, please click here

To help us preserve more heritage like this and to support the project please donate here