How the RAF Mountain Rescue Service began

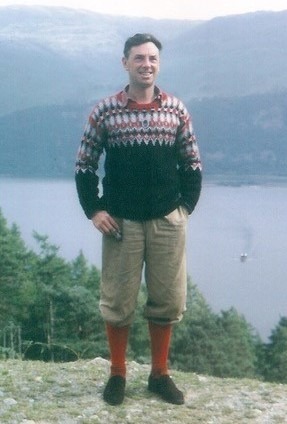

By Sergeant J. R. Lees 1927 – 2002 (N.C.O. i/c Mountain Rescue Team, RAF Valley)

Sergeant Johnnie Lees GM, who was well-known in civilian climbing circles in this country, was a member of the R.A.F Mountaineering Association’s Expedition to the Himalayas in the summer of 1955. Here he gives a brief outline of the development of the RAF’s mountain rescue teams, with special reference to those in North Wales written circa 1956 – Johnnie passed away in 2002

Early in the last war Royal Air Force stations near mountainous areas made their own arrangements for the organization of search parties and used whatever equipment was available. In North Wales there was one of these parties at RAF Llandwrog and it was here in 1942, that the Senior Medical Officer (SMO), Flight Lieutenant FW Graham, started training volunteers, drawn mainly from the station sick quarters. Later several vehicles, usually Jeeps and Humbers, were made available for mountain rescue.

Early in the last war Royal Air Force stations near mountainous areas made their own arrangements for the organization of search parties and used whatever equipment was available. In North Wales there was one of these parties at RAF Llandwrog and it was here in 1942, that the Senior Medical Officer (SMO), Flight Lieutenant FW Graham, started training volunteers, drawn mainly from the station sick quarters. Later several vehicles, usually Jeeps and Humbers, were made available for mountain rescue.

A Llandwrog diary, now at Valley, reads: “This log of the Mountain Rescue Service (MRS) vehicles was opened on July 6, 1943, on which date they were first used together fully equipped to attend an aircraft crash.” On that date a search exercise had begun at 04.45 hours on The Rivals (Yr Eifil, North Wales). Three hours later a message was received through the Humber Wireless and the walkie-talkies that an aircraft had crashed at Llangerniew; the mountain rescue team went there at top speed, but all the aircraft’s crew were dead.

Within a fortnight, however, the Llandwrog team had brought its first survivor in: he was an Oxford pilot who had belly-landed his aircraft at Tal y Cafn and he was picked up, shaken, from the nearby police station. A month later, after a four-and-a-half hour search, a crashed crew of five was found, relatively uninjured, 3,000 feet up on Foel Fras, in the Carneddau Mountains; they were evacuated safely. Before the end of 1943, by which time 33 survivors had been rescued from 22 crashes, the medical staff at the Headquarters of No. 25 Group and Flying Training Command had taken some interest and promised an increase in establishment of an N.C.O. nursing orderly and N.C.O. driver. At three other stations in the Command “rescue units” were formed and special equipment began to appear. Early in 1944 responsibility for the organization of the mountain rescue service was placed at Air Ministry level (Now MoD), where it rests today with the Director of Operations (M and Nav.) [Meteorology & Navigation?]

It also began to be appreciated in 1943 that proper nailed boots were required, that neither Wellington Boots nor standard RAF boots were of any use, and that a local shepherd’s advice on the direction of base from the top of Mynydd Perfedd, at night in a wet gale, could not be relied upon, whereas the compass could.

Snowstorm search

At midday on December 1, 1943, news was received at Llandwrog that an Anson had crashed on the Carneddau the previous evening and that two of the crew of four had walked to Bethesda police station. Apart from facial injuries they were unhurt, but could give no helpful information about the position of the crash. In snowstorms and poor visibility an extensive area was searched. Then, at 11.00 hours the following day, a third survivor arrived at Bethesda and, on interrogation, it seemed that Foel Grach was the most likely area of the crash. The search was continued and the fourth man was found, with a fractured foot, at 16.30 hours on December 2, sleeping, wrapped in parachutes, in the rear of the fuselage. On being offered rum by the M.O., he refused, saying that he “never touched the stuff”!

Early in 1944 a party of officers from Montrose visited the mountain rescue unit at Llandwrog to gather information to help start a similar unit in Scotland. And about this time a comparative trial between General Service (GS) stretchers and sledge stretchers, designed by Mr D. G. Duff, M.C., F.R.C.S., was made near Llyn Ogwen by medical representatives from Air Ministry, Flying Training Command, and members of the Llandwrog rescue team. The following April the team began a fortnight’s course of intensive training under a senior N.C.O. instructor from the 52nd Mountain Division. The course included navigation and elementary rock climbing, using ropes.

An unusual rescue – in a thunderstorm – was made one night in June, 1944, when a Llandwrog aircraft overshot and crashed in the sea a mile offshore. A dinghy was commandeered from an aircraft near the beach and the Medical Officer, (Flight Lieutenant Scudamore), the mountain rescue driver, and two other volunteers paddled in the direction of the crash. They met the five uninjured crew, already in a dinghy, and towed them back to the, by then, well lit shore, before the Air/Sea Rescue boat arrived from Fort Belan.

The girl who disappeared

Later that month came the first call out for a civilian in distress in the mountains. It was a girl and she was stranded on the cliffs of Cader Idris; local civilian climbers and police had been unable to rescue her. After some rock climbing Flight Lieutenant J. Lloyd and Corporal G. McTigue (later awarded a B.E.M. for his mountain rescue services) gained the ledge where she was reported to be trapped, only to find that she had gone; having been there for three hours, she had managed to extricate herself unaided.

The recovery of four bodies from the wreckage of an American C-47 transport aircraft found in November, 1944, over a week after it had crashed on Craig Dulyn, provided, the Llandwrog diary records, “the nearest approach to rock climbing of any crash so far … all wearing nailed boots … not a nice place for wellingtons and rubber soled boots”.

Flight Lieutenant Scudamore and the mountain rescue centre were, in June, 1945, posted to Llanbedr on the closing of R.A.F. Llandwrog. (In September, 1949, the North Wales team moved to Valley where it is based today.) With the war ended there was a rapid decline in the number of aircraft crashes in the mountains and, throughout 1946, the only break from weekly training exercises was in September, when a prisoner-of-war from Dolgelley, climbing on Cader Idris with a friend, fell and was killed. After an all-night search his body was recovered.

During the next three years the mountain rescue organization was extended. By 1949 there were nine teams covering Great Britain and Northern Ireland, each with a permanent staff of N.C.O. i/c, two drivers, a wireless operator and up to 30 part-time volunteers. And to each team a three ton load carrier was available – permanently loaded – in addition to two Humbers (signals and ambulance) and a Jeep or two. Mountain rescue sections had also become separate sections, with their own equipment, including a great deal for the part-time team members.

Wednesday afternoon exercises and evening lectures were instigated “to hasten the welding of a fully trained Mountain Rescue Team” Yet, it is probable that, at this stage, the mountaineering ability of the teams, never particularly high, had reached a new low.

Walkie-talkies and sleeping bags

As the teams gained in experience, new equipment was approved for their use – Commando jackets instead of gas capes, sleeping bags in lieu of blankets, type 46 walkie-talkies in place of the old 38s. But there was, as yet, no liaison between the few really skilled mountaineers in the Royal Air Force and the mountain rescue teams. As a result, the latter suffered and remained walkers who avoided steep places and who, through lack of mountaineering knowledge, found any slopes under snow dangerous.

A more enlightened attitude which brought about closer liaison with the mountaineers available in the R.A.F., through the Royal Air Force Mountaineering Association (RAFMA), resulted from several incidents. One was in the north of Scotland, where lack of experience in climbing in bad snow conditions defeated a team attempting to reach a crashed Lancaster on Beinn Eighe (3,309 feet). In an effort to prevent a repetition of this sort of thing the technical standard of training was raised with the introduction of biannual training courses – summer rock climbing and winter snow and ice climbing – with RAF Mountaineering Association instructors who taught one or two members of each team how to instruct in these aspects of mountaincraft. Some of the mountain rescue team officers and N.C.O.s attended these courses so that some degree of standardization in training resulted in better co-operation between teams.

Training rescue leaders

The post of Inspector of Mountain Rescue was established at Air Ministry, part-time, and Group Captain R. E. G. Brittain, who had some mountaineering experience, mainly in Asia, was appointed. He recommended the training of more expert S.N.C.Os i/c teams, to replace some of those who were filling the post of “sergeants of any trade”, and the P.T. branch was asked to provide volunteers. I had been a Physical Training Instructor (PTI) myself, and the first course began at Valley, under my instruction, in November 1952. By the time the training finished at Kinloss, with the winter course in February 1953, only three PTI pupils were left, out of the eight who started. Several more courses followed in 1954 and 1955, but then, as now, few P.T.Is can be found with the necessary interest and qualifications, so that the mountain rescue training situation is still not ideal.

Meanwhile, the assistant honorary secretary of the RAFMA, Mr M. Holton, was attached to Air Ministry A. D. Rescue (Air Ministry Assistant Director Rescue) to write a training manual for mountain rescue teams, which finally appeared as A.M.P. 299 in May, 1953. Thus ropes, ice axes, karabiners, and tricouni nails became familiar official terms and not just the mysterious names that the pioneer teams had heard other climbers talking knowledgeably about.

Because the civilian climbing fraternity has increased a hundredfold since the war and the number of aircraft mountain crashes has decreased, the position today is that teams are rarely called to an aircraft crash but are often asked for assistance at the scene of mountaineering accidents; this participation in civilian rescues has been approved by Air Ministry as good training.

Civilians expect too much

The higher technical standards introduced through training courses after the war and the competence of some of our Service climbers, especially Flight Lieutenants J. S. Berkeley and M. Mason and Flying Officer D. D. Stewart, who were already well known in civilian circles, led to a greater recognition of the teams by civilian mountaineers. Now the pendulum has gone a little too far and the younger generation of climbers often expects the still mainly part-time R.A.F. teams to be composed of ace climbers who are expert at whisking civilians, dead or injured, off inaccessible crags and faces while they sit back, watch – and sometimes criticize!

Group Captain Brittain’s successor, Squadron Leader D. Dattner, did a lot towards arresting these wrong ideas when, as Office i/c M.R.T, Kinloss, he addressed members of the Scottish Mountaineering Club at its annual meeting and dinner. More recently still Squadron Leader A. R. Gordon-Cumming, the present Inspector of Mountain rescue, has written an article on R.A.F mountain rescue teams in the quarterly journal of the British Mountaineering Council, Mountaineering, which would well bear reproduction in some of the other journals likely to be read by those who climb for a hobby.

The equipment still improves: once, three primus stoves, and a blanket each; now, petrol stoves with ovens, £16 (£338 in todays money) parkas, and sleeping bags. Thus the total value of personal equipment on loan to each volunteer is in the region of £60 (£1270 in todays money). The men who deserved this, the men who started it all in Llandwrog in 1943, must think the present day teams less hardy. Austrian ice axes and karabiners, nylon ropes, and Thomas sledge stretchers are all provided, and tests for an even better boot are still continuing.

Certainly, nowadays, aircrew who crash in mountainous country, either in Great Britain or in Cyprus, no matter what the time of year, may have every confidence in the mountain rescue teams ready to go to their aid.