The passage below has been transcribed from the dictated 2015 memories of Fred Perkins, aged 94.

Frederick William James Perkins

Leading AirCraftman (LAC) 1143173

Main Service: Fitter Armourer General, Liberator Bombers, Middle East Theatre.

Joined Full Time Service 23 May 1941

Began Overseas Service 13 August 1943

Ended Service 26 May 1946

Joining and Basic Training

I volunteered to join the Royal Air Force in February 1941. I went to Worcester to volunteer and I wanted to be an aircrewman. I was enrolled and sent up to Padgate, in Lancashire, to be tested for an aircrew roll. Straight off, I could see what I was up against for a place in aircrew training. Everyone else was from a university at a time when being a student meant you were the cream at the top, and I knew I didn’t stand a chance.

They accepted me into the RAF but put me on deferred service for aircrew. I got sent back into civi-street and I had a card that said I was in deferred service so I couldn’t be put into another branch of the military, but could get called up at any time to the RAF. Eventually I was called up and sent to a different airbase for training as an engineer, instead.

First Posting

I had my first proper posting down in RAF Christchurch, by Bournemouth (the airfield no longer exists). It was a radar research place, then, and they were experimenting on improving the radar system that had just been invented. I was assigned as general ground crew to part of the Telecommunications Flying Unit (Later the Radar Flying Unit).

It was civilian billets at that point, a couple of us in each house: one airman and one technician. They were quite big houses and they looked out over the sea. Being on the south coast, the beach and the bottom of the gardens were strung with thick barbed-wire in case of invasion by boat. On a Friday, I went to the Paymaster General, to collect the rent, twenty-four and sixpence for the week, bed and breakfast.

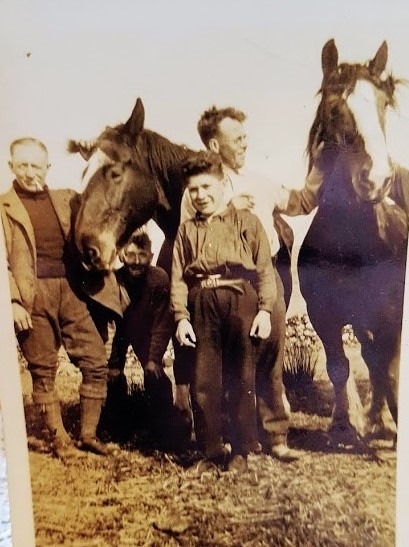

Often, in the morning, we would have to go out and round up the New Forest ponies that would wander onto the airstrip in the night. We had to get the tractor and move them off before the planes could take off.

One day, I was walking past the Flight Officer’s office, an old cricket pavilion, and he said to me “You wanted to be aircrew, didn’t you?” I said I did. He said “I’ve got just the job for you. Go down to the flight office and pick up a parachute, then go up to the end of the runway”. When I got to the end of the runway, not much more than a grass strip, there was an aircraft called a FaireyBattle. It was a lovely aircraft with a Rolls-Royce engine, and it was all metal. They were supposed to be a fighter-bomber but weren’t very good, so they were being used for training radar. It was perfect for radar testing as the metal body was great for screwing all these little di-pole reflectors into.

So I got in this thing, in the back as an observer and lookout, and off it took, the wing-tips wobbling as it went over the grass. We went out over the Channel and I was to look out for German fighters. In those days, the Germans were there, only twenty nine miles away in France. We flew out over the Channel, then came back in and they would test the radar detection zones with the aircraft to determine the distance and direction that the early warning system would work. We would go out into the Channel, come back in, then down towards the west coast and over Torquay, then come back to Christchurch.

As we came back in, the pilot said “How do you feel, you look a bit green?” I told him “I feel a bit green!” He told me to come back the next day, and sure enough we went up again, almost in the same area, then off towards Southampton to test that coverage. Southampton was an important area with all the docks. I felt a bit ill, then, with all the ducking and diving there, what with having to avoid all the barrage air balloons and the like.

I went up a number of times, as a look-out. When I wasn’t in the back of the FaireyBattle, I would work on the petrol bowsers. They carried a thousand gallons of high-octane petrol, with a fifty gallon oil tank dragged behind. I would fill up the aircraft fuel and make sure the engines and controls were well oiled.

I had a few days leave, then. When I came back, I asked if there was any chance of going up again in the ‘Battle. The Flight Officer said “You’ll be lucky, the aircraft was shot down over the Channel!” No-one knew what had happened, it had disappeared over the Channel, and that was it. They carried on the effort with several other planes, but I didn’t get to go up again.

We weren’t at Christchurch for that long. We built some dome huts to live in, moving out of civilian billets, and I remember one night playing cards in one of these huts. The Germans came along and dropped some bombs right down the back of us and I thought they’d hit us directly. The explosions blew out the candles and plunged us into darkness and I thought for a moment that I was dead. We had a lot of aircraft there: Beaufighters, Mosquitoes, FaireyBattles, others, all fitted up with radar and camouflaged with trees and nets. Parts of the airfield were hit, but the bombs missed all the planes, they didn’t touch any of them.

I nearly got hit several times. One night I went to the cinema and there was a raid. The Lyon’s Cafe, on the corner, got hit and when we came out of the shelter, the cafe wasn’t there anymore. Another time, I was cycling from Christchurch to the nearby airfield of Hurn. I heard the sirens go off, so I was peddling like mad, and all of a sudden I heard a swissssh. A line of bombs was dropped in front of me, in between Christchurch and Bournemouth.

Of course, now the Germans knew where we were. They knew we were developing radar in such a way, and that it was such an important technology. They knew where we were, and seeing as we were just the other side of the Channel to them, it was too dangerous to stay. We had to move.

We spent three days getting everything into the back of lorries, three dozen of them, and we moved up to Salisbury Plains. From there, we used the cover of darkness to go north. The lads in the back had no idea where we were going. We just piled into the back of some jeeps and followed the lead truck. Eventually, we arrived at Defford, in Worcestershire, just east of Malven. It was just fields of tall grass and broad beans, when we got there, and the sweet smell hit us as we got out of the jeeps. We had to get the farmer out to plough the fields before we could use them. After the planes had arrived, we built a better runway and we stayed there for some time. RAF Defford was born and we carried on with radar work. You can still see some of the radar dishes there, today.

One day, I was helping the top engineer with one of the fighters. He was having problems getting the oil pressure up in the engine and was revving the engine very high. The plane was jumping up and down with the vibrations until it jumped right over the chocks holding it in place. It started off down the runway with the engineer inside. It took him to the bottom of the runway to put the breaks on and get it stopped. We had to tow it back up the field with a truck, eventually, when everybody had finished laughing!

Full Time Fitter Training

After that, I was called up to Kirkham, in Lancashire (what is now HM Prison Kirkham) for a training course for fitters and armourers. The course would normally have run for several years, but was condensed down into about fourteen months for us. (Between 1939 and 1945 RAF Kirkham trained 72,000 British and allied service men and women. In November 1941 Kirkham became the main armament training centre for the RAF, with 21 different trades and 86 different courses on equipment and weapons varying from 22 riffles to 75mm guns.)

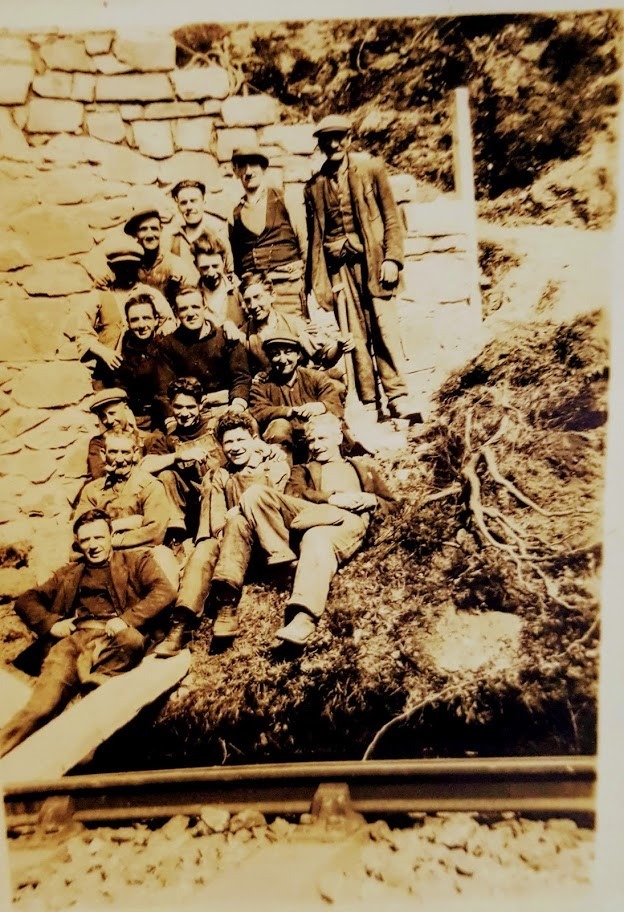

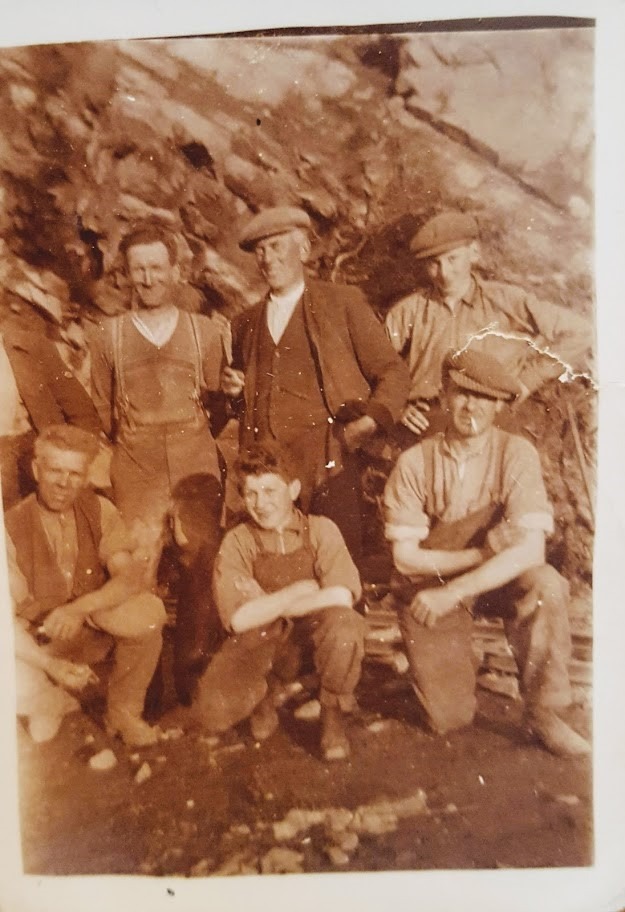

We were trained by Rolls Royce civilian trainers. There were about five hundred of us in a big hangar, twenty five in a row, each section with an instructor. The training was great, there was no better training than the RAF. I used to enjoy it, I was quite keen on the job.

We were trained in a number of different trades including blacksmithing, tinsmithing, coppersmithing, hydraulics, the lot. They took you from scratch. We had weeks of filing and grinding six-inch blocks of steel. You would file it flat, by hand, or make dove-joints, splits, rivets. Then you would start over on a new piece. The raw material would come on a tip-up truck and would be dumped in a pile for you to grab a piece when you needed it. It was easy to take a bit more of the metal off, but if you made a mistake and took too much off, you couldn’t put it back on, you’d have to start again!

We had the best tools, too. We had some lovely sets of tools, especially later when I was working on the Liberators. I had a big leather wallet with about twenty files in it: flat, smooth, round, square. We had to work with very fine tolerances, when we made or filed the work, because these things would end up as crucial parts of an airplane and if they failed, or didn’t fit properly, the plane could crash and the crew could die.

Right from the start, the trainer came over and said “That’s not the first time holding a hammer, is it? You seem to know what you’re doing.” I told him that I had come straight from making ceramic and steel fireplaces, on civi-street, so this was something I had been taught before.

We had lots of planes to train on, too. There were six big hangars at Kirkham. Six big hangars with full sized bombers, spitfires, hurricanes, and a night-fighter called a Boulton-Paul Defiant with a turret at the back and painted black.

About half-way through, the Adjutant called me into his office and said “You volunteered for aircrew when you joined.” I said “Yes, but they didn’t seem to be too eager at the time, there was no place for me on the aircrew course so they sent me to another squadron to be ground-crew.” The adjutant said “Well, there’s a place for you now.” I told him I wasn’t very interested now, I was training to be a fitter and was halfway through the course. He said “It’s not what you want, Perkins, it’s what the air force wants!” This was fair enough. They were keen, at that time, to get people onto the aircrew section because by that point, the Germans were shooting people out of the sky faster than we could train new men. However, because I had spent so long training to be an armourer, already, they had me finish my course.

By the end of the fourteen weeks training, I was a Special Armourer, as opposed to the basic Armourer I was to begin with, which meant that I could work on just about anything and put me into the top group. As soon as I was finished, I was put on the list to be called up for posting overseas.

Leaving Liverpool for the Middle East

As soon as my training was finished, I was to report to Liverpool, which was close to where I already was. On Sunday afternoon, we set off for Liverpool. When we got there the docks were full of all these big ships. We were headed for the Empress of Australia, a former cruise liner converted to a troop carrier. There were lots of men getting on her, very few were air force, most were army, marines and commandos. There were, I think, four thousand of us.

We set off at around 8pm in the evening, three or four tugs pulling us into the Mersey. By 9pm, the Navy dropped two depth charges because they thought there was a German submarine in the vicinity. We didn’t know what was happening. They dropped these depth charges and I thought we’d been hit by a torpedo! I thought “Oh well, we won’t be going any further.” But instead, the Captain throttled up to full power and we shot out of the area as quick as the ship could go.

Everyone was vaccinated, before we got onto the ship, and a few days later my elbow and arm swelled right up with vaccine fever. It took two days for the doctors to get to me, there were only a few on board and if you missed them on their round you had to wait until the next day. When they found me, they put me straight into the hospital quarters where I was waited on for a couple of days, which was lovely. Of course, when there were so many of us on the ship, finding a space for a hammock was very difficult. They were strung up everywhere with no space in between. If you weren’t there to keep a claim on your slot, like if you spend several days in the hospital, you lost your place.

We left British waters and went out into the Atlantic, where we sailed around for about a month. We had some ships on the left of us, some on the right, but we were waiting to make up a big convoy. I think we joined a Canadian convoy to make up the numbers. We eventually went down towards Gibraltar. There were, I think, two aircraft carriers, three destroyers, us, some others. About forty odd ships in the convoy as we went through the mouth into the Mediterranean. I think we were the first allied convoy to go through the Mediterranean. Before that, to get to Egypt, the ships had to go all the way round Africa.

We could see Gibraltar in the mist, with the Germans on the left, and we knew they had fast boats with torpedoes on them. We went through the strait on the North African side, down passed Benghazi. We spent about a week sailing along there because it was quite a way. I constantly thought we were going to get hammered as soon as the Germans realised we were there but we never saw more than a few German planes in the distance. It was a miracle, really. I heard the ships behind us, in later convoys, got hit, and I remember seeing a tanker in flames, on the horizon.

The thing that I remember the most, about going though the Med, was the heat and smell when we hit North Africa. From spending a month in the cold Atlantic, the heat that hit us, coming of Morocco, was like an oven. The smell was strong, too, like spices. Every country I have been in has its own smell. We were so close to the coast, following it all the way around, that you could see people walking on the beach.

Palestine and Egypt

We pulled into Port Said, at the mouth of the Suez Canal, on Sunday morning. We had to use pontoons to disembark and walk across to the land because the ship was so big it couldn’t get close enough to let us off. We all had two kit-bags and a Sten gun each. Of course, when we went across the pontoons it was a bit wobbly as there were so many troops getting off.

Most of the troops got off first and went along the Suez Canal. Thousands and thousands of them, marching twenty miles down the side of the Suez. We didn’t go that way, there were maybe fifty or sixty of us from the RAF and we went straight to Cairo. It was a Sunday afternoon, but for the people over there it was like a weekday. We drove up to Cairo airport and there was a transit camp for RAF personnel. We were posted, from there, all over the Middle East. It was just tents on sand and we were posted off individually as needed. I was there for two or three weeks.

I got to see the Pyramids, at that point. I went right inside with just a little wick candle to light the way. If you blew out the flame it was pitch black. Right inside, as far as you could go, I got. Right into the King’s Chamber. I also saw the small hole that went up to the sky and lined up with a certain star at a particular time of the year. I was able to go back, as well, in 1943.

About twenty of us were eventually sent off, by train, through the Sinai to Palestine. I was stationed at RAF Lydda (now Ben Gurion International Airport) in Tel Aviv. We stopped there in a small camp, just a tent village. It was a small airstrip to begin with, only small aircraft could use it, so the RAF built it up. We stripped out all of the orange trees, levelled the land and built a proper runway for the bombers. It was probably one of the first parts of the Middle East Bomber Command. We were attached to the Special Airborne division for a couple of months. At that point, we were sending off the bombers on bombing runs to attack the Germans.

I broke my leg in Palestine. It had been raining and the ground was very slippery, but we were playing football. I played a lot of football in the RAF, and a lot before too. We had some big games when I was overseas: it was something to entertain the men so it was very popular. I always played Inside Right for the RAF teams and on that day we were playing the Army. They were all tough as hell and just as rough. I got the ball and played it down the wing. I went to kick the ball across the pitch and these two army guys both tackled me and fell across my leg. I broke both the leg and the ligament. They just moved me to the side line and didn’t take me off anywhere else until the match had finished!

There weren’t any ambulances over there, so I was put in the back of a pick-up wagon. It felt like part of my leg was going in one direction, and the rest in another. They drove me to Nazareth to the make-shift hospital. It was a convent, converted for military use for injured servicemen in the Mediterranean. They fixed me up and plastered my leg. The next day, I thought my leg was itching. The hospital was riddled with bugs and they had gotten into my cast. I had to push them out with sticks and flush them out with water because they were eating my leg. A day later, they took us all out of the hospital, because of the infestation, and put us on a first-aid train. It was like a cattle-wagon full of stretchers. It was open-sided and I thought it would be chilly but as it was Palestine it was nice and warm. They brought us all cups of tea, bread, cheese and a pickle. The train took us to a huge hospital in the middle of Palestine, a huge place, full of all the wounded troops from all over the Middle East.

I had my leg in plaster for quite some time, so I was in a wheelchair for a bit. There was this one guy who said they had a cinema, so he took me off to see it. We had to go down a steep hill to get to the cinema. He was pushing me in the wheelchair and fell over as we were going down the hill. Off I went, bouncing down the hill and there was a ditch at the bottom of the hill. I hit the ditch, the chair went over and the wheel was spinning in the air – I can still see it now. All the others did was stand there, laughing their heads off!

After that, I joined the 5th Bomber Conversion Unit, working on Liberators. This eventually changed to the 1675 Heavy Conversion Unit and moved back down to RAF Abu Sueir, in Egypt, near to the Suez Canal. I was there for two and a half years. From that airfield, you could see ships going through the main canal. Most of the time it was the tops of the ships in the distance. We couldn’t see the water, just the dunes between us and them, so it looked like the ships were going through the sand.

I went swimming in the Suez, on more than one occasion. The last time I did was when I nearly drowned. My mate and I watched a big ship go by and waited for about five minutes before we went in, but it wasn’t long enough. I went in and the undercurrent from the ship’s wake dragged me under and pushed me down. I fought it but didn’t get anywhere and I didn’t think I would ever come back up. Luckily, I eventually got out of the current and made it back to the surface, but my lungs were burning like mad.

The Planes

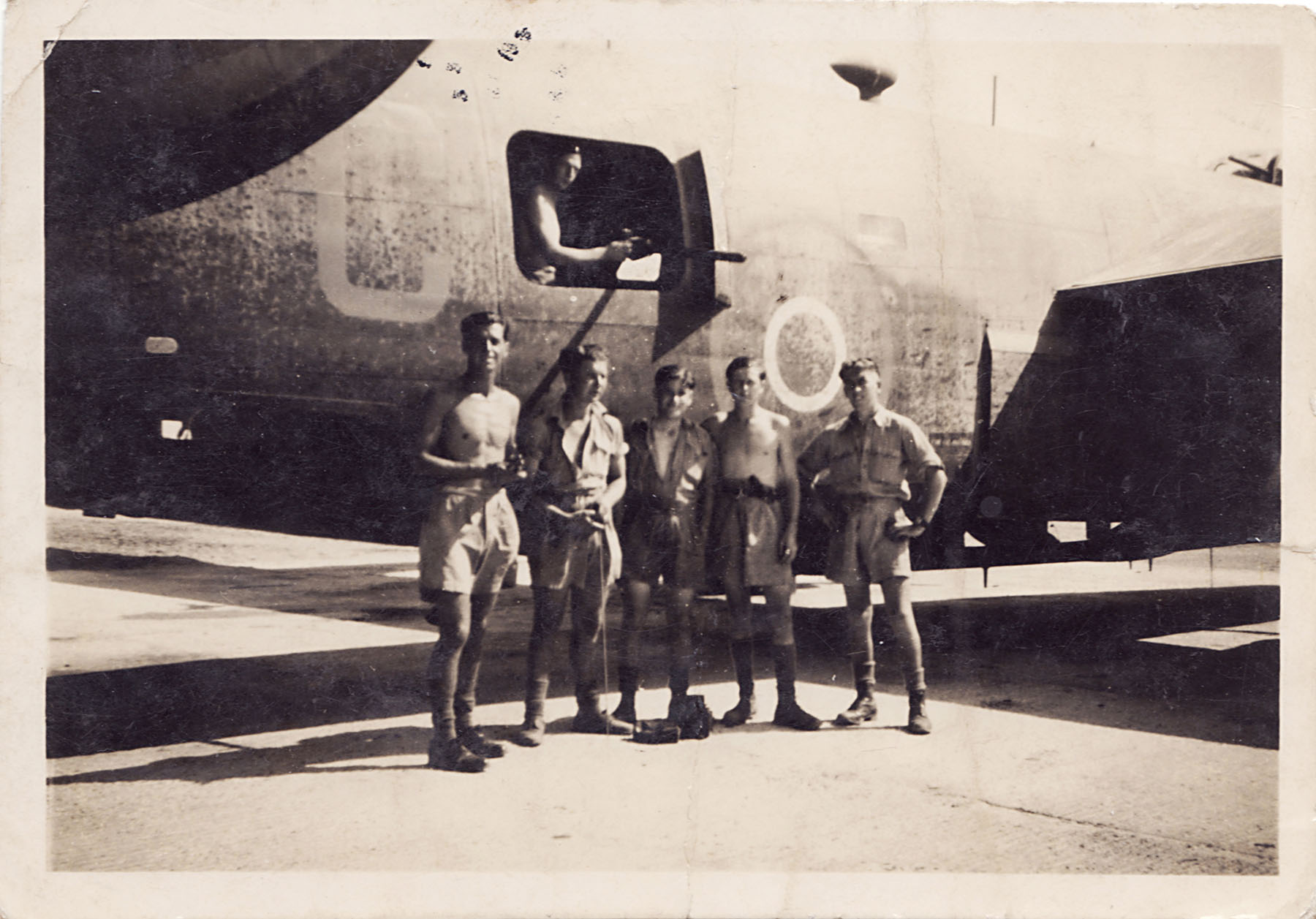

For most of my overseas time, I worked on Liberators (American B-24s). We had nine Liberators and six fighters: three spitfires and three hurricanes.

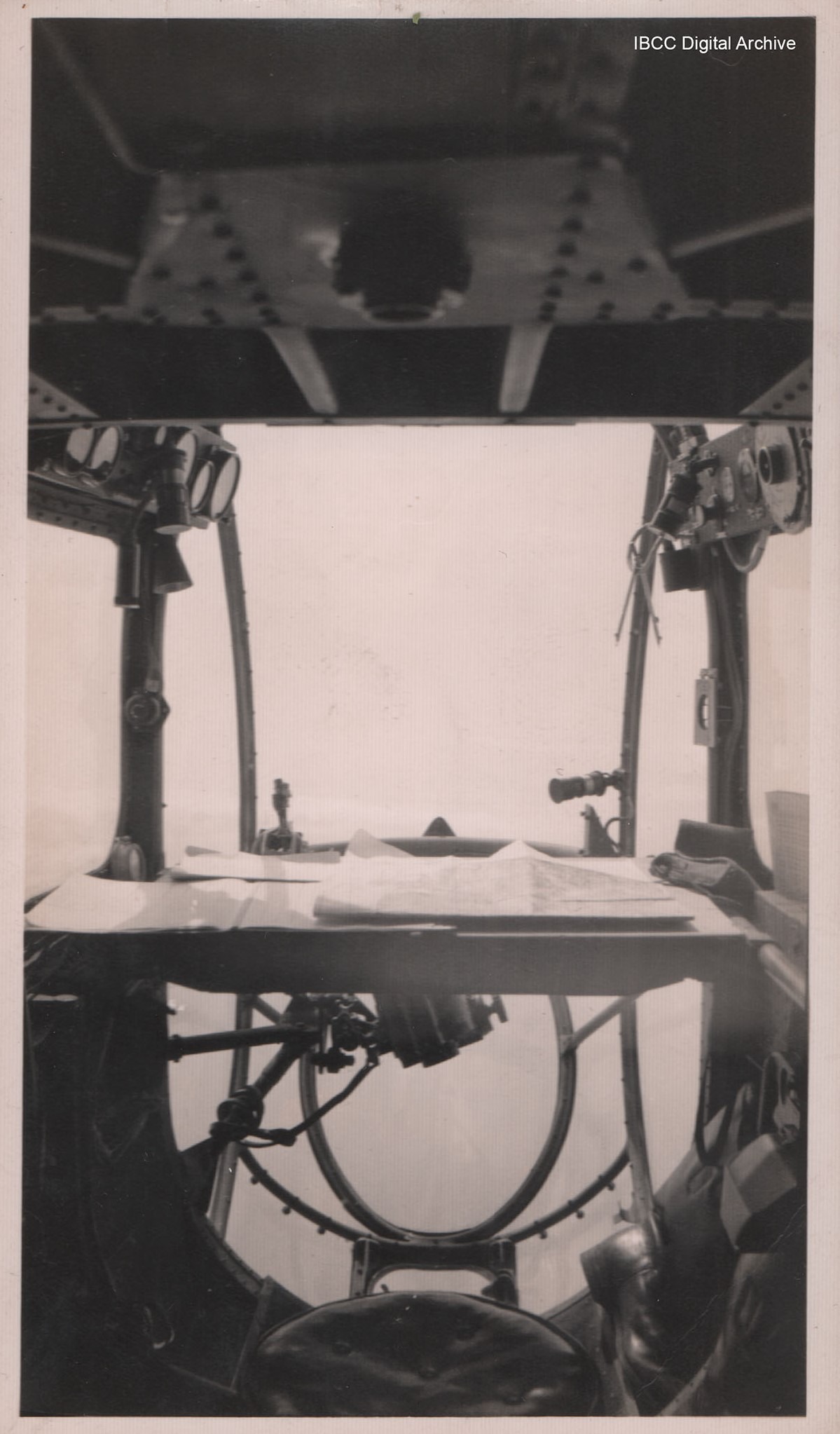

Liberators were my favourite. They had a good payload and were easy to get inside when you were ‘bombing up’ with the bomb trolley. They weren’t too far up in the air, so you could almost walk in and you pushed the bomb trolley right into the bay. You would put the swan-hook of the winch through the eye of the bomb and you would roll the winch up until the bomb sat in between the two saddles, one on each side. Then you would tighten the saddles on the bottom to keep the bombs steady when the plane was flying. After that, you would put in the detonators into what we called the pistol, at the back of the bomb. You’d put the arming vane into the pistol, followed by the safety pin. The vanes and pins would be kept in a box, fifty yards away from the plane, in case anything happened, and you‘d put the arming vanes into the bombs, to make them live, before the planes took off.

I remember one time, we had just finished ‘bombing up’ one side of a Liberator. Everything was in place, all ready to go, and a flight technician went into the aircraft to go through the checklist. He accidentally pulled the wrong lever and all the bombs suddenly fell out onto the ground. Of course, we ran in every direction to get away from the bombs. Not only could they have gone off if the safety pins came out, but they were damn heavy chunks of metal that would roll, as well. You could either get crushed or blown up. Or both. We shot off in every direction and didn’t stop until we were hundreds of meters away. Finally, the technician came out with a red face. I’ve never run so fast in my life! We were more angry, though, about having to sort it all out afterwards. It took us hours to check the bombs, make sure they were safe and then re-fit them. There was lots of sweating, swearing and blinding.

We kept the planes and bombs separate, most of the time. The planes were spaced out a long way apart, sometimes it was a fifteen mile round trip to fit all the planes, a mile or so there and back for each separate plane. They needed to be spaced in case there was a bombing raid on the airfield. You didn’t want all the planes and all the ammunition to go up in one lucky hit.

We had a big building, in Abu Sueir, that was just for the armoury. We had guns and ammunition and other such things stored there. A big brick place. I was in charge of the munitions and there were three or four guards posted there at all times. There was thick netting and wire, all the usual things, and the guards were supposed to patrol around the outside. I went there, early one mourning, with an officer to inspect the building. When we got there, there was this big hole in the wall, at the back, where all the guns and ammunition were kept. The guards were there, and I asked what was going on, but they just mumbled.

Someone’d stolen it all! They left about two or three camels and donkeys there. They had loaded all the guns and ammo they could carry on donkeys and stole off into the night. They must have been disturbed because they left a couple of animals. They’d broken through a double brick wall! They probably waited for an aircraft to come and then hammered like wild on the brick wall under cover of the noise of the aircraft engine.

The Liberators were very loud when they took off, they had four engines, and would go on lots of bombing runs over the Mediterranean countries. Sometimes they would drop saboteurs into Italy and Albania. The Liberators would go over in the middle of the night and drop these guys, they were SAS or similar, that type of person. When they did raids in Turkey, we would fit them up to drop leaflets over the enemy territory informing them we would be bombing there in twenty-four hours, giving the civilians time to clear out of the area.

For fun, sometimes we would add old crates of waste from the naafi. The crates would be wooden and would whistle when they were dropped, like bombs, and the enemy wouldn’t know if it was a bomb that hadn’t exploded.

We dropped supplies, too, all kinds of supplies. Medicines, ammunition and supplies for allied troops. We dropped a lot of medicine in all the areas. They had yellow parachutes on then so you could see them. Of course, the people would gather these parachutes and keep them. The local blankets and beds were rough as hell, so people would take the parachutes as they were nice smooth silk.

As a Special Armourer, I also worked on the guns. They were mainly .5’s (0.5 calibre, 12.7mm Browning Gun) which were a good gun. On the Liberator, you’d have probably about 6 stations where you had at least two .5 guns. They did away with the rear-turret’s upper guns because when they fired, the crew would have two guns firing each side of their ears, and they didn’t like that very much.

But, as I said, the Liberators were easy to work on. You had two side gunners, two .5’s in a side slot. The swivel range of these was limited with a cable. If the gunners were new or got a bit panicky, they could swing the gun round hard and break the cable or stretch it. We would have to reset the cable after each run. We’d get a guy with a long rod, stuck in the end of the barrel, to simulate where the bullets would go. The guy outside would walk around and we would clamp up the new cable inside to where we wanted the range of movement to be. You’d have to stop the range about six feet from something you didn’t want to hit because when you fire the guns, you get a cone of fire and had to build in some leeway. You also had to make sure that if the cable stretched again on the next flight, the gunner couldn’t shoot off the plan’s wing or tail if the cable allowed the gun to turn further than it should.

The Spitfire was another one we had to change the guns on. They had .303 guns, there were eight of them. A lot of the British planes had the 303’s, which were no good at all, they had no firepower, they were like pea-shooters. The Americans used all .5s, they were definitely a better firepower. With the fighters, you would put the plane on a trestle, in the flying position, and you had a target about five hundred and fifty feet in front. You had a periscope on the gun and you lined it up to the target so that all the bullets converged in the same place.

On occasion, we fitted a 20mm canon, one on each wing, but you had to have a little bit more of an anchorage if you did that on a Spitfire, because of the extra recoil. The 20mm had a special recoil-spring, a square spring. You had to have a special clamp to squash and compress it, as it was so strong to deal with the extra force of the canon when it fired. You’ve probably seen the canons in the old war films where the 20mm would strafe enemy trains.

There were different types of ammunition, too. You’d have armour piecing shells, but we never liked them because they would wear out the barrel on the canon. You’d have incendiary ones, normal shells, they were both fine. But we used the canons more on the Hurricanes because those planes were more substantial. So we used to like to put them there. The Hurricanes also had a bit more room to move about with. The Spitfires were cramped to mount the guns.

You had to be careful on the Spitfires, more than the Hurricanes, because the Spitfires used to catch fire. There was excess oil, sometimes, in the Spitfire exhaust cylinders, that could be left behind. So the flight mechanics would stand by with fire extinguishers in case the thing caught fire when it was started. The mechanic who was testing the plane would keep the engine going to blow out the flames because it was too late by that point to do anything else.

We had a lot of problems with the Spitfires, out in the desert, because they were so light and flimsy, compared to the Hurricanes. You’d see them land at the end of the runway and not come any further. When you got down to the end of the strip, the thing would be tipped up on its nose! The front end would be dug into the ground. It was too front heavy and easily caught gusts of wind. It caused no end of trouble for us and the pilots.

All sorts of things would happen, or go wrong, when I was out there in the Middle East. One bomber came back late, from a run over Greece. It finally came into view, coming from the Sinai towards us in Abu Sueir, over the Suez Canal. As it was nearing the end of the runway, there was this tremendous bang and the plane just blew up! We never found out what had happened. When we got to the site of the wreckage, it was all just burning fragments, too little to find anything else. It wasn’t like now with forensic teams to check every last millimetre.

On another occasion, a plane came in without the undercarriage down. It scrapped along the ground and everyone was okay, but the plane was a write-off. We had to winch it up, put it on a large lorry and take it off for spares.

We often had to clean out the planes, once they had returned from a bombing run. The aircrew would be trapped in these things for many hours and there was often waste that needed cleaning out. Some of the crew would get airsick and there would be vomit. Sometimes the Germans would attack the planes and shoot at them and if the plane was hit, there may be blood as well. What ever it was, we sluiced it all down with paraffin.

One time, a Liberator came back with fewer crew than it left with. The plane didn’t get into combat, but the rear gunner was missing. The hatch was open and the guy was gone. We thought he must have had enough and jumped out. It happened, sometimes, if someone decided they couldn’t take it anymore. Being an aircrewman could be very stressful and sometimes someone would just snap.

Local Wildlife

The difficulties of living out there were not limited to the aircraft. I went to a lot of places, but they all taught you to get used to varied, tough conditions. In one place there were four of us sleeping on a concrete hangar floor. Out in the desert, it was just sand and dust and tents. You had to check your bed, or hammock or what ever, for snakes before you got in for the night. Every morning, you‘d have to turn your boots upside down and hit them with a stick to get any scorpions out! You’d get bedbugs and things, the way we got rid of those was to thrown paraffin over the bed and blankets, then watch all these things come scurrying out. The paraffin evaporated off quickly in the desert.

I slept in the armoury, quite often. I remember having to turn the light on, at night, because the scorpions would come in under cover of darkness and run across the floor. The light would dazzle them and you could hit them with a stick.

I remember, as well, one night I was lying in a bed and a snake fell onto the mosquito net. I was in Palestine at the time and thought a terrorist had lobbed a grenade into the room. But I thought “If it is going to go off, it goes off, I’m not getting out of bed!” The next morning, the Palestinian guard came round, whilst I went off for breakfast, and he found the snake coiled up in the warmth of my blankets. When I came back, he’d already hit it with the butt of his rifle and laid this four foot snake out on the floor.

We’d get eaten alive by mosquitoes, too, quite often, especially in Abu Sueir. We would work at night, as often as not, refitting the bombers for an early morning raid. We’d work under arclight, the Sweetwater Canal ran right along the side of the aerodrome and the light would draw the mosquitos right to us.

There were bigger animal pests, too. There were a lot of stray dogs there, and they had a lot of diseases. Every Tuesday morning, early, I had to go around with a rifle and shoot any strays. On one particular day, I was doing my rounds and some wild dogs were running across the field. So I got my rifle and shot all three of them. When I got closer, to collect the bodies and burn them, I saw that one of the dogs was an alsatian. It was only then that I realised that only two of the dogs were wild, and they were chasing the alsatian. The alsatian was the pet of the Chief Engineer, and I had shot it, too. The Chief was okay about it, the dog should have been locked up and had gotten loose, but I still felt bad.

What ever the problems you dealt with them because you were all in it together. You had comrades. You didn’t fight amongst yourselves, the comradeship was so unique, you stuck together as a unit, you had a great temperament and it all blends in to those harsh conditions. You put your life in everyone else’s hands, so you trust them, you look after each other. It’s hard to understand when you are in another walk of life.

Iraq

When the European war ended, there was nothing left for us to do in Egypt, so I was allocated to another post and taken into the Navy Fleet Air Arm. I was sent to Basra, in Iraq: RAF Shaibah. There wasn’t much of anything there, before the RAF got there. It was built for the war. They were short on fitter-armourer generals. There were only five of us there. When you were a fitter general it meant that you could do everything. The work ranged right from the cameras that were fitted along side the guns for reconnaissance and records, to the fluid for the hydraulic systems that operated the turrets. You had to bleed and feed that fluid at different times of the day because it would expand and contract with the big temperature ranges you got in the desert.

I taught some of the local Iraqi army how to shoot. They had guns but they didn’t have any proper training on how to shoot correctly. Every Friday afternoon I would take these guys to the range and teach them how to sight up a gun, how to adjust the fore- and back-sights to correct the bias. The foresights would often take a bashing, being on the tip of the barrel, and the men would be rough with the guns and knock the irons. Teaching the Iraqis to keep the gun sights lined up meant the difference between being able to hit their targets and missing by miles.

One day, one of the recruits shot wide at something. The round ricocheted and hit a tractor in the fuel tank. There was a hell of a bang, a lot of shouting in different languages, and a tractor on its side, blown over by the explosion.

The Iraqis were friendly, but the Sudanese were a problem. We had an open-air cinema and we were all sitting round watching a film. There was a lot of banging going on and we thought it was the film. That was until someone shouted “Duck!” It was the Sudanese, driving around in the desert nearby, shooting off their rifles! Everyone was more annoyed with the disruption than with the threat of being shot!

Then the Japanese war ended and there was no more use for us at all.

Coming Home

I was in the RAF until my last posting in Iraq in 1946.

I remember leaving Shaibah in a Dakota transport plane, heading back to towards Egypt. We took off and the plane was overloaded with troops and gear. After a short while into the flight, there was a huge sandstorm right in front of us, thousands of feet high and tens of miles wide. We couldn’t get over the top as we were already overloaded, so the pilot tried to go through. I felt the pressure of the sand hit the plane, then there was a huge gust of wind and the plane went over on its side and scythed through the air, dropping like a stone. We were lucky we didn’t hit the deck and all get killed. I thought I’d been out there for four, five years, survived the whole war and nearly been wiped out on my way home!

Once I got to Egypt, I came back across the Mediterranean on a ship from Alexandria. It took a week to cross the sea to France, Toulon. I remember the harbour was absolutely packed with ships that had been sunk. (The French had scuttled their own fleet to prevent the Germans from getting their hands on them). The locals had very little to eat, at that point, and almost no bread. On our ship we had so much bread that it had gone stale by the time we arrived in Toulon and it was all thrown overboard into the sea. I don’t know why it wasn’t saved, but I remember loads of loaves of bread floating in the sea. When we got into port, you couldn’t buy even a biscuit!

We stayed in what was left of the German’s camp, there, for a week or so before heading to Calais. It was several days across France, by train, mostly at night. I remember it was a moon-lit night as we passed Paris and I could see the Eiffel Tower in the moonlight. I also remember taking a walk out into the fields, when we stopped for an hour at one point, just walking through the crops.

We finally crossed the Channel, back into Dover, at about ten at night. The next morning, I was de-mobbed in Stratford. I got my de-mob suit, a quick medical, my money and was out of the gate. As quick as that I was out of the Air force. Done.

When you come out of the service, you do feel a bit lost. You had a regimented life in the service, and they looked after you. The RAF looked after you really well, but when you leave, it’s all down to you. You have to completely adjust yourself. It’s probably harder to come out than it ever was going in. You had to work all times of the day. In the service, you are paid to work 24 hours a day and you work for 23 hours 59 minutes.

I wasn’t relieved to be out of the air force, to be honest. We travelled so much, spent so long in different countries, that I felt immune to much of the feelings of ‘home’. No matter where you went, you were the same person, you weren’t excited, you weren’t depressed, you just went with it. I never thought “Thank God I survived that” or “I made it through”. You had to be immune to all of that, if you wanted to keep your sanity. So much happens to you, and you are pushed and pulled in all directions that you just had to go with the flow. It was almost like brain-washing, in a good way. “Do as you are told, go where we tell you and you will be taken care of” was the feeling you got in the RAF. They looked after you, as much as they could. You never knew what the enemy was going to do, but you knew those around you had your back. If you didn’t keep that in mind, you would have gone mad.

I had about six weeks of leave stored up, when I was de-mobbed, at the end of which they called me and asked if I wanted to go back into the air force. I would have been sent back to Iraq but I’d already done several months over my time. Twice they asked me back, but by then I’d had enough. We all had.

For more Veterans’ Stories see our Blog Space here

The IBCC Digital Archive carries a wide range of preserved documents and interviews from this period. To find out more click here

Upon leaving the RAF, Gunner B came home to Kirkcaldy to re-join his wife, Nell and his baby girl Helen, named after her mother. Her Sister, Patricia (Trish) came along a little later and me a few years later still. He went on to have successful career as a Chief Engineer with the National Coal Board (Aye, doon the pits), Alexander’s Bus Garage, and finally Thomas Nicol Salvage in Kirkcaldy.

Upon leaving the RAF, Gunner B came home to Kirkcaldy to re-join his wife, Nell and his baby girl Helen, named after her mother. Her Sister, Patricia (Trish) came along a little later and me a few years later still. He went on to have successful career as a Chief Engineer with the National Coal Board (Aye, doon the pits), Alexander’s Bus Garage, and finally Thomas Nicol Salvage in Kirkcaldy.

Breaks throughout the night would have filled them up with porridge followed by bacon, egg, sausage and fried bread and chips. Maybe some toast, marmalade and a few cups of hot sweet tea and followed by a few cigarettes. A good chance for a blether and time to discuss any fears or faults that may have arisen.

Breaks throughout the night would have filled them up with porridge followed by bacon, egg, sausage and fried bread and chips. Maybe some toast, marmalade and a few cups of hot sweet tea and followed by a few cigarettes. A good chance for a blether and time to discuss any fears or faults that may have arisen.

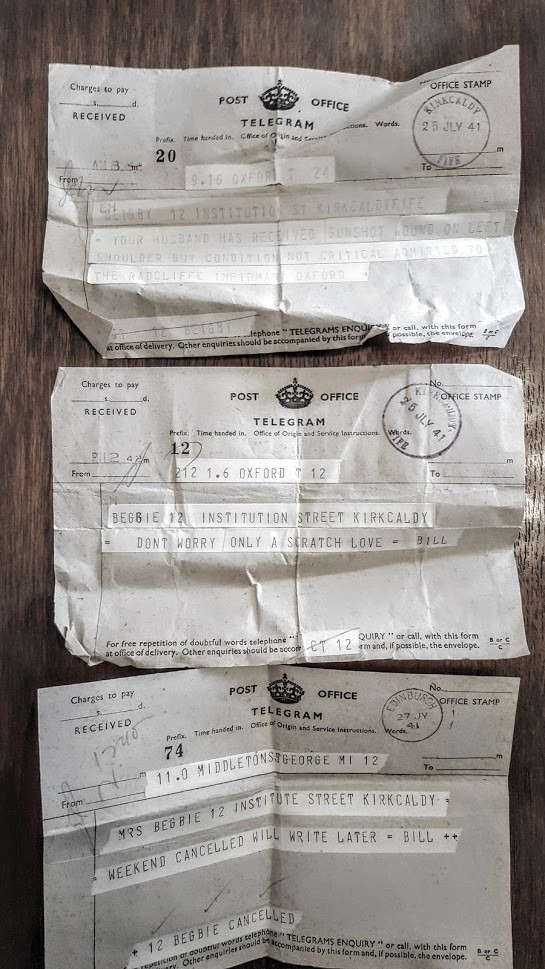

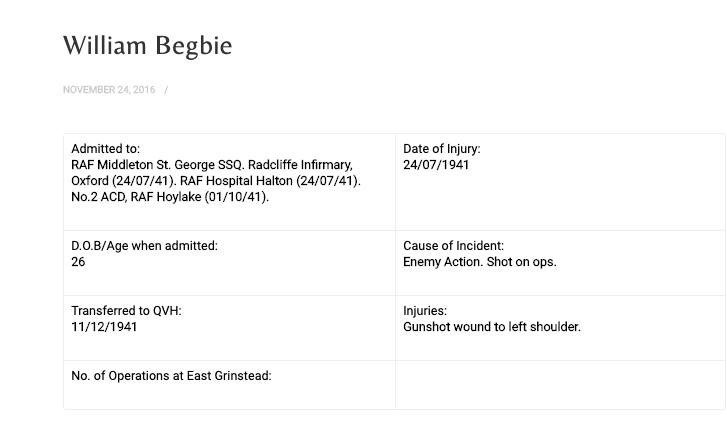

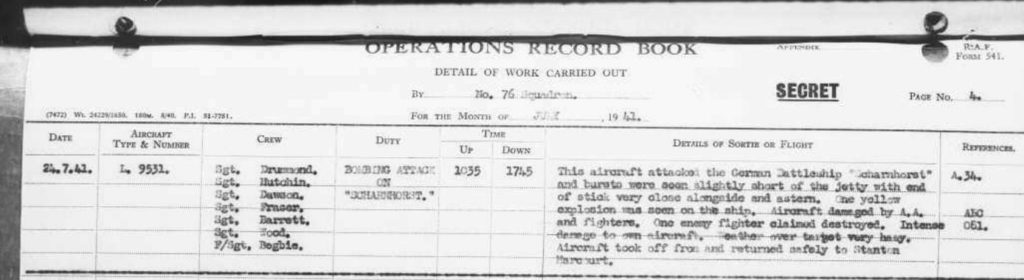

Now that the RAF knew that the Sharnhorst and Gneisenau were in La Rochelle moored to the jetty, there was a mad rush on. They needed to plan a bombing raid and quickly destroy them before they could leave La Rochelle. Apparently, there was 30,000 Canadian troops ready to sail from the other side of the Atlantic. Tensions were high in Bomber Command. If the Sharnhorst and Co were able to get out of La Rochelle and into the Atlantic….It was a hellish thought to entertain.

Now that the RAF knew that the Sharnhorst and Gneisenau were in La Rochelle moored to the jetty, there was a mad rush on. They needed to plan a bombing raid and quickly destroy them before they could leave La Rochelle. Apparently, there was 30,000 Canadian troops ready to sail from the other side of the Atlantic. Tensions were high in Bomber Command. If the Sharnhorst and Co were able to get out of La Rochelle and into the Atlantic….It was a hellish thought to entertain.

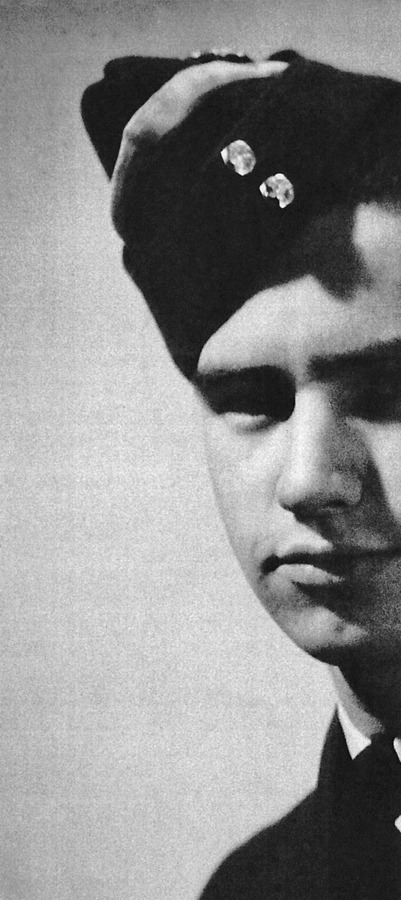

This is Jack with his mother, taken just before he went overseas.

This is Jack with his mother, taken just before he went overseas. “A rapid calculation by Tommy Melvin based on an estimate of present course, time and speed, indicated that we would need to alter course 120 degrees to port to reach England. This eventually turned out to be very accurate, considering that he had no charts or instruments to work with.”

“A rapid calculation by Tommy Melvin based on an estimate of present course, time and speed, indicated that we would need to alter course 120 degrees to port to reach England. This eventually turned out to be very accurate, considering that he had no charts or instruments to work with.”