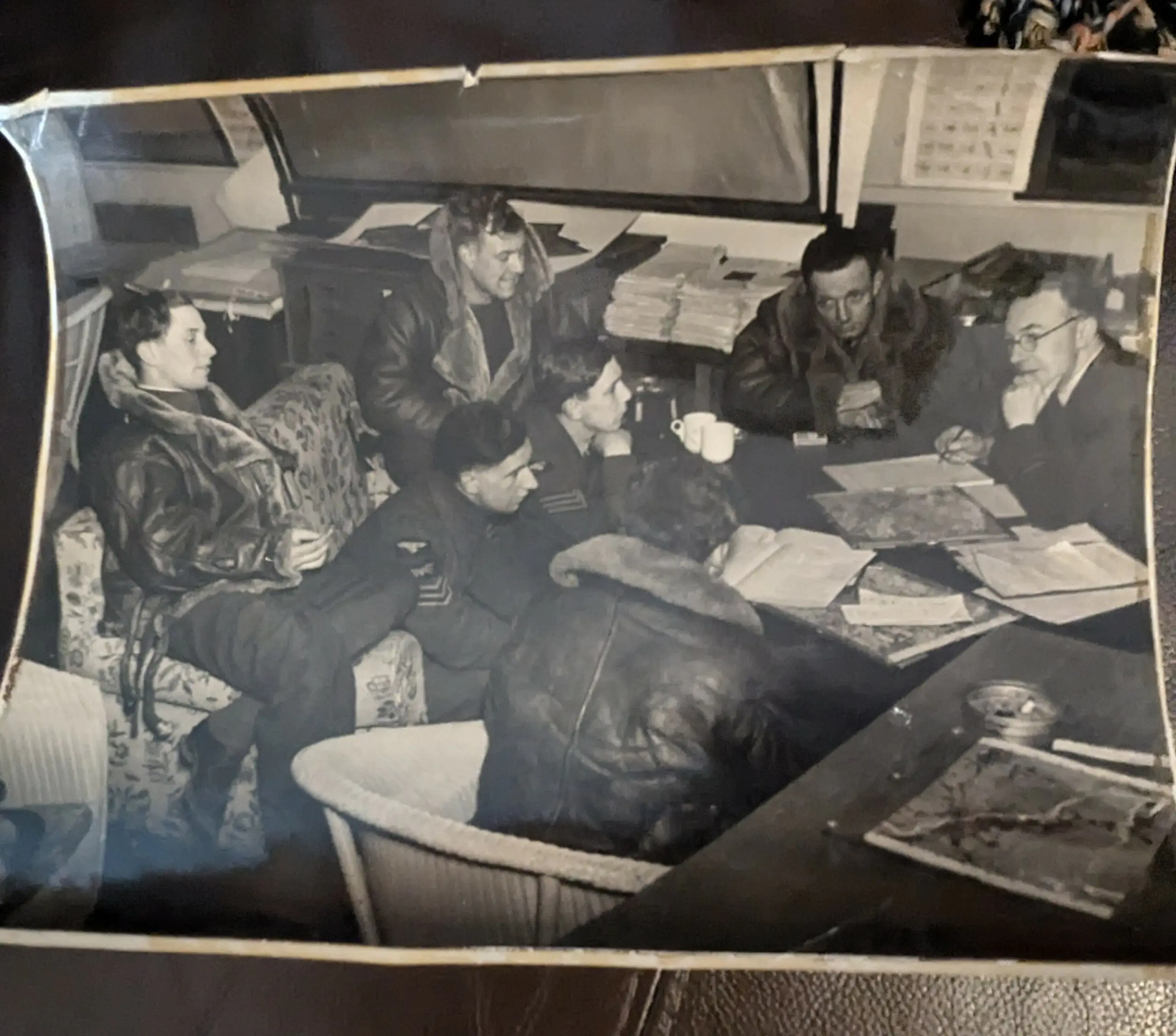

Transcript of Robert Jefcoate’s diary of time in Burma, originally sent to Charles Savage and recorded by Amelia Jefcoate.

We left England on 2nd January 1942 and on 23rd reached our destination at a drome in South Sumatra. This trip out was all sand and sea, sand-sea until we hit Burma and then it was sea and jungle. Maps and wireless were almost entirely useless from then on luck and good guesswork taking us on.

We hung on in the jungle there until the first week of February. When all our remaining crews went to Palembang as a labour squad.

Here we unloaded ships, just south of the line, the coolies having packed up when the bombing started.

By then Malay was in Jap hands and they were pounding us. On Friday 13th we had a severe raid. The next morning was free for me and I went to buy a watch. The sirens went before I reached the shop. I returned to the billets and there we got the order “Paratroops grab guns and get up the road”. I swiped a 303 rifle and jumped a truck. We unloaded and formed a road block hiding in the ditches and swampy jungle . Jap aircraft were everywhere with a few of our fighters unable to land on the occupied drome wandering aimlessly around.

A Dutch armoured car passed by with cries of good luck. Two minutes later a white flare . The Japs had thrown a bomb into the car killing the Dutch crew. Later, we were withdrawn and later still, about 11pm, I was detailed with 6 men to hold the far side of the ferry. (Everything had to cross the river that way). The order was “General Evacuation” For five hours I hung on there watching the stream of men going south. Firing was still going on over the ???. The AA fellows held out, using shrapnel at close range and by the late afternoon the drome was cleared by some of our people and the Dutch. At about 5 o’clock I was told to return to the billet, pack my kit and hang on till next morning. We “found” food and did what we could for the wounded. The civilians carried on wonderfully. By now, most of our people had gone.

Late that night the remaining guns and stores were blown up and during the night the oil wells were fired.

We slept but little. By dawn next day the oil wells and stores were belching black smoke and the sky was obscured by it. Orders were “every man for himself” . I packed a bag of clothes, a small satchel of books letter and my log book and with a cape, water bottle, rifle and ammo I set out. Across the road a soldier was smashing a spirit stove up. He was rolling drunk and was holding each bottle up and hitting it with a hammer. The Dutch stood and watched us go, I never felt so small in all my life. By the time I reached the ferry the bombers were circling in the smoke while fighters kept breaking out to machine guns. The river was full of equipment.

At the far side we set out to walk 3 miles to the railhead, a single line of troops on each side of the road, every few minutes we dived into the ditches to escape a low flying Zero then out again and on. At the railway they said it might be hours before a train left . Later we got a lorry and went south. We saw many lorries off the road n the flooded fields and one hurricane crash landed when the field was occupied. Eventually we reached our original base , the aircraft had run out of bombs attacking the incoming invasion fleet and were tying USA type bombs onto their racks and using the guns. Our officers – we had got together by then – left us and n the twilight I got into an Australian Squadrons petrol bower, with my kit all in a bus, I did not see that again.

South again, through the dark with the clouds lit by great fires. After midnight I was dumped out at rail siding and stowed away among crates in a steel wagon. I went to sleep and later found that we were moving.

We reached a small port around 10am. Dozens of new American civil cars were standing about in various stages of wreckage. The Dutch families drove there and then wrecked their lovely cars and pushed them into the water. Cigarettes were available in thousands for all who cared to carry them. I finally passed through dock sheds piled with every sort of goods including the civilians heavy stuff and into a tiny coasting vessel. Below deck was crowded with civilians, white and brown, we were on deck the whole time. At night I used my ammo pouch and cap for a pillow and wedged myself as best as possible , the tiny boat made very rough going of it. By next day we were very hungry but only a little rice and tinned herring were available eaten out of dirty fish tins. Why no one was poisoned I know not, water was almost unobtainable. A baby was born between the decks. We washed in a little sea water, our beards were pretty good. Three of us, an Aussie, a Canadian and I talked of our own countries and they laughed about our fireplaces in bedrooms. On the third day we anchored off harbour . A cruiser of the Dutch navy came in she was to be sunk next week, later we crept up the channel and docked.

Here the Dutch efficiency was at its best , a special train was waiting and away we went. I slept on the floor under the seat. Sometime during the night we stopped at a station and our Dutch friends had trucks waiting to take us to a school. Here we found heaven – cocoa sandwiches and clean straw to sleep on. Next morning we managed a wash and shave , the first for a week, still the same clothes however., then down town to eat a square meal, the receipt went home some time ago. Poerwockerts – I think that’s right.

I met a Dutch soldier who spoke good English in a room at the station with views of Lincoln on the walls. His family lived in Palembang. What happened to them? What hope could I give him? Late at night we got news of our moving next morning. So to bed again, then off early the next day for a wonderful train journey. I sat on the observation platform most f the time. It was a wonderful journey through a wonderful land, but more of that some other time. Next evening we reached Bataria and I remember the boys (we were with an Australian squadron) all singing Waltzing Matilda outside in the dark. We went by truck to some army barracks and slept on concrete for a change. Next morning we did nothing, after giving details of ourselves and our units. Around 10 o’clock I said “that’s a lot of planes” Then realised it was too loud a noise for the few kites our folks had left. The sirens went soon after the raid began. I “borrowed” a steel helmet (still have it) and spent an hour down a hole watching an odd dog fight or so.

During the fun we were rounded up and as the all clear went we boarded trucks for the station again, this time by the super electric railway to the town where our unit was stationed. Next morning to the drome and a fleet of Jap bombers escorted by Zeros swooped over and we thought we were going to be left alone in peace until the fighters and spent 45 minutes blowing up our kites. Hoods open, hair streaming in the breeze they had wizard fun – no opposition. I too had great fun with a tree as protection. I had to see where the next one was coming and dodge round the tree to the other side – very exhausting. After that we hung around several days and then some of us were told we were gong. As our skipper was ll at the port of arrival our crew was on the list – only complete crews being left, that’s why Scarbrook stayed.

Once again to Bataria where we had to give up all our weapons and I lost the 303 rifle that I had carried so far. On again in the night remember I remember seeing the southern cross on one side of the train and the Pole Star on the other. Very late that night we reached the port and boarded the ship. It was already packed, our skipper, still ill was there. The boat was a 2500 ton tramp steamer with room for perhaps 6 passengers nearly 200 of us were crammed aboard. The deck and two upper holds were already full, so we had to go down to the third hold.

Everyone slept where they could always on iron, and being around crossing the line, it was pretty hot. I slept without any clothes and on 2 towels and always awoke quite exhausted. We sailed next evening: next day the Jap battle fleet were outside.

We had an uneventful run across the equator to Ceylon. Food was very low and we had to wait for upwards of 2 hours for every meal. At first we had 2 meals a day. Later we had a few biscuits at midday. Water was low. After a few days I used to scour the decks and gutterings for odd scraps of biscuits.

A great crowd waited patiently outside the crews cookhouse for anything left over. Meanwhile the officers had a deck, the top one, to themselves. Their food was poor but it was well cooked. We saw nothing of the four padres on board.

On the Sunday we were at Colombo, someone asked if a short thanksgiving service could be arranged. The padres had all gone ashore.

We took about 10 days to reach Ceylon. I lost count count but it was around 10. By then 4 had died and we were all very weak. We hung around in port for four days before being transferred to a regular troopship – paradise to us. That took us to Karachi as you know. There the station C.O addressed the officers and told them that he did not intend his men to be demoralised by “any run away rabble from the Far East”, such was our welcome back to India.

Robert Jefcoate joined the RAF in 1939 having earlier in the year tried to join the RAF Volunteer Reserve but they insisted he had a sinus operation first.

He was a wireless op and trained at Yatesbury, Wiltshire, passing this training in July 1940. He was then sent to Operational Training unit at Harwell, south of Oxford. Later, posted to squadron 37 at Feltwell. He, and his other crew members survived a right off crash here. He was involved in several bombing raids of Dusseldorf and Cologne amongst other cities. His log book also shows a lot of times that raids were called off due to bad weather or other operational difficulties. His diary also shows a few fun times, hitching to see his girfriend (later wife), going to the cinema, a concert etc.

May 1941 all bomber command were briefed to attack the Bismark at all costs using B bombs (a sort of mine). Later this changed to the Prinz. Awful weather apparantly so no bombing.

In May 1941 they crashed in St Eval harbour, Gibraltar earning Robert a membership of the Goldfish club.

1st August 1942. Robert had volunteered to serve overseas as they were asking for radio ops. He flew in a brand new Hudson bomber and was using a totally different radio (Bendix rather than Marconi). They arrived in Palembourg Sumatra on 23rd January 1942. On 1st August there was panic as a Jap naval group was heading to the Bay of Bengal. Every bomber was kitted up, the weather was extremely bad (cyclone) and the bomber in front of Robert’s burst into flames on take off as it hit a road roller because of the the wind. Luckily the crew bailed out. They later took off , did their search in high wind and heavy rain. After 7 hours, fuel was very low and there were no identifiable landmarks. Robert had tried to radio several times but no reply. He sent an SOS as fuel was now zero . They spotted a small island off the coast (Shortts Island), They took up crash positions but landed in the ocean. Luckily nobody was hurt and they were eventually picked up in a motor boat by local people. So he joined the Goldfish club twice over!

In January 1942 he was posted to what was then Burma. The journey was disjointed, guess because of refuelling and was as follows:

Gibraltar – Mata

Malta – Cairo

Habbanah (Iraq) – Smarjah (Kuwait)

Smarjah – Karachi (Pakistan)

Karachi – Allahabad

Allahabad – Calcutta

Calcutta – Toungod

Toungod – Rangoon (Burma)

Rangoon – Sabang (indonesia)

Sabang – Packembaroe

Packembaroe – Palembang (Indonesia)