1924-1944

By Elinor Florence

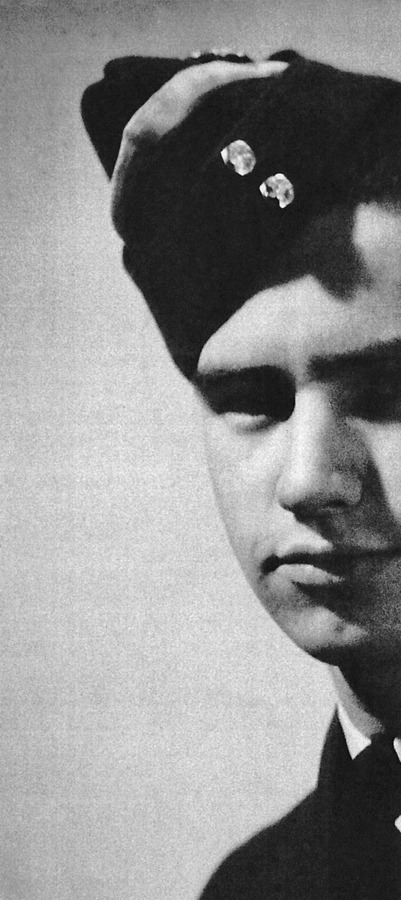

Jack Dye, a brave young bomb-aimer from Regina, Saskatchewan, saved everyone on board his Halifax bomber in this terrifying incident that took place on June 3, 1944.

Jack Dye was born in Regina on July 16, 1924. His parents were Clarence and Gladys Dye, and his sister, Betty was four years younger.

Jack joined the Royal Canadian Air Force on his 18th birthday in 1942, received his commission in July 1943 and went overseas. He flew with RAF 77 Squadron in Elvington, Yorkshire.

On June 3, 1944 (just three days before D-Day) 105 Halifaxes were sent to attack the marshalling yards at Trappes, southwest of Paris, and another sixty-three aircraft to raid coastal gun batteries in the Pas de Calais.

The attack was part of the D-Day deception plan. The raid on Trappes was carried out in clear moonlit conditions, and was to prove costly.

The German night fighters were able to take full advantage of the clear conditions and they ravaged the Halifaxes. Fifteen were shot down. No. 158 Squadron lost five crews, 76 and 640 lost three each.

Flying Officer Doug Morrison from Calgary, Alberta, was pilot of a Halifax Mk111 from 77 Squadron. Doug Morrison had reasons to recall the events of that night.

“Quite suddenly, as we approached the target area, but while still some distance ahead and below, it became increasingly bright as flares and marker flares exploded into action.”

“As we closed in on the target and began our bombing run, we could see aircraft above and below and on both sides of us. The cloud, smoke, flares and markers below us, and the aircraft all around us, presented a most impressive sight.”

“A few verbal course commands over the intercom from our bomb-aimer, Flying Officer Jack Dye, and we heard the familiar: ‘Bombs Away!’ We cleared the target and then made a turn to starboard to head for home.”

“Suddenly the urgent voice of the rear-gunner, Scotty MacRitchie, shattered the steady drone of the engines: ‘Corkscrew port!’ I responded immediately as tracer laced overhead. We continued evasive action until Scotty gave instructions to level out.”

“About two minutes later, there was a blinding flash and an explosion. Smoke, dust and pieces of aircraft flew in all directions. We began to corkscrew to port, but soon realized it was too late for this fighter pass.”

“A quick check revealed the port inner engine to be on fire, and a large, gaping hole in the side of the fuselage above the navigator’s table. Our flight engineer, Sandy Moodie, announced that he was shutting down the port inner and activating the fire extinguisher button. The fire was soon out.”

“I then initiated a crew check and all replied “okay” except bomb-aimer Jack Dye, who had been hit. Jack was still lying in the bomb-aiming position, so navigator Tommy Melvin assisted him to the rest position aft of the wireless operator’s table.”

“A short examination of Jack’s injuries disclosed multiple shrapnel wounds to his legs and back from the cannon shell that had exploded over the top of him. Tommy stopped the bleeding and made Jack as comfortable as he could before returning to his navigator’s position.”

“In the meantime, I had adjusted course according to the magnetic compass since the gyro-compass was acting up. A further check of the aircraft revealed that all the flight instruments had been knocked out, and all our charts as well as the navigator’s bag had been sucked out of the hole in the fuselage.”

“By this time we had left the brightly-lit target area behind us, and were feeling more comfortable with the darkness all around us as we continued on our northerly heading.”

“After a period of time, perhaps thirty or forty minutes, the wounded bomb-aimer asked if we would move him up to the second pilot’s station, which he normally occupied during takeoffs and landings.”

“He was moved into the seat beside me just as we emerged from under cloud cover. Above us we could see the stars shining clearly overhead. Jack asked what course we were on, and I replied that we were flying due north by the magnetic compass.”

“His quick reply was: ‘We are not flying north, we are going due east! Look, the North Star is directly off our port wing!’ Sure enough, we were heading straight for the heavily-defended Ruhr Valley!”

“Eventually, after what seemed like an eternity, we crossed the coastline and before long we saw the welcome shores of England. We knew we would need identification to enter England but our list of ‘colours of the day’ had been lost with the navigator’s bag.”

“We fired off several white signal flares as we crossed the coast, hoping our fighters would identify our Halifax as friendly. We broke radio silence to request an emergency landing, and received landing clearance. At least one fighter could be seen following us. The lights came on below us and we began a descent without any flight instruments to guide us.”

“As we circled around trying to judge our height, the runway lights came on. This helped, and we lined up for a landing, not knowing our airspeed or height, and flying on only three engines. Our first approach failed, as we came in a bit too high and fast.”

“The next approach we got down okay, just stopping as we reached the end of the runway. We later learned that we had landed at West Malling aerodrome, a fighter field with short runways.”

“An ambulance rushed up to where we stopped to assist the injured. Jack Dye insisted on walking unaided to the ambulance.”

“He turned, saluted, and was then whisked away. We never saw him again.”

“He died two hours later – a gallant man who had saved our lives.”

See Jack’s entry in our Losses Database here

For more Veterans’ Stories see our Blog Space here