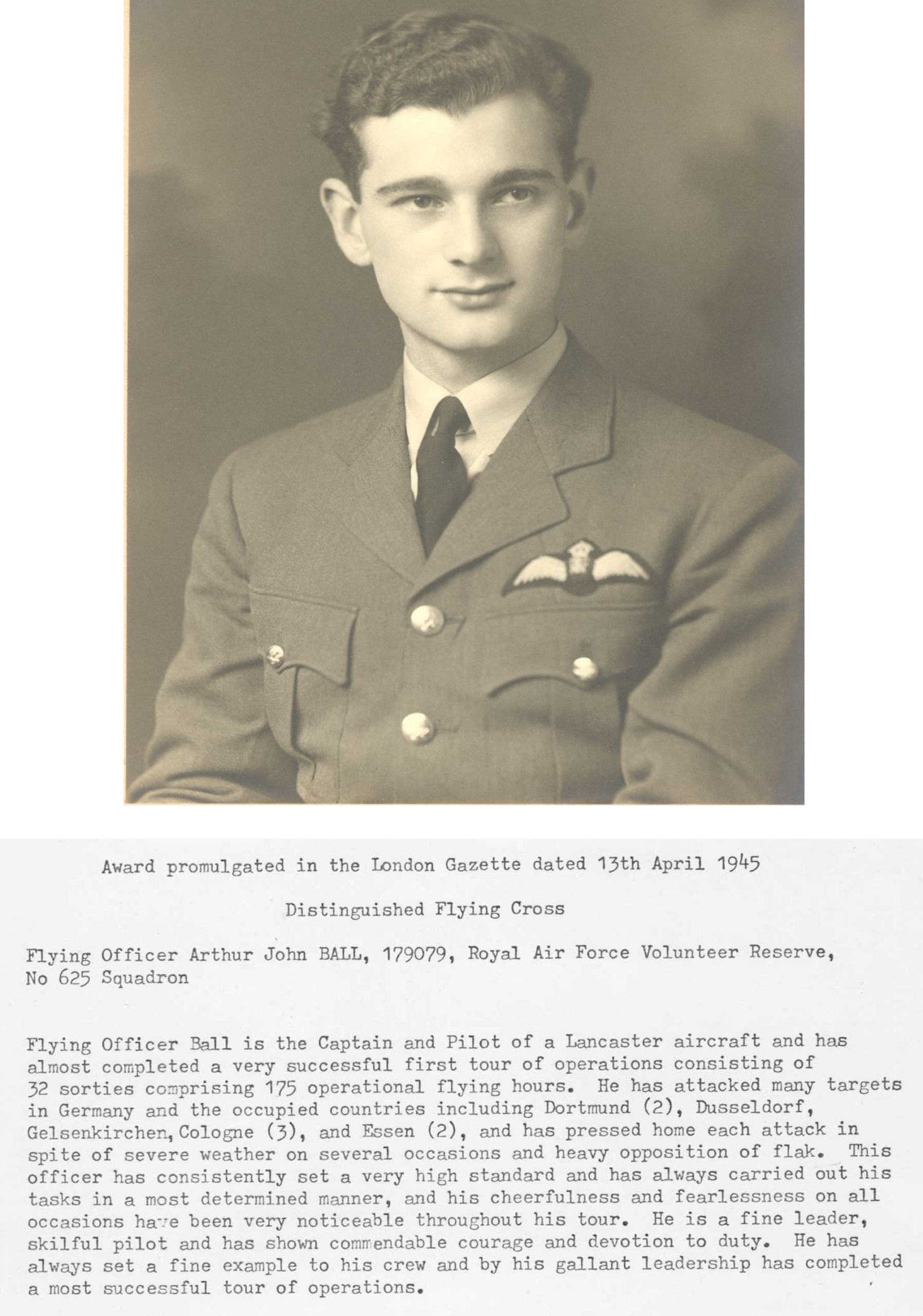

by Arthur John ‘Jack’ Ball, DFC

I’ve wanted to fly since I was a boy. Living under the circuits of two famous aerodromes presumably had an influence on me and I went through all the usual stages, reading magazines, building models and visiting air shows, finally joining the Royal Air Force. Many good books have been written about the period covered and many survivors’ tales have been told, so I will try to limit myself to the facts as seen through one pair of eyes and to convey the flavour and attitudes of the times. These are so important, yet difficult for succeeding generations to appreciate. I’ve regretted not discovering more about the lives of those who went before me, so I’ve included a sketchy piece of family history – if only I’d asked more questions or paid better attention. It is with this in mind that I hope that what follows will be of interest to some.

I was born in 1922 at 9 Goldsmith Lane, Roe Green Garden Village, Kingsbury, Middlesex. My brothers, Henry and Richard, were then ten and nine years old, my sister, Joan, was seven. A famous architect had designed the village in 1917 to house workers at Airco, who had been building aircraft for the Western Front, and it earns a mention in the RAF Museum at Hendon. The wing of a surplus airplane formed the roof of our chicken house, until it burned one Bonfire Night.

It was a delightful place to be raised. In those days, no neighbours owned a car, the front gardens, grassed and unfenced, were a communal play area and we were surrounded by safe, open country. Our roads were travelled by the horse-drawn carts of the baker, milkman and fishmonger, with occasional street singers, muffin- or onion-sellers crying their wares. Towards dusk the lamplighter would appear with his ladder, which he placed against the crossbar of the lamppost and went up to light the gas-lamp. Modernisation later gave him a long pole instead of the ladder to deal with the evening ignition and the dawn dousing. Mr Roberts was our lodger, a white bearded man who had been a colleague of my father at Airco. He was well-educated and used to chat to me: he told me that the snow came when the man in the sky was shaking his mattress.

In 1925 my parents bought a larger house, No.16. Solidly built, concrete floors throughout and a terrifying thermostatic gas boiler that I remember only my mother dared to light. Owing to the wartime timber shortage, the doors and windows were of poor quality. The combination of the construction and a roaring coal fire in the living room resulted in a freezing draught sweeping through the rest of the house in winter, when the water system frequently froze and the pipes burst. A few years later Mr Roberts died in his sleep. His will was on a postcard: ‘No flowers and no one to follow’.

In the summer holidays, I was packed off to my father’s home village of Eathorpe, on the ancient Fosse Way in Warwickshire. My grandmother’s thatched cottage dated from the 1700s, but an added, brick-built, adjacent washhouse and a combined privy and pigsty at the end of the garden, had brought it more up-to-date. Rainwater was used for ablutions, although there was a communal water-pump nearby. I had a plentiful supply of cousins in the area, whilst my father’s twin brother ran the village watermill on the River Leam.

My paternal grandfather had been a farm labourer, dying in 1911. Before that, my father had left the village to enter domestic service, travelling Europe and America before marrying a ladies’ maid, my mother, and setting up a shop in Battersea. It didn’t suit him and he re-entered service with Washington Singer at Norman Court in Wiltshire, before moving to Roe Green in the First World War.

My times at Eathorpe were idyllic: a summer’s round of village fetes and country carnivals, roaming the fields and riverbank. My grandmother was a tiny figure, always dressed in black, whilst my aunt cycled to Leamington Spa weekly to pick up a bunch of part-finished gloves. She spent the rest of the week sewing the seams. Money was in short supply and milk from the local farm was watered to last out.

Home was near two famous aerodromes, Hendon and Stag Lane. The latter was De Havilland’s base and most of the record-breaking flights of the time started from there. Hendon was the home of the annual RAF Pageant, a national event that drew huge crowds, packing any open spaces for a view, whilst traffic jams blocked the road for hours afterwards. The show was spectacular: it included the apparent shooting down of a WW1 observation balloon with the attendant observer descending by parachute, and the destruction of a fort, inhabited, it seemed, by blacked-up airmen dressed in bed-sheets. Rehearsals for the great show went on for weeks above our house to my delight and my intentions for a career crystallized.

My mother’s father, in his eighties, would come by pirate bus (independently operated, they would scoop up all the passengers just ahead of the regular bus) to sit in our garden with his binoculars and enjoy the mock combats. A dapper man, immaculate in a dark suit, white Panama hat, diamond tiepin and silver-topped walking stick. He was a man of property; my mother had been privately educated for a while when things were good.

In 1938 the Munich crisis occurred when Neville Chamberlain sold Czechoslovakia down the river to preserve peace and, incidentally, buy time to put our defences into a better state. There was a big flypast that year of eight hundred aircraft, mostly obsolete: Heyfords, Harts and Blenheims, to bolster morale. I remember seeing a large number of Avro Ansons included, a civilian passenger airplane, pressed into service with Coastal Command.

I had to finish at Kingsbury County School in 1938, as I was needed to contribute to the family finances (my siblings had been at work since they were fourteen and had continued their education at evening classes) and my father’s health was bad. I had been planning to apply for a short-service commission – four years and £400 gratuity – as a pilot when I was eighteen, so in the meantime I replied to an advert in The Daily Telegraph and was interviewed at the Mayfair branch of the Motor Union Insurance Co. They needed a good halfback for their football team and I was engaged as a junior at a salary of five guineas per month.

In those days there were 12d (denarii=pence) to the shilling, 20 shillings to the pound sterling and my guinea was worth 21 shillings. My ‘workman’s’ return on the tube was 9d, whilst pie and beans in a Savile Row café was the same. I ate a lot of pie and beans.

There were four office boys; I was the low man on the totem pole. The men ranged from twenty-one years up to grizzled veterans of the trenches in their forties or fifties. The office opened at 0930 but my ‘workman’s’ ticket required me to be at Green Park by 0800, so there was plenty of time to explore the West End on fine mornings and I was surprised to see so many people sleeping in Green Park. Bad weather meant coffee and a 1d newspaper. There were eight girls in the office, out of sight in the typists’ room.

When the war came the twenty year-olds were called up and the boys volunteered for their choice as they became eighteen: one to the Navy, a couple to the army. After Dunkirk and the surrender of France in 1940, I joined the Local Defence Volunteers (later the Home Guard). On fine evenings we would crawl around wasteland learning how to raid enemy trenches as it was done in 1918. We were issued with armbands to denote our combatant status and once we had a grand mustering of all local units. A fellow member was Charles Lofthouse who had been a year above me at school. He was soon able to join the RAF, and after a short and distinguished career, became a prisoner of war.

By summer 1940, there were daylight raids on London as the Germans switched from attacking the airfields. Transport became unreliable so I cycled to work and checked out the damage. I remember standing in Piccadilly watching our fighters attacking some Heinkels and realising that I was next to Billy Bishop, the Canadian fighter ace from the previous war. He was muttering to himself, but whether imprecations or instructions, I know not. Then an Air Vice-Marshal, he looked too big around to get into a cockpit.

At night, when the sirens sounded, our orders were to report across the fields to HQ at the British Legion Club, but when the Blitz started in September 1940, the futility of this became apparent. The gunfire and thump of bombs happened every night. The drinkers in the Club did not appreciate our presence and we could not sleep through their noise and smoke. A few bombs fell on our village with casualties.

Equipment started to trickle down, gaiters and bayonets, then US 1917 pattern rifles and denim uniforms. The high point of my Home Guard career was a dusk patrol around the village with an elderly veteran who must have been in a Bantam Battalion. We both survived.

The RAF

On my eighteenth birthday I went to the Drill Hall in Edgware for an aircrew selection board. Waiting with me was a pleasant public schoolboy who rejoiced in the name of Gerald Francis Barnett Newport–Teignley, if I remember correctly. He told me that he’d been recommended for a commission. I was pleased just to have been accepted. We both opted for immediate entry on ground-defence duties; the alternative was to wait at home for a training vacancy. I was called to RAF Uxbridge for a few days, where I passed the medical examination and returned home to await instructions.

On 25th November 1940 we arrived with other recruits at Blackpool for six weeks of training. I was billeted in a small, comfortable hotel in South Shore with a couple of older fellows, one smooth, one off the farm, and a number of Polish officers who had escaped through Roumania and France. Later, prosperous families fleeing the Liverpool bombing joined us.

Food was meagre and it was clear our RAF rations were being diverted. Of the fourteen shillings due to me each week, I had allotted seven to my mother and the rest went on food. I fondly remember the different varieties of tripe available at the United Cattle Products restaurants.

Blackpool was a windy town and there was plenty to do if one had money. We drilled, marched hither and thither, learned to use a rifle. Twice a week we marched along the promenade to the Derby Baths for a shower and swim. I couldn’t swim. It wasn’t much of a Christmas either.

In January 1941, a hard winter with snow, fifty of us arrived at Kenley, a fighter airfield south of London, as the Main Gate guard. The airfield had taken damage and casualties in the Battle of Britain the previous summer and was very heavily defended by units of the Irish Guards and Essex Regiment among others. They were out on the perimeter; we just had responsibility for the gate and some 20mm Hispano-Suiza AA gun-pits close by. Known as Kilby’s Killers after our CO, we were clearly more of a danger to each other than the enemy. Getting out of bed one morning, I watched the sentry coming off guard fail to clear his rifle properly. The resulting bullet went through the just-vacated next bed, split on the frame and ricocheted via the wall into the ear lobe of the early riser. Watching the blood pour through his fingers was a salutary lesson.

A minor irritation was the total absence of light bulbs, bath plugs and toilet paper from the washrooms, which made evening toilet an adventure on those winter nights. Such items had to be commandeered from wherever.

There was a Bristol Beaufighter in one of the hangars. Still on the secret list, it became one of the great weapons against enemy shipping. I enjoyed climbing over it. The days were spent at ground classes on related military subjects.

After a month, about ten of us were detached to Redhill, a satellite airfield used by the Hurricanes to re-arm and re-fuel. It had been a flying club and facilities were limited. We seemed to be the only defence, having two sets of stripped twin Lewis guns, 1917 pattern on AA mountings, gratefully sold by the USA. Patrolling at night was nerve- racking: the hangars were full of interesting old aircraft but were unlit, whilst out on the airfield there were desultory shots from airmen potting rabbits for the local butcher. We did have an Armadillo for tackling enemy paratroops. This consisted of a flatbed lorry with a loop-holed, single brick enclosure on the back.

I opted for duty on the crash tender which, because of limited aircraft visits, gave me a chance to acquire some valuable time on the Link Trainer, where the instructor was grateful to have some interest shown. This was the counterpart of a modern simulator. Its purpose was to brush up your instrument flying and to teach associated procedures such as radio range and blind landings. You sat in the cockpit with a hood over, whilst the instructor introduced rough air, cross-winds and other difficulties. Your course was reproduced on a glass-topped table by a crab-like copier. I found it fascinating and always got as much time on the Link as possible.

Most of the men there were ‘old sweats’, who had been in France with the British Expeditionary Force and had escaped one jump ahead of invading Germans, minus most of their equipment.

Training Command

Time passed slowly, we wondered if we would ever get to fly, and then the magic posting came through. In April 1941 we went to Stratford-on-Avon as aircrew cadets with a white flash in our caps and a spring in our step. Quite a number of squads there were ex-army who’d got tired of inaction and had been encouraged to transfer. They could easily be distinguished by their superior turnout and the crash of their steel-shod boots when marching. The only things I remember are the cross-country runs and the church parades. On the latter, the Sergeant ordered Roman Catholics and Jews to fall out, and then divided the squad into ‘C of E’ and ‘Other Denominations’ (‘ODs’). By the second week I decided that my sermons were too long and opted for the ‘ODs’ thereafter.

This was a pleasant fortnight, but just a sorting out before we went on to an Initial Training Wing at Aberystwyth. Here we were living in a sea-front hotel and the training was getting interesting. I was picked for the Arnold draft, which sounded like a plum posting. General Arnold of the US Army had arranged for RAF aircrew to be trained in Florida and Arizona etc, where the weather was kinder to intensive flying. As the USA was still officially neutral, we were to travel in civilian clothes and were duly measured for grey chalk-stripe suits and black berets.

At the last moment the numbers were cut and I was taken off the draft. My disappointment turned out to be misplaced, when over the years we got stories back of the draftees’ mixed experiences. Here I teamed up with Stanley Stilwell, another who had been a year above me at school. Tall and handsome, he was a good athlete.

By the middle of June 1941 twelve of us arrived at Burnaston, No.16 Elementary Flying School, between Derby and Burton-on-Trent. It was a grass airfield where now stands a Toyota factory. Instead of the usual biplane trainers – Tiger Moths etc – there were low wing monoplanes, Miles Magisters. We were a mixed bunch, some from ground defence, some re-mustered regulars, one from the army – Richard Board.

The next six weeks were as good as it gets. My instructor was Warrant Officer C.G. Unwin DFM, who had gained fame in the previous summer’s air battles. He was a gritty, quiet Yorkshireman who missed the front-line life. He had a habit of taking over the controls and diving in pursuit of any passing aircraft. I was surprised and pleased when he sent me solo after seven hours of training – a tribute to his teaching.

The weeks went too quickly, as the rudiments of aerobatics, forced landings, map- reading and instrument-flying were drilled into us. I managed to sneak off on crosscountries sometimes, in order to do a steep turn around my grandmother’s cottage at Eathorpe.

Stan and I hitched a lift one Friday on a weekend pass but the driver had started from Glasgow and we all fell asleep. An irate householder at Stony Stratford woke us at 6am Saturday, complaining that the engine had been running all night just outside his bedroom window. We decided it was safer to take the train back to Burnaston on Sunday.

Come August we were at Wilmslow in Cheshire, a transit camp, where the bedding seemed never to have been changed. We were being sorted out for overseas and it was there I first realized how complex was the Empire Air Training Scheme. There seemed to be hundreds of aircrew cadets milling around waiting to be posted to exotic places.

After a week we were in Greenock on a steamer, which many opined was too small to brave the Atlantic. Fortunately it took us only to SS. Leopoldville, a Belgian liner, dirty, allegedly from carrying Italian prisoners, where we had to sling our hammocks in close ranks. There were other decks below us stuffed with troops and, at the bottom of the pile, were the Jersey Coastal Artillery, exiled since the loss of their island. They had been selected to defend Iceland, which we had invaded the previous year.

It was an unpleasant journey, made at top speed in foul weather with our three escorting destroyers (four-funnelled surplus American, swapped for British bases) rolling wildly. After the first night swinging uncomfortably with my nose between two pairs of feet, I found a comfortable carpet under the officers’ saloon table. We were able to buy huge chocolate bars on board, but after three nights of bouncing around, I soon became sick of it and it was two years before I could face chocolate again.

There is a memorial plaque on Weymouth promenade to the liner Leopoldville and the eight hundred men, mainly American troops, who died in her when she was sunk in the Channel at Christmas 1944. At Reykyavik, we transferred to a hillside at Helgafell, bare except for two empty Nissen huts.

We slept in full flying kit on the floor. It never got dark and the days brought jolly route marches over treeless hills, with sometimes a glimpse of an unfriendly blonde holding back an unfriendly hound.

Food was bully beef and hard tack and we went to the stream at the bottom of the valley for our ablutions. A real treat was to go in the evening to the hot springs where the mixed toilets had no doors, but were comfortable, and you could wade in the pond to shave.

After five days we embarked on HMS Ausonia, an old Cunarder out of Liverpool. She had a Scouse crew from the Merchant Navy on T124X Articles, a few DEMS (defensively-equipped merchant ship) gunners for the two 1897 pattern 6” guns and a smattering of anti-aircraft guns that we were deputed to man. When we took station in the centre of the leading rank of a convoy of some fifty ships, Ausonia proved to be the flagship.

Around the convoy could be glimpsed the escorting destroyers, whilst on either flank in our row, there was a CAM (catapult aircraft merchantman) ship with a Hurricane perched on the catapult. If hostile aircraft appeared, it would be launched on a one-way trip to end in the sea. Sunday church parade saw our elderly Commodore in full uniform, sword dragging at his side, reviewing the complement. The civilian crew were naturally nervous that in the event of a German battleship appearing over the horizon, our Commodore would sail out to meet it as HMS Jervis Bay had done. It didn’t strike me at the time that in such an event we would have to go along. There was no alternative. The crossing was a boring eleven days, which put me off ocean cruising for life. It was enlivened by a concert and a boxing tournament to which the RAF contributed a professional clarinet player, two fencers, a stand-up comedian and a flyweight.

Our voyage coincided with Churchill’s meeting with Roosevelt on HMS Warspite, when they declared the Four Freedoms of the Atlantic Charter for which we were alleged to be fighting. The battleship was moored next to us when we berthed at Halifax, Nova Scotia, but the Prime Minister was not in sight.

The Canadian Pacific train we boarded was familiar from Hollywood films. Two-tier bunks at night on either side, shielded by heavy curtains. The train trundled slowly westward for four days, the food was excellent and at rare stops the locals provided apples etc. The scenery was not exciting, but going through Quebec Province it seemed that every tiny settlement had a gilded, domed church.

Empire Air Training Scheme

Eventually we arrived at Carberry, Manitoba, a small town set in a rolling prairie. The RAF had settled No.33 Service Flying Training School a few miles away where the Canadians had constructed three runways, huge timber hangars and a hutted camp. We were No.28 War Course but, unfortunately, I failed the ensuing medical due to eyesight and my career prospects hung in the balance. I went for re-examination the next day, pleaded a bad cold, and they relented. The thought of shipping me back to England may have been the deciding factor.

For better or worse, I then decided, somewhat selfishly, to commit to memory all four standard eyesight test cards then in use on RAF stations.

For the next three months we learned to fly and navigate Avro Ansons. Originally conceived as a six passenger aircraft, the RAF had bought a large number in the desperate expansion days of the late thirties. Fitted out with a turret, guns and bombs they were used for convoy duty around the coasts. Unmodified they were ideal training aircraft.

They were a delight to fly, safe and stable, but on these early models the flaps and undercarriage needed a lot of effort on the hand-pump, whilst the brakes relied on a single air bottle, which quickly emptied. My worst moment came when the maintenance Flight-sergeant asked me to taxi an aircraft to a new position, without warning me that the air bottle was empty. I found myself heading for a line of aircraft with the ground crew desperately hanging on or trying to throw chocks under the wheels. I cut the switches, they succeeded and I was saved.

In daylight the flying went well, but at night I realised that I could not see the glide path indicators, red or green, to which the instructor, Flying Officer Clough, was directing me. It was difficult enough to pick out the airfield in the profusion of Canadian lights, but I never actually tried to line up on the main road. I soon learned to judge the glide path angle from the perspective of the runway lights. Later on 625 Squadron, Clough was reduced to the rank of Sergeant for repeated low flying.

On the first free weekend, five of us hired a taxi for the two hundred and forty mile round trip to Winnipeg to stay in the YMCA. I knew I had relatives in the area and wrote for their address.

Local families, especially those with spare daughters, were free with their invitations and the La Pierre family treated me as one of their own. One weekend, for a change, three of us went to Riding Mountain National Park. In searching for lodgings, each cabin door was answered by a large, black-bearded man in black trousers and white shirt. Apparently they belonged to a German religious sect, the Hutterites, doing forestry as their war effort. We eventually found accommodation and enjoyed the park facilities.

We had all been asked if we were keen on a commission, but my circle of pals, many of them regulars, decided to opt for NCO in the hope of staying together. Suffice to say I was young and foolish with little thought for the morrow. Came the great day, 5th December 1941, when the pilot’s brevet was pinned on my chest and I graduated as a Sergeant.

Pearl Harbour was attacked two days later, bringing the United States into the war and a rash of rumours about submarines off the west coast. By this time I had contacted my Uncle Frank who picked me up at the YMCA. He still had his Warwickshire accent and was superintendent of the city’s parks. I recalled the newspaper cuttings in my grandmother’s cottage regarding the annual chrysanthemum displays. Now I met my Aunt Ruth and four cousins, Bella, Arthur, Edna and Frank.

Of the new pilots, six of us were posted to 33 Air Navigation School at Mount Hope, Ontario. Many others went to similar postings around Canada: Bert Hauthausen and his clarinet went to Prince Edward Island, Stan Stillwell went to Patricia Bay on the west coast (to be killed within a couple of months) and another crashed the following year at a Gunnery School.

I got to Mount Hope a few days before Christmas 1941 in deep snow. Sergeants Baxter, Edinburgh, Gribble, Piper, Board and myself had first to be cleared for taking trainee navigators around the Ontario skies and bringing them back safely, despite where they wanted to lead us. I was assigned an Aircraftman wireless operator, Norman Lister, who was to fly with me for the next sixteen months, as we carted pupils on two threehour details per day or night, come snow or rain. He was the link to base by Morse code: we had no voice contact and got landing instructions by Aldis lamp. I also carried a small radio tuned to the Radio Range beams crossing the area.

Being the pilot in those days meant that you were captain of aircraft and full responsibility was yours, no matter what higher ranks were carried at any time. Mount Hope was a typical three-runway aerodrome of the sort built all over Canada, the UK and other places where the RAF was the main customer (later American military airfields were generally single runways built to the prevailing wind for tricycle undercarts). It lay on an escarpment a few miles from Hamilton, a steel-making city of about two hundred thousand people, nestled against the western corner of Lake Ontario. Our bombing range was on the Six Nations Reservation a few miles south. The aircraft were Ansons, some of which had been ‘winterised’ by lining them with hardboard, increasing the stalling speed.

On winter nights you either froze or sweated, depending on which aircraft you had been allocated. You sat there in full gear plus Thermogen in your boots, icicles forming on eyebrows or moustaches. Frequently, the pitot head heater failed, leaving you with no airspeed indicated. Nevertheless, I liked the night flights for the phenomena you sometimes saw: the moving ribbons of the Northern Lights, the ice crystals before the rising moon and the great ball of the red sun at dawn. Eye tests were given every six months, but an excellent memory got me through.

One night, snow and engine trouble forced me to land at what is now Toronto International airport. Because of the weather, we were ordered to return by train to Hamilton, glad to be wearing full flying kit despite the jeers of street urchins.

In summer, the problems were the cumulonimbus clouds building up as they traversed the Niagara Peninsula from Lake Michigan. By the time they got to us they were towering thunderheads. In flying, the weather was always the chief concern; although the forecasts were generally accurate, it was the unexpected for which you tried to prepare.

Many of the original staff had been co-opted bush pilots with great experience, but there was some concern amongst the navigation instructors that aircraft landed after exactly three hours, whatever the standard of navigation. The bush pilots tried to maintain that we were built on a magnetic mountain.

I was caught out one May night when we had been flying west along the centre of Lake Erie. The pupils were using astro navigation with the only lights below being the freighters ploughing west to Sault St. Marie or eastwards towards the St. Lawrence. We were battling a headwind clearly greater than forecast, as we had not reached the turning point and the trainees could not believe the fixes they had calculated. I had been keeping a weather eye on a big thunderhead to the northwest when we were recalled by radio. After crossing the coast I recognized Dunville aerodrome, but the weather ceiling was forcing us lower and near base we ran into solid rain and cloud down to the ground, so I turned back.

Unfortunately, in the meantime, Dunville had closed. No runway lights were showing, but in the lightning flashes I glimpsed the runways as I did a low circuit at a couple of hundred feet. I decided to aim at the central triangle, which I knew should be grass. With the pupils pumping the undercarriage down and full flap, I closed the throttles, held the stick back and prayed. Faithful Annie pancaked into waist-high grass. We sat in the blackness and pouring rain to get our breath back and waited for the transport. I had a lot of drinks bought for me that night.

The months rolled by, we were asked what our choice would be for an operational squadron and I put down ‘torpedo bombers’. A number of Polish officers came through as pupils, plus a few of my old school acquaintances.

We were on Canadian rates of pay that were advantageous and were working hard, especially at night flying. We had a Sinhalese Sergeant-pilot at the school, a delightful chap from a wealthy family. Unfortunately, he was refused entry to the dance hall in Hamilton resulting in our CO placing the premises ‘out of bounds’ to all ranks. The proprietors quickly apologised.

On free evenings we went to town, usually the cinema or ten-pin bowling. I had made some friends there through the Hamilton Players and they were generous with their hospitality. One of them, Arch Mullock, arranged a splendid trip for four to New York. We were busy the whole time meeting celebrities like Gracie Fields, who bought us drinks in the Astor hotel before she sang. Every evening we hurried from theatre to nightclub: my twentieth birthday party was in the Twenty-One Club as the guest of Frank Crowninshield, the editor of Vogue. I thought what a fine-looking bunch the attending naval officers were with their suntans and white uniforms. Later I realized they were the chorus line of the floorshow.

One afternoon I was leaving a bar when two elderly ladies waylaid me. Dr Pringle told me that she had been the first female medical practitioner in the USA; her companion, Maureen O’Flyn, had been a ladies’ maid in England before emigrating. They insisted that I accompany them to their suite in the Henry Hudson Hotel, which was piled high with boxes of pullovers. The only one that fitted me was in dark Australian blue, but it kept me warm for many years.

My closest friend then was Bernard Edinborough, the son of a policeman living near the Harrow Road in London. We sometimes used to spend weekends in Buffalo NY. Booking into the excellent Ford Hotel cost $4.50, which at that time was the equivalent of £1 sterling. Once we got to the bar, our uniforms excited enough interest to ensure a good evening.

On camp, home-grown talent provided light relief. We were lucky that the Edwards brothers put on hilarious acts for our concerts. Jimmy went on to fly Dakotas at Arnhem and star on radio and television.

There were mishaps: Jock Forsyth got lost and force-landed in Bad Axe, Michigan; Len Gribble became disorientated and put down in a moonlit field; a new pilot decided to go under the bridge at Detroit and hit the water; sadly, Richard Board (who had married a local girl) crashed with no survivors. Unusually, we were detailed to carry his coffin through the snow. He is buried with his companions in the churchyard at Mount Hope.

The year went quickly. Much was happening in the war which was passing us by. By April 1943 I was a Flight-sergeant with over eleven hundred hours of twin-engine flight time and was at last posted to Moncton, New Brunswick, the transit camp for overseas. There we went to the cinema, ate lots of steaks, walked the countryside and waited for a ship.

There was a scarlet fever epidemic and I was sent to hospital with a throat infection. It was so crowded that we less serious cases were packed end to end in the corridors. After three weeks the next fellow came out in chickenpox and in due course I followed. I was placed in a single room where I grew long hair and a beard, until the Matron looked in and kicked up a fuss. They found I was suffering from Bright’s disease, a kidney complaint and all changed. Thereafter the chef came each morning to find out what I wished for lunch and dinner. They put me through a battery of tests and several weeks of treatment. I recovered, went on leave, relapsed, met Des Dowding, a fellow patient, and finally boarded the mighty Queen Elizabeth on 12th September 1943 for a five day zigzag, unescorted voyage to Greenock. I was not alone. I shared a ‘hot bunk’ with a stranger: my turn was midnight to noon. We had two excellent meals per day, 5am and 5pm. There were some seventeen thousand American troops on board. We found that they were too good for us at poker, but they were sure the ship had been built in the USA. We arrived in Liverpool.

After two months in the Grand Hotel at Harrogate, where many of the RAF staff were famous sportsmen, I went to an advanced flying unit at Kidlington, near Oxford. These units were necessary because flying conditions were so different in the UK from Canada or South Africa. Weather, the blackout and the enemy each posed their own problems.

We flew Airspeed Oxfords, a lively twin-engined job, not quite as forgiving as the Anson. It was a hard winter again. The Australians and South Africans had not seen snow before, so sun-lamp sessions were arranged in the evenings. Each twin room in the wooden huts had a coke stove, but the fuel ration was minimal. The Aussies burned the steps to the huts and joined us nightly in raiding the coke enclosure. I was having problems with my throat and spent a lot of time grounded. Finally I was sent to the RAF hospital at Halton for a fortnight to have my tonsils out.

There was also a two-week detachment to Holme-on-Spalding Moor in Yorkshire for a Beam Approach course. Conditions were foggy which helped the reality of the situation and it was instructive and enjoyable. We shared the aerodrome with 78 Squadron flying Handley Page Halifax I with Merlin engines. These aircraft will be met later. According to an old friend from Mount Hope that I met, morale was low here as they were taking heavy losses. He was gloomy about the prospects. I saw from the official lists that Francis Newport-Teignley, with whom I’d joined up, was now a prisoner in Germany.

Bomber Command

In April 1944 I arrived at 30 Operational Training Unit at Hixon, near Stafford. By this time I was a Warrant Officer, the highest I could get unless I took a commission.

It was time to gather a crew from the other categories, which we now met for the first time. I approached a boyish navigator, Gordon Foot, who seemed happy to join me. I liked the look of a large, elderly Aussie, Mike O’Connor, standing nearby. He was a Bomb aimer but had also had navigation training. He volunteered to get a good Aussie wireless operator and I agreed. It turned out to be eighteen year-old Peter McGill from Woolamaloo. Out of the melee a pair of gunners approached me. They were short, stocky and elderly to my eyes. They had been pals through training in South Africa. Bob Job and Pat O’Malley admitted to their mid-thirties and came naturally as a job lot.

Mike O’Connor was a splendid man, thirty-six years old, calm, imperturbable and rather shy. He claimed to have been in a Western Australian rifle regiment that had been disbanded for insubordination, but I was never sure when he was joking. In civilian life he had been a gold mining engineer in Kalgoorlie and had prospected in the desert. Many years later I found that he had been raised in a foster family.

Gordon Foot was to fly with me for the next three years, eighteen years old, below average height, he looked so young that if he wore shorts when on leave, he passed for a schoolboy and travelled half fare. He was an excellent navigator, very precise and accurate, never betraying any anxiety.

We went to Stafford Baths for dinghy training, which meant stepping off the top board in flying gear. I had to be first. One of the crew was reluctant, but followed. Mike said to me later, “If push comes to shove I’ll hit him over the head and out he’ll go”.

We flew Vickers Wellingtons, designed by Barnes Wallis on the geodetic principle, capable of taking heavy damage, proven since the war began. Now classed as a twinengined medium bomber, they were easy to handle and roomy. The course was about eighty hours flying, with half at night, and consisted of long cross-countries identifying coloured TIs (target indicators) before turning for home, or fighter affiliation, where we tried to outmanoeuvre the fighters.

It all culminated in a trip to Holland dropping leaflets. We had an engine cut out over the North Sea, due to Pat, who was a passenger (no turret to man) kicking a fuel tap to ‘off’ in his sleep. On these flights, I landed using the Blind Approach system as often as possible. It was an early version of ILS (instrument landing system). With this, it was reckoned to be safe to let down through cloud to three hundred feet.

About this time the invasion of Europe took place and long columns of troops and tanks rolled south. I heard later that George Baxter, a friend from Mount Hope, had been lost with all his crew, mainly Canadians, in a disastrous raid against Wesseling oil refinery, when over a quarter of the Lancasters were shot down. Here I was commissioned to Pilot Officer.

Our next step in this long progression to operational flying was on 21st July to 1667 Heavy Conversion Unit at Sandtoft on Thorne Waste. Crews already there cheerfully told that it was known as ‘Prangtoft’ due to the crash rate of the Halifax I. Engines were cutting out because the fuel was fed from a large number of small tanks, the controls for which were hidden under a rest-bed back in the fuselage. It was too easy to select a wrong tank or cause a vapour lock.

Flight Engineer, ‘Jock’ Mackintosh, joined us here, pushing forty, a fine dancer: his tango was a delight to behold. His civilian experience was as a lorry driver, and he had something of a cavalier attitude to problems, but more importantly to me his eyesight was as keen as Bob Job’s, and it was reassuring to have a good lookout at both ends of the aircraft. His immediate job on the Halifax was to operate the fuel controls on my intercom instructions, thus solving the local problem (later Halifaxes were fitted with radial engines and more sensible fuel controls). Once engines were started, there was no chatter on the intercom and the crew reverted to addressing me as ‘Skipper’ and vice versa.

I was being instructed on ‘circuits and bumps’ by Ted Ellis, who had won the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal over Berlin with 625 Squadron. There was a crosswind and, on landing one fine day, I failed to cancel out all the drift, the result being that we left the runway at an alarming angle and sped across the grass, scattering football players on either side. Ted wanted to show me where I’d ‘boobed’ so we went round again. Unfortunately he got the same result. We laughed about it, but I don’t think the footballers or the crew were amused.

From Sandtoft we went to No.1 Lancaster Finishing School at Hemswell, near Gainsborough where, over three days, I put in eleven hours learning to handle the Avro Lancaster. This was an aircraft without vice. Easy to handle, sturdy, fuel cocks on a simple side panel and four throttle levers that fitted snugly to the hand. Sadly, to save weight, the ILS blind landing system had been removed and the armour behind the pilot’s head had been replaced with painted plywood. I belonged to No.1 Group which, I later learned, had a philosophy of carting maximum bomb load to the enemy. Anything else was secondary.

Ted Ellis CGM was the main reason that I and two other pilots applied to go to 625 Squadron. He described it as very friendly, a great CO and Station Commander. Unfortunately, the demand for this squadron was too great, and my pals with whom I’d spent many happy evenings, ‘Taff’ Edwards and ‘Jock’ McGonigle, were both posted to 101 Squadron down the road at Ludford Magna, to be killed, with all crew. They carried an eighth German-speaking crewman whose job was to give misinformation to the enemy night-fighters.

625 squadron was based at Kelstern, near Louth in Lincolnshire. The aerodrome, built in 1943, was high on the Wolds and could be cold and windy at any time of the year. The squadron had been formed there as soon as the accommodation was ready with “We Avenge” as the pointed motto. We arrived there in September 1944. The CO was a young and dashing Wing Commander, Douglas Haig, allegedly of that family; the station commander was Group Captain Donkin, a more venerable gentleman who could also stand on his head to drink a pint of beer if required.

We were sent off on a night cross-country trip for experience. After four hours we were diverted to Lindholme, Yorkshire, because of fog at base. Everything looked fine when we arrived, the runway lights being visible from above at a thousand feet, but as we made the landing approach all lights vanished when we entered the fog at three hundred feet and I had to abandon the landing. This was a very fraught situation: now I needed the missing ILS. The control tower had no reachable alternative airfield to offer.

I requested that the Duty Pilot, in a caravan at the threshold of the runway, fire Verey lights when he heard our engines approaching so that I could try to line up the giro compass on the runway heading whilst letting down on instruments.

I tried twice more, with Gordon getting me a radar fix to turn on to the runway heading, while Jock and Mike both strained their eyes for a glimpse of the threshold. Twice more we had to abandon. On a third attempt we saw the caravan as we passed over and I put the plane down. We finished up stuck in the mud off the far end of the runway, but safe and unbroken. It was a very lucky escape in which Gordon’s radar fixes and the Duty Pilot’s Verey lights were essential.

My first operational trip came the next night. It was as ‘second dickie’ to an experienced pilot, Flight Lieutenant Avery. I was a bit dismayed when he climbed in and put on a pair of spectacles. I sat in the Engineer’s seat during the flight and we attacked an airfield at Rheine-Salzebergen with twenty 500lb bombs in support of the Arnhem landings due on the morrow. We left it well cratered.

Our 12 Base Commander from Binbrook, Air-Commodore Wray DSO MC DFC AFC, came over to give a welcoming pep-talk. He had been shot down in the previous war and was known as ‘Pegleg’ as a result of his wounds. He was a doughty warrior who used to take inexperienced crews to Berlin and such places. The gist of his talk was, “don’t weave around trying to dodge the flak, just go straight through it”. I decided to adopt his credo.

I remember my fellow pilots fondly: Len Doward, Clem Koder, Sandy Lane, Geoff Perrott, Bert Hazell; Harvey Hewetson and Lloyd Hannah from Canada, Dave Mattingley and John Murray from Australia. The Brits among them had similar experience to my own: a couple of years spent training other aircrew.

The next day I was with my own crew on the Battle Order for a daylight attack on Eikenhorst, a V1 storage base in Holland, which we were to bomb from ten thousand feet. The V1 was the ‘doodlebug’ currently bombarding London. My gunners told me that when going for the ‘ops’ meal they were delighted to call out whose crew they belonged to.

No telephone calls in or out were then permitted. After the main briefing when the target, route and special hazards were pointed out, the other categories went to their own briefings. We picked up our first aid kits, emptied our pockets of personal items and finally were conveyed around the perimeter track to the dispersal points where the aircraft stood. The ground crew were there to discuss any recent faults that had been corrected. Lofty Parsonson, the rigger, and Jim ‘Sparks’ Docherty were great friends then and many years later.

Then we set about loading the mound of brown paper parcels of ‘Window’. These were the metallised strips cut to interfere with the enemy radar frequencies and the number of parcels varied with the length of the trip. On a long raid we hardly had room to move. The bomb-aimer was supposed to stuff handfuls out through a small opening, from approaching the enemy coast until we returned to the same point. This trip is retained in my memory because on my first sight of the strips, glinting as they flashed by, I thought they were tracer bullets. I was disabused of this idea when a large brown paper parcel came tumbling past.

We had two main aids for the navigator. Gordon was an absolute wizard with ‘Gee’ which was accurate over the UK, less so as you went away. The other was code-named H2S. This painted a picture of the ground below and could normally pick out towns, rivers and coastlines. Unfortunately, the night fighters could home on to its transmissions, so we normally only used it over the target. Clamped to it was a camera that recorded the screen when the bombs were dropped.

Similarly, Peter had a screen, code-named ‘Fishpond’, which was believed to show any night fighters attacking from underneath, but as the Germans could also home on that, we used it rarely. One of his jobs was to search the radio frequencies until he located the German Fighter Controller and then transmit on that frequency from a microphone in an engine nacelle.

I was in a Nissen hut with three other pilots. That winter was brutally cold on the Wolds and there was a temptation to keep your ‘long johns’ on whether flying or not. This had to be resisted.

My crew, who shared a Nissen hut, had melded well, although some confided that they found Pat O’Malley’s habit of oiling and exercising his suitcase hinges every night to be a trifle wearing. I paid them a visit to witness this but took no further action. Mike also told me that young Peter the wireless operator was very nervous, tended to sit on the main spar and recalculate the odds against us after each trip. I regret that I did not have the nous to discuss this with Pete and possibly avoid his later illness. He had a frightening task over the target, having to go off-intercom and back along the fuselage, carrying portable oxygen and a short length of broomstick, to ensure the six-inch diameter photoflash went automatically down its chute. This lit the target for the photographs that hopefully proved we’d been there.

Initially on trips I carried my revolver in a holster, but soon got tired of this and left it in the hut. Thereafter I just flew with a gas mask case on my chest like a horse’s nosebag, full of sultanas made freely available by a Dominion government. We were equipped with various escape items: a compass in the form of a trouser button, a knife in the top of a flying boot (to reduce them to a pair of shoes) and a map printed on a silk scarf.

We had passport photos taken dressed in a sports jacket and tie. The idea being that, having contacted the Resistance, new documents could be rapidly made. Naturally, only one jacket and tie seemed available to the photographer. The Germans revealed after the war that they could usually tell which squadron prisoners belonged to by the pattern of the tie.

Looking back through my logbook, it seems that we flew on most days. If there were no operations scheduled for us, we were away to the bombing range or on fighter affiliation.

On a trip to Calais to attack the heavy guns that were bombarding Kent, the targets could not be seen through cloud. We had a Master Bomber there who ordered us to take the bombs home. This was a new experience, rewarded by the sight of the first pilot home landing too fast with his wheels up and sliding through the far fence. This was a man reputed to smoke two cigarettes at a time. The rest of us landed cautiously. I found that my smoothest landings were those made with a full bomb-load aboard.

On October 5th we went to Saarbrucken, but on the way home were diverted to Coltishall in Suffolk because of the weather. The Americans there turned out new beds and mattresses and gave us a meal of ham and peaches. We flew back to the delights of Kelstern the next morning.

On daylight raids, contrary to our lonely missions at night, we flew in a ‘gaggle’, confident of our fighter escort. The ‘gaggle’ was due to our lack of recent formation practice. Three aircraft from each group had brightly-painted rudders and other aircraft would formate as close as comfort dictated. Later, instructions were given that over the target the leaders would throttle back to merge with the ‘gaggle’, in order to reduce the risk from radar-guided flak. No crew were keen to be the aiming point for the German gunners and I remember an occasion at Cologne when the leaders reduced power but so did everybody, even lowering their wheels to keep station.

On the 7th we went off to attack Emmerich. It was a bright autumn day (my mother’s birthday) as we flew in a great ‘gaggle’ of some three hundred and fifty Lancasters towards the target. Over to starboard a similar force of Halifaxes was attacking Kleve, from which a huge column of smoke and dust arose. There are conflicting accounts for the reasons we went there. One states that both towns were on the route from which a German counter-attack against the flank of the Allied armies might come, although my recollection is that the garrisons were holding up the Allied advance. Suffice to say that the towns were left impassable. I was struck by the incongruity of the scene at 3pm on a sunny Saturday, at a time when people in England were going about their business, perhaps to a football match or the weekly shopping.

In the early hours of 14th October we were called from our beds at 0300 and briefed to attack the Thyssen steel works at Duisburg in the Ruhr. Watching Lloyd Hannah, a young Canadian pilot, ahead of me taking off, I took my turn on to the runway just as the dawn sky was ripped apart by a huge explosion and pyrotechnic display dead ahead. We knew immediately that he had gone in with his nine tons of bombs. Engine failure on take-off was the dread of any pilot. It was a successful attack but, as we left the target, the flak got our starboard inner engine and it had to be shut down.

At Kelstern we were briefed to go back to Duisburg that night, but this being a ‘maximum effort’ target, there were no spare aircraft. This clearly put the ground crew on their mettle. I understand they set a new record for a Rolls Royce Merlin engine change and we finally took off some time after the rest of the squadron.

I cannot remember details of this raid, perhaps because of the wealth of incident this day. Suffice to say that we were late back, and as we touched down, I was asked to clear the runway quickly as there was an aircraft in trouble behind me. It was a Wellington from a Polish squadron that crashed in flames on the runway, but with no casualties.

The ‘double Duisburg’, as it became known, was officially ‘Operation Hurricane’, an attempt to persuade the Nazis that their situation was hopeless. Over a thousand bombers took part in each raid, with other attacks by the US 8th Air Force during daylight.

These major night raids were quite complicated: Lincolnshire and the surrounding counties were a mass of airfields, some cheek by jowl. From most of these, other squadrons would be rising to join the bomber stream, whilst diversionary raids to mislead the enemy fighters would also be setting out. The intention was to overwhelm the defences by concentrating the attack with careful timing. Diversionary raids were mounted to ‘light up’ some of the defences en route. This guarded us from wandering into them and also gave a good navigational fix. Frankfurt was a case in point. It was frequently near our route and was very heavily defended by guns and searchlights, so a couple of squadrons of Mosquitos would attack it as we approached and we would alter course as the defences lit up.

It was the overall plan of the night’s operations that I think gave most of us the confidence that we were not just being sent ‘over the top’ without thought. Despite this we never referred to the C-in-C as ‘Bomber’ Harris as the newspapers did. He was always ‘Butch’ to us.

Personally, I never saw an enemy night fighter. Their presence was sometimes obvious from the lines of flares being dropped along the track of the bomber stream or the sudden bursting into flames of a neighbouring aircraft. Their tactic was to approach from the rear to the blind spot underneath the bomber, then open up with twin upward-firing cannon. They did not use tracer ammunition, so the method remained unknown to us for a long time.

Defence relied on the vigilance of Bob Job who, on sighting a night fighter, would warn me and initiate the ‘corkscrew’ at the moment he judged the fighter was committed to the attack. This was a violent evasive manoeuvre designed to shake off the fighter and leave us ultimately on the same heading. It was a great strain on a loaded bomber and upsetting for the crew who had to be warned at each change of direction.

Daylight raids were much preferred from our point of view. Firstly they were shorter, being limited at that stage by the range of the escort fighters, our guns being too puny to fight our way against mass fighter assault. There was the danger of ‘friendly’ bomb-loads from above, when some joker had sought extra insurance in the way of altitude. The sight of a four thousand-pound ‘cookie’ wobbling past or a string of thousand-pounders just missing the wing tip was not easily forgotten, but at night they fell unseen.

Collision was a real danger at night or in cloud. I remember setting out over Southend at dusk with an uneasy feeling about the proximity of others. Suddenly two aircraft ahead of us burst into flames and fell to earth. Immediately several hundred sets of navigation lights were switched on to reveal how near they were.

October drew to a close with a trip to Essen and three trips to Cologne, one in daylight where we picked up some flak damage.

November had some cold, clear nights and we were kept busy. On the 4th we went to Bochum, heavily defended by searchlights, flak and fighters. Seeing a Lancaster caught in a cone of searchlight beams is a terrible sight, matched by the numbers of aircraft falling in flames. It was here that my friend from Sandtoft, Taff Edwards, and his crew died. Claude Terriere, the navigator, was nineteen and had come from Mauritius to fight.

It is not easy to describe one’s feelings as the target drew near. Foremost was anxiety that you were in the right place at the right time; the coloured TIs going down in front of you hopefully solved this. If you were late then you were greeted by the twinkling of the flak barrage ahead. It would be natural to have a moment of sympathy for those about to receive the bombardment, but the situation was too tense for such luxuries and the realities of Nazi rule for the occupied countries meant that we had to strive for the earliest end to the bloodshed and grief.

Our main targets this month were oil-related, the weak point of the German economy. On the next two daylight jobs we were chosen as the leading squadron in the ‘gaggle’, the first was to the refinery at Gelsenkirchen. It was a fine day with scattered cloud and on the approach to the target an aircraft ahead began to trail smoke and flames from one engine. We soon overtook it and I told Jock Mackintosh to make a note of the squadron markings as it was not one of ours. Then the crew started to bale out; not easy from a Lancaster. I counted three leaving before it was lost to view under our starboard wing. The rear gunner saw no more go and it continued straight on, so presumably the pilot was still in control and sticking with it, as would be expected. In a Lancaster the escape hatch was a smallish round hole under the nose, easily accessible for the bombaimer and engineer in a panic situation, less so for the navigator and wireless operator back by the main spar, and difficult for the mid-upper gunner in his turret, or the pilot encumbered by his seat parachute. The rear gunner could exit, if he got the order, by rotating his turret and falling backwards. Post-war analysis showed that on average fewer than two out of seven aircrew escaped from a Lancaster.

Three days later we went to the refinery at Wanne Eikel in daylight, again being lead squadron. There was complete cloud cover and it felt lonely out front but I was pleased to notice Clem Koder in ‘G for George’ alongside on the bomb run. When we got through the target there was no one in sight, but this was normal as the tendency was to hightail for home.

On 11th November we went to the oil refinery at Dortmund and I had to take a new crew. The system had changed since I did my ‘second dickie’ trip. Instead of just the pilot, I had to take the whole crew apart from the navigator and rear gunner, so it was reassuring to have Gordon and Bob Job with me. I was not overjoyed at the prospect, as an operational tour then required each crew member completing thirty ‘ops’. If somebody was not on the Battle Order, it behoved the crew to bring him up to scratch by doing extra trips. I don’t think anybody liked flying with strangers; your ear got attuned to the comfort of familiar voices on the intercom. But the night went well.

One daylight operation was against Duren on the 16th, one of three towns holding up the advance of the American First Army. They were all destroyed. We were bombing from a medium level and I had the impression of an aircraft blowing up in front of us just as I received a blow on the head, leaving me momentarily dazed and disorientated. We were still on the bombing run with some loads falling past us, so as soon as we had ‘bombs away’, we took stock of the situation. The offending object was a bomb pistol that had shattered the thick plexiglass cockpit canopy and bounced off my helmeted head to land beside the engineer.

Fortunately, it was made of aluminium or it would have been the end. Such safety devices were fitted to a bomb to make it ‘live’ after it had fallen a set distance, a small propeller unwinding as the bomb fell. Either it had been dropped from well above or it may have come from an exploding aircraft. In this respect, we had been told, and firmly believed, that the Germans fired ‘Scarecrow’ rockets to simulate an aircraft blowing up. We had all seen them and they were quite unnerving, but after the war the Germans denied using any such tactics. I had the bomb pistol until 2005 when I presented it to the War Heritage Museum at Mount Hope.

On the night of 18th November we were again attacking the refinery at Wanne Eickel and I had another inexperienced crew doing a ‘second dickie’. The weather was bad, we bombed on a glimpse of the target indicators and then we were back into the thick cloud and turning for home. Suddenly a dazzling white light reflected by the surrounding cloud illuminated us. The Bomb Aimer was using the Aldis lamp to check for hang-ups. Not a good idea at that point and my oaths reflected my unease. The Wireless Operator then advised that we had been diverted but he didn’t know to where. This was no problem whilst over Germany, but when we got over the North Sea it became more pressing and when I saw that we were gradually losing power, I decided to turn on the carburettor heat.

The Lancaster was a great aircraft with two things I didn’t like. The escape hatch being too small was the important one. A minor problem was that the carburettor heat control was behind the pilot’s seat adjacent to the similar fuel jettison control, which was wired shut. I picked the wrong one and the pungent smell of the high-octane petrol being dumped made me correct my mishandling at once.

By now the wireless operator had worked out that the diversion was to Knettishall in East Anglia, an American Flying Fortress base and an excellent choice. I knew from experience that they would give us clean bedding, a slap-up meal and the liquor would run free. I was not disappointed. There was a bonus too, of sorts. When we appeared at late breakfast, unshaven and shabby, we joined about a hundred good-looking English girls who were staying overnight for a Mess party. Kelstern was never like that: we were grateful there for a relieved welcome and a tot of rum.

At an American base there was always the danger that the pilots and navigators would be taken by coach through the fog for a couple of hours to where Intelligence Officers could comfortably hold the de-briefing. It happened. Being diverted to another RAF base was worse. It would probably be suggested that you look in the huts for the bed of somebody on leave.

Anyway, the Knettishall Mess invited us to their party, but after watching a Bob Hope film, ‘Thanks for the Memory’, the expected recall to Kelstern came through. Particularly impressive to my eyes was that every man on this US Base had a fleece-lined, leather Irving jacket. In the RAF such items were rare amongst bomber crews by this stage of the war November 1944 closed with a ‘gaggle’ to Dortmund when the flak got our range and several were wounded, including Sandy Lane and Dave Mattingley, the quiet Australian.

The long mid-winter nights were now upon us: more darkness meant more distant targets. I carried two bottles: one personal, the other full of de-icing fluid, in an attempt to maintain a peephole in the ice that covered the inside of the windscreen at altitude. Neither worked.

We set out to breach the Urft Dam near Heimbach on 3rd December, but cloud hid the target and we brought our bombs back. American troops waiting to advance were in peril if the enemy released the water while they were attacking. It was raided and damaged the next day, but the Germans kept control for some time.

On the 15th we were sent to Mannheim-Ludwigshaven where IG.Farben had two important plants. Dusk had fallen by the time we were over the Netherlands, when a sudden flare on the ground caught my eye. In seconds it began to rise and rapidly accelerated past us trailing smoke or steam until it disappeared in the clear sky above. It was my first and only sight of the V2, the second terror weapon that Hitler had promised. They had been falling on London with great effect for some nights. The government did not explain until much later what the huge explosions followed by the roar of the rocket, which I’d heard when on leave, meant. This added to the mystery.

Due to unexpected winds we got to the target early and I told the crew that we would do a circuit to come in at the correct minute and heading. This evoked a cry from the substitute rear gunner who suggested that we go home. I put out of my mind the three hundred or so other aircraft which might also be circling, but as we turned on to the correct bomb run, the TIs went down.

It was a very successful attack particularly on IG.Farben. Sadly, Pilot Officer Fletcher, who I’d taken to the Dortmund Refinery about a month before, was shot down and killed with all his crew. A quiet, married man who had just been promoted, he was twenty-eight with a crew of twenty year olds.

During a spell of leave I went to the Harrow Road to see the parents of Bernard Edinborough (ex-Mount Hope) who was flying obsolete Stirlings on operations. Unfortunately, my call coincided with the delivery of a telegram to say that he was missing. I found out later that he had been dropping guns and supplies at low level to the Maquis when he was hit and crash landed. He was hidden by them in a wine cellar for six weeks, then escorted by a flamboyant character in riding breeches and boots to Paris, and then down the line to the Pyrenees and Spain.

On December 17th the target was Ulm, which meant another trip of eight hours plus. At briefing, we were cautioned to avoid the highest church spire in Europe. We were bombing from eleven thousand feet, which meant that we had a good view of the target and the fires that ensued. About this time Gordon was commissioned to Pilot Officer.

On the 21st, Bonn was the objective, from where we diverted to Sturgate. This airfield was still in Lincolnshire but had been fitted with FIDO (fog investigation and dispersal operation) a fog dispersal system that used a line of oil burners either side of the runway to make a clear tunnel through the fog. This was a real lifesaver, the reflected glow of which could be seen from a great distance. It compensated partly for the withdrawal of the blind landing system.

The fog and snow persisted for several days, preventing any flying from intervening against enemy tanks that had broken through the Allied lines towards Antwerp and Brussels. This was the Battle of the Bulge. We had to wait until Christmas Eve to recover our own aircraft from Sturgate, when we used FIDO for take-off to return to base.

It was Christmas morning, I think, when, drawn by the noise, we rushed out of our Nissen huts to see two V1 doodlebugs about two hundred feet above our runway heading West, probably meant for Sheffield, Manchester or Liverpool. They had been launched from a Heinkel over the North Sea. The Germans had sometimes sent Heinkels to observe our mustering and Junker 88 ‘intruder’ night fighters to intervene in our landing pattern, with some success.

On Boxing Day we were called early from our beds. The weather had cleared and we went to attack the SS Panzer Division at St. Vith. The ground was snow-covered and the target clearly visible at the curve of the railway, so the bombing was concentrated. From this point the German advance was stalled due to the resistance of the soldiers on the ground and the armoured columns running out of fuel.

The following day I was detailed to take fifteen aircrew (skeleton crews) over to Fiskerton for a FIDO landing to recover some aircraft stranded there. They had been refuelled and bombed up so the weight was high for a return. Once the snow had been cleaned off we set out and my landing was naturally smooth. We had a commendation from the Base Commander at Binbrook for this and I got three days rest in the sick quarters because our CO thought I looked ‘peaky’, but I was confident it was the Christmas beer.

The New Year saw us going to Nuremburg on the night of the 2nd. This was the scene of a Bomber Command disaster some months previously, but on this occasion things went well. The weather was good, and although the rising moon illuminated the contrails we left, which would normally cause concern, the use of Mosquito fighters, code-named Serrate, weaving through the bomber stream, was a great comfort. They were at great risk to themselves from nervous air-gunners. One Mosquito flashed across our nose, too close for comfort to my mind.

It was a different story on January 14th when we went to the refinery at MersebergLeuna. The weather was grim and so were the flak and fighters. This was a trip of nearly nine hours and it seemed particularly cold, with condensation putting a film of ice over the side windows and inside the windscreen. Bert Hazell, a quiet, twenty-four year-old Londoner, and his crew, were killed this night.

At last we came to my thirty-third trip, with all the crew having done at least the regulation thirty. It was to the oil refinery at Zeitz. I don’t remember a lot about it except that it was a very black night and we were doubly glad to return to the English coast. Another force of Lancasters went to Brux in Western Czechoslovakia, a longer trip. They only lost one aircraft but I learned later that it was my friend, Jock McGonigal with all his crew. Probably he had finished the magic number as well.

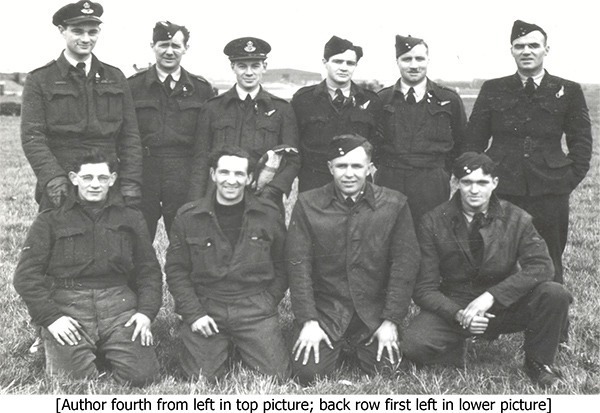

I threw a dinner at our usual Louth pub for the crew and the ground staff who had looked after us so well. We had our photograph taken in front of the aircraft, but Bob Job was absent from the photocall for some reason I forget.

We went on leave, the crew were disbanded and posted elsewhere. Gordon and I had applied together for Transport Command and were pleased to be posted to Canada (via Morecambe, to wait for a ship). We were happy until we boarded SS. Louis Pasteur and realized that all those new Sergeant Air Gunners who had been saluting us feverishly along Morecambe promenade were on the same draft. Why did they need them in transport aircraft?

We had a cargo of German prisoners heading for safety in a Canadian camp. They were an ingenious group and among the souvenirs they peddled was a plentiful supply of fake Iron Crosses.

We arrived at Moncton on April Fools’ day 1945. Gordon and I took a fortnight’s leave in Boston, Massachusetts, where we were made to feel very much at home by local families and by the British Officers’ Club formed by veterans of the previous war. Then we had to proceed via Montreal and Winnipeg to Boundary Bay, near Vancouver. Here we picked up two wireless operators, Flying Officer Basil Harrington and Warrant Officer Joe Sharp. A Flight Engineer, Bomb Aimer, O’Reilly Sykes, and a new second pilot, an exDundee policeman, Jock Brown. The engineer was an ex-London bobby who proved too tall for the turret and was shipped home, to my chagrin. The airport was on the foreshore and we learned to operate the B25 Mitchell, a powerful American twin-engine medium bomber with a tricycle undercarriage that was like having your own sports car, a delight to fly.

The country to the north was unmapped at that time, wild and mountainous. We went looking for a missing aircraft with no luck and heard later that ground parties had found almost a dozen that had been lost for years. There were two sights that are well remembered: the forest fires and the great rafts of logs being towed by tiny tugs. I had some friends visiting Vancouver Island so took the ferry to Nanaimo and was rewarded by the sight of Finnish-owned ‘Passat’, one of the last four-masted clippers.

VE day arrived which meant a wild night in Vancouver. Somehow I finished up on a tugboat in the harbour among friends.

We learned that we were destined for the Far East, the next stage being a move to Abbotsford, some way inland, with Mount Baker looming in the distance. Here five gunners joined the crew, two of them being experienced men: Warrant Officers Cooper and Rees, and Sergeants Benton, Beale and Herbert.

We flew Liberator B24 heavy bombers, very different in our experience. The USA was turning them out at the rate of one per hour. They were seriously armed with ten heavy machine guns in four turrets (Sgt Herbert had to be squeezed into the Ball Turret underneath) and open waist-hatches. They carried a bomb-load that was small to our eyes. One feature was a very thin wing, the tips of which only became visible to the pilot when they rose into view on take-off. It was a complicated aircraft, and having no engineer, I made it my business to learn every detail.

The reliable engines had an excellent supercharging system that enabled a climb to 30,000 feet. We only approached that height on one night flight over the Rockies when fire broke out in the radio room, just behind the pilots. Time stood still while Warrant Officer Joe Sharp fought and extinguished the fire that melted the radio. The senior radio officer had fled the scene and was buckling on his parachute.

Our time was spent practising formation tactics against fighters supplied by a local squadron. There were longer flights over the Pacific and a great deal of high- and lowlevel bombing on the range.

There was a regrettable incident when our Bomb Aimer, more used to a sophisticated British system, left a neat row of craters across the estate of a citizen living near the bombing range. We both had to appear before the CO for that, but our explanation was accepted.

We finished the course a few days before the atom bombs were dropped in Japan, to our great relief, which meant that our flight from Montreal to the Far East was cancelled, and we proceeded via Moncton and SS. Niew Amsterdam to Southampton.

When we sailed from New York the banners read ‘Welcome to our American boys’, and at Southampton they said ‘Farewell to our American friends’.

Transport Command

After a month swanning around Harrogate, Gordon and I went to Full Sutton (now a high-security prison) where 231 Squadron was being formed as a round-the-world, highspeed VIP transport unit equipped with Lancastrians, ie a Lancaster sans turrets, but with a cabin and nine sideways-facing seats, plus a long-range fuel tank. Not a very practical aircraft to compete against the Douglas DC4 etc, but the Marshall Plan was finished now and we were in a competitive environment.

All the aircrew on 231 were highly experienced, most had completed at least one tour of operations. For recreation, York was nearby and we often went there for an evening without booking a room, relying on getting a bed for the night by turning up at Mrs P’s, a lodging house of many rooms. This kind and generous lady left the door on the latch and a table laid with excellent baked goods for those needing food. There were sometimes a dozen or more of us at breakfast where the menu was bacon and eggs. The total charge was five shillings.

There were hilarious evenings. One two-tour wireless operator had been invited by friends to share their room in a well-known temperance hotel. Arriving there after closing hours, he staggered to a room and took off his shoes and trousers, only to be jarred by a scream from the young lady occupying the bed. Grabbing his clothes, he fled down the corridor to be hauled into the correct room by his friends. There was an official complaint to the CO and all navigators, wireless operators and flight engineers were paraded. The young lady remembered seeing a single wing brevet on the officer’s tunic, so pilots were excused. Nobody owned up until the CO threatened to confine all those on parade to camp until the culprit came forward. Later he did and I believe it was settled by a profound apology.

After retraining on the tail-draggers and various radar courses, sanity intruded and the squadron was disbanded. Some, I read, went to the newly-formed British South American airline under D. C. T. Bennett. We proceeded to Stradishall, near Cambridge, to 51 Squadron, for conversion to the Avro York.

The York was a more practical adaptation of the Lancaster. The high wing allowed a roomy fuselage, enabling about thirty passengers to be seated or carriage of mail and freight. The absence of a pressurized cabin and lack of oxygen for passengers meant that there was no prospect of climbing above rough weather, so sick bags were a necessity.

This was a good time from May to August 1946: we had an objective in view, the training was interesting and the delights of Cambridge were close. It culminated in a trip to India via Holmsley South. My old friend Bernard Edinborough of the Harrow Road was there on Transport Command, and we decided to visit a pub in the New Forest on his motorcycle. Unfortunately, he had to proceed in low gear to keep the lights on and we ran out of petrol on the way back. Faced with a long walk on a lonely and dark road, I was amazed when a lady driver stopped and agreed to sell a gallon from her ‘ration’ (at 400% profit). The sight of her pouring petrol from the can to the tank with a lighted cigarette between her lips caused me to retreat hastily.

We left Holmsley South for Castel Benito in Tripolitania, thence Cairo, Basrah, and down the Persian Gulf, when we were warned of storms at Karachi and put down at Jiwani on the Baluchistan coast. I still harbour the suspicion that they over-egged the forecast to persuade us to land. On a previous occasion they apparently had a welcome complement of service nurses arrive. We only had a load of diplomatic mail. I could sympathise. The landscape was uniformly grey and the fresh water had to be flown in every week. The bathwater was more than brackish. In the Mess, we were made very welcome, but beer was limited to one bottle per head. Unlimited spirits were available, but there were no mixers. It must have been the worst ever posting – Shaibah in Iraq, with its trees of camouflage netting, was heavenly in comparison. No wonder that the great Alexander pressed on. The evening was brightened by the presence of the wife of a chap flying to Australia in a small aircraft. We were flying the Empire Air Route, where in those days every base was British-controlled, by force of arms where necessary.

On this leg of the journey we would often see great fleets of sailing craft running up to the Gulf: Kuwaiti Booms (modelled on the first Portuguese sailing ships to penetrate there) and sleek schooners.

Britain was still in control of India and we took the balance of our mail to Delhi where I made a point of calling on the Station Warrant Officer who, according to Bernard Edinborough, was the same martinet who had harried us new sergeants at Mount Hope. I wanted him to know that he was not forgotten, so we exchanged pleasantries.

After a magnificent curry we returned to find the aircraft almost untenable from standing on the Palam concrete in the noonday sun. I decided to do the take-off stripped to my underpants and get dressed at a cooler altitude. By the time we got to 6000 feet, I was back in my kit and seated when a gaggle of dots materialized dead ahead. I just had time to duck below the windscreen level when they hit us, fortunately on the wing tip, which had a two-inch dent and a smear of blood. I presume they were kite hawks, although surprised at their altitude. The whole trip took nine days, retaining the same aircraft.

In August 1946 we arrived at Lyneham, near Swindon to join 511 Squadron which was running regular services to Cairo, Delhi and Singapore. The co-pilot and the radio officer outranked me, which might have been awkward, but with Gordon as navigator, we all got on well together.

I was detailed to go as co-pilot to Singapore with a senior pilot who was being demobbed on return. It was a chance to observe things without the ultimate responsibility. All pilots had been asked to extend their service to assist the repatriation of troops from the East and I had signed on for another eighteen months beyond my demob date. It was a pleasant trip. We were staging, which meant that after two legs of the journey, we stayed overnight, but the aircraft went on. We then took the next aircraft.