Service Numbers: 436106

Enlisted: 7 November 1942, Perth Western Australia Australia

Last Rank: Flying Officer

Last Unit: No. 153 Squadron (RAF)

Born: Kalgoorlie Western Australia Australia, 16 April 1916

Home Town: Port Adelaide, Port Adelaide Enfield, South Australia

Schooling: Christian Brothers College Wakefield Street Adelaide

Occupation: Police Officer, Public Servant

Died: Natural Causes, Scampton England United Kingdom, 7 May 1991, aged 75 years

Cemetery: Not yet discovered

Memorials:

World War 2 Service:

7 Nov 1942: Leading Aircraftman, Empire Air Training Scheme

23 Jul 1943: Sergeant, Empire Air Training Scheme

1 Oct 1944: Flying Officer, No. 153 Squadron (RAF), Air War NW Europe 1939-45

Biography

Flying Officer Thomas (‘Tom’) Patrick TOBIN, RAAF

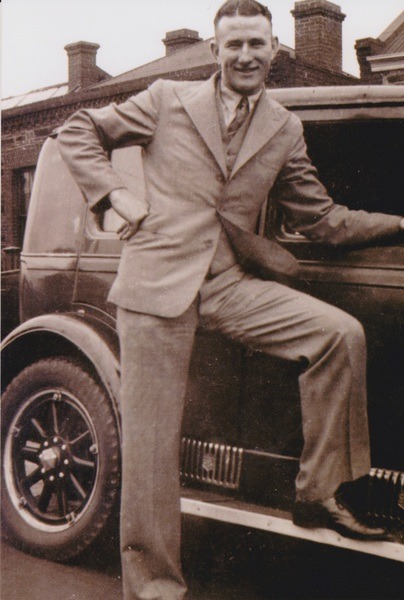

Tom Tobin was born in Boulder City on the Western Australian goldfields on the 16th April 1916. He moved with his family to Ceduna on the West Coast of SA.

He went to school at Christian Brothers College in Adelaide, leaving at the height of the Depression and returning to the West Coast.

He was 15 years old and living in Ceduna working in Irwin Brothers Grocery store when Jimmy Mollison flew over Ceduna during a round-Australia flight. Tom was on a half day off on a Friday and saw Mollison throw something from his aircraft. It was a rolled up Advertiser newspaper with a request for someone to call Adelaide and advise Mollison’s ETA there. An excited Tom Tobin ran to the Post Office with his message. The Post Master promised to relay the message to Adelaide. Thus began Tom’s desire to fly.

He had applied to join the SA Police as a cadet, and in due course was accepted. He recalls in his memoirs that the cadet scheme was ‘akin to slave labour’ as they were paid very little and required to perform duties pretty much as per those of a sworn officer. The arrangement was that they would be duly attested on attainment of the age of 21.

Tom recalled that he spent most of his pre-war police service in Port towns; Port Pirie, Port Lincoln and Port Adelaide. He was an accomplished boxer by this time and dealing with intoxicated merchant seaman in his various postings figures strongly in his recollections. “Sailing Ships were still common and most of the crews were Swedes and Norwegians. Sober they were no trouble but after months at sea they made the most of their shore leave and influenced by liquor they could be troublesome”. After being involved in a tense stand-off with enraged sailors after one of their number had been locked up, Tom was left to ponder what might have happened. “However the local people were very law abiding so mainly my stay at Port Lincoln was a happy one. The scrapes with the sailors must have tuned me up because when I arrived in Port Adelaide, I won the Police Heavyweight Boxing title.”

In fact he won the Heavyweight boxing title three years iin succession; 1938, 1939 and 1940. The Championship belt is in the SA Police Headquarters building in Wakefield Street to this day.

When war broke out, Tom was stationed at Port Adelaide. He sought permission to enlist in the RAAF, and then began a long and torturous process to do so. Police officers were classified as a ‘protected occupation’, governed by the Man Power Act. He had managed to get offside with the Police Commissioner, the legendary Brigadier Ray Leane (/explore/people/378781), a hero of WW 1. Ray Leane had allowed his own sons to enlist, but not Police Constable Tom Tobin, nor his brother Steve. Tom was therefore unable to enlist – at least in South Australia. Tom eventually ‘went AWL’ from the SA Police and went to Perth in his native Western Australia in order to enlist in the RAAF. He only just managed to evade a warrant for his apprehension, issued by the SA Police. His brother Steve remained in SA and stayed in his role as a police officer, eventually rising to the rank of Assistant Commissioner. Tom, however, was now on a different trajectory.

Thanks to a sympathetic Recruiting Officer and an official in the Man Power Branch, Tom managed to slip through the cracks and on the 7th November 1942, he was enlisted into the RAAF.

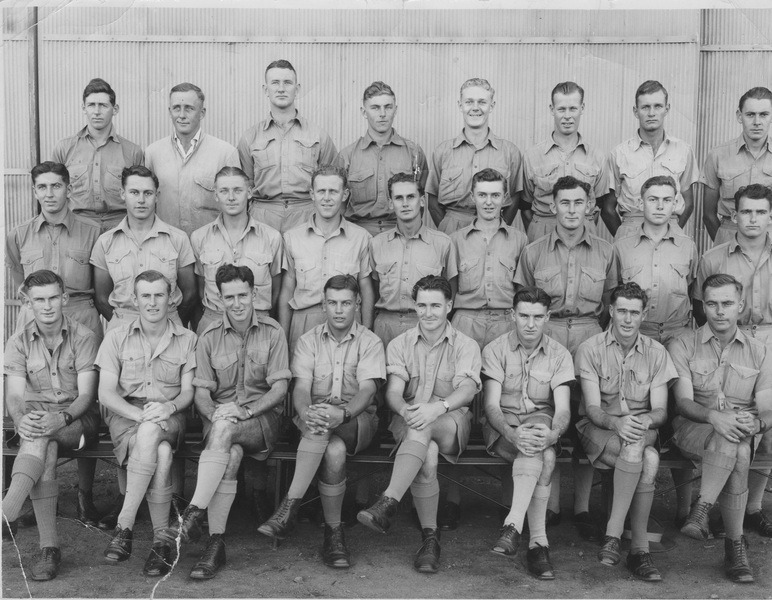

He was initially selected for pilot training and with the rank of Leading Aircraftsman, was posted to No 9 Elementary Flying Training School at Cunderdin in WA, No 33 Course. Here he learned to fly on DH 82 Tiger Moth aircraft from Feb 12 1943. He flew his first solo sortie on 23 March 1943, a signature point in every pilot’s career. By 7 April 1943 he had accumulated 57 hours of which 26 were solo, and 3 hours of night flying. He was rated an ‘Average’ pilot. during basic flying training. He was assigned to 4 Service Flying Training School, at Geraldton in WA, having been selected for multi-engine training on the Avro Anson. By the end of July 1943, he had accumulated 194 hours flying time. His rating of Good Average in bombing probably set in train the next course of events.

During this time, on the 5th July 1943 in the middle of winter, he was involved in an incident in an Anson, flying as second pilot on a cross country night navigation flight. Bad weather engulfed their aircraft and he and his colleague began debating their options. They eventually spotted a rail car through the gloom which had stopped with its headlight on, realising they were in trouble. There was a cleared paddock adjacent to the rail lines and Tom took control of the aircraft and put it down in a ploughed field, wheels up. It turned out they landed in one of a very few suitable spots for miles around with only 12 gallons of fuel left in the tank. The Anson was repaired in situ and flown out some days later.

On the 27th July 1943, Tom Tobin was awarded his wings and promoted to Sergeant.

After a short period of pre-embarkation leave, he embarked on the 30 August 1943 on the SS America, a fast liner of 35,000 tons. Their destination was the USA running unescorted to San Francisco. From there, travelling by train from West to East they took in the scenery in relative comfort. A brief stay of leave in Boston enabled him to make acquaintance with three aunts who lived near Bangor.

On the 3rd of October 1943 then boarded the SS Aquitania to cross the Atlantic, zig zagging to avoid German U Boats..

In the UK at No 29 EFTS it was back to basics albeit at an Advanced Flying School where he was once again flying the DH82 Tiger Moth. Then it was on to RAF Croughton and conversion and training on a series of training aircraft including the twin-engine Airspeed Oxfords and an emphasis on navigation and night flying operations. By the end of May 1944 it was on to the next stage – conversion to the Vickers Wellington twin-engine medium bomber. This was followed by the four-engine Handley Page Halifax bomber at the Heavy Conversion Unit Sandtoft.

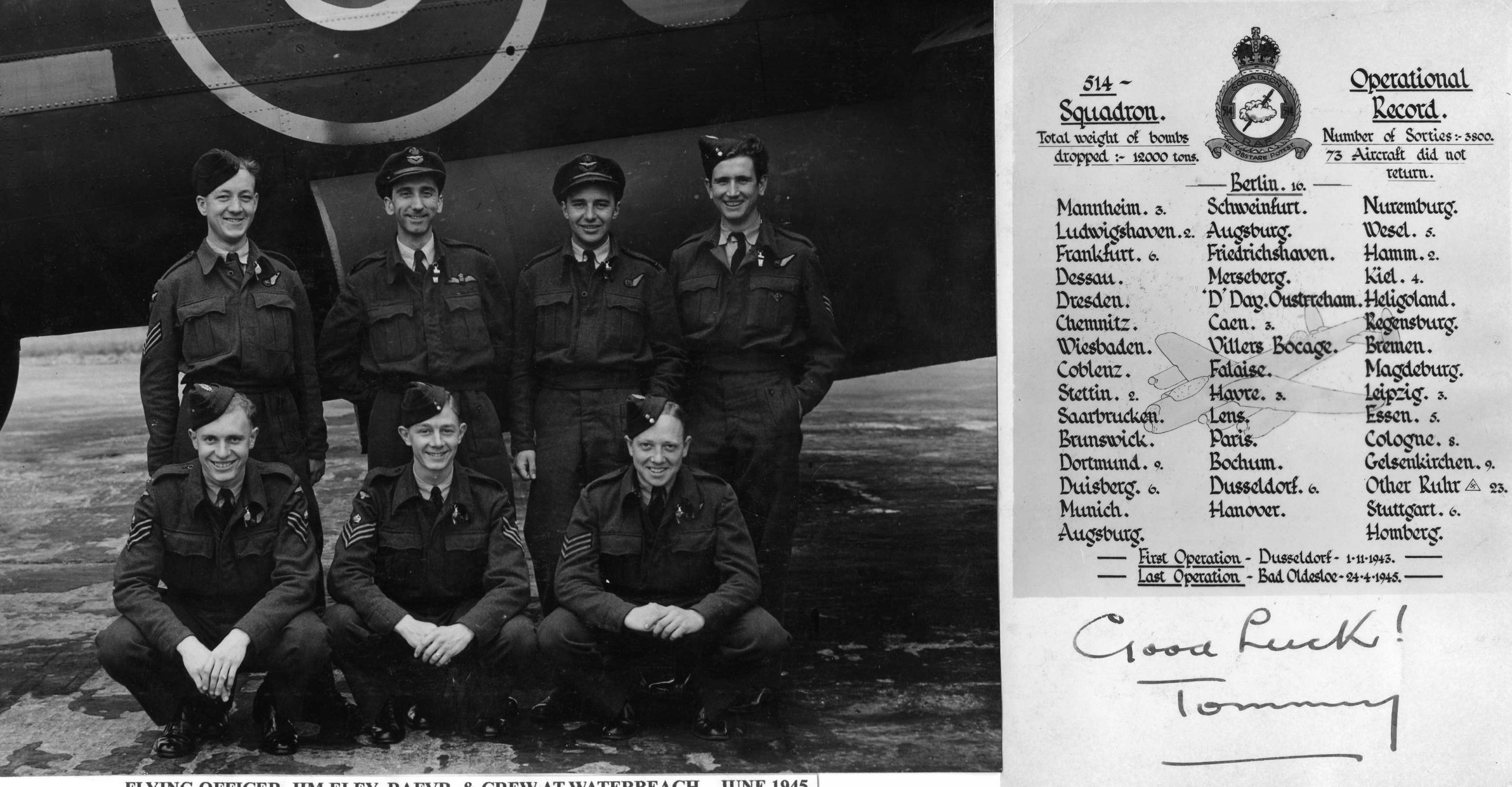

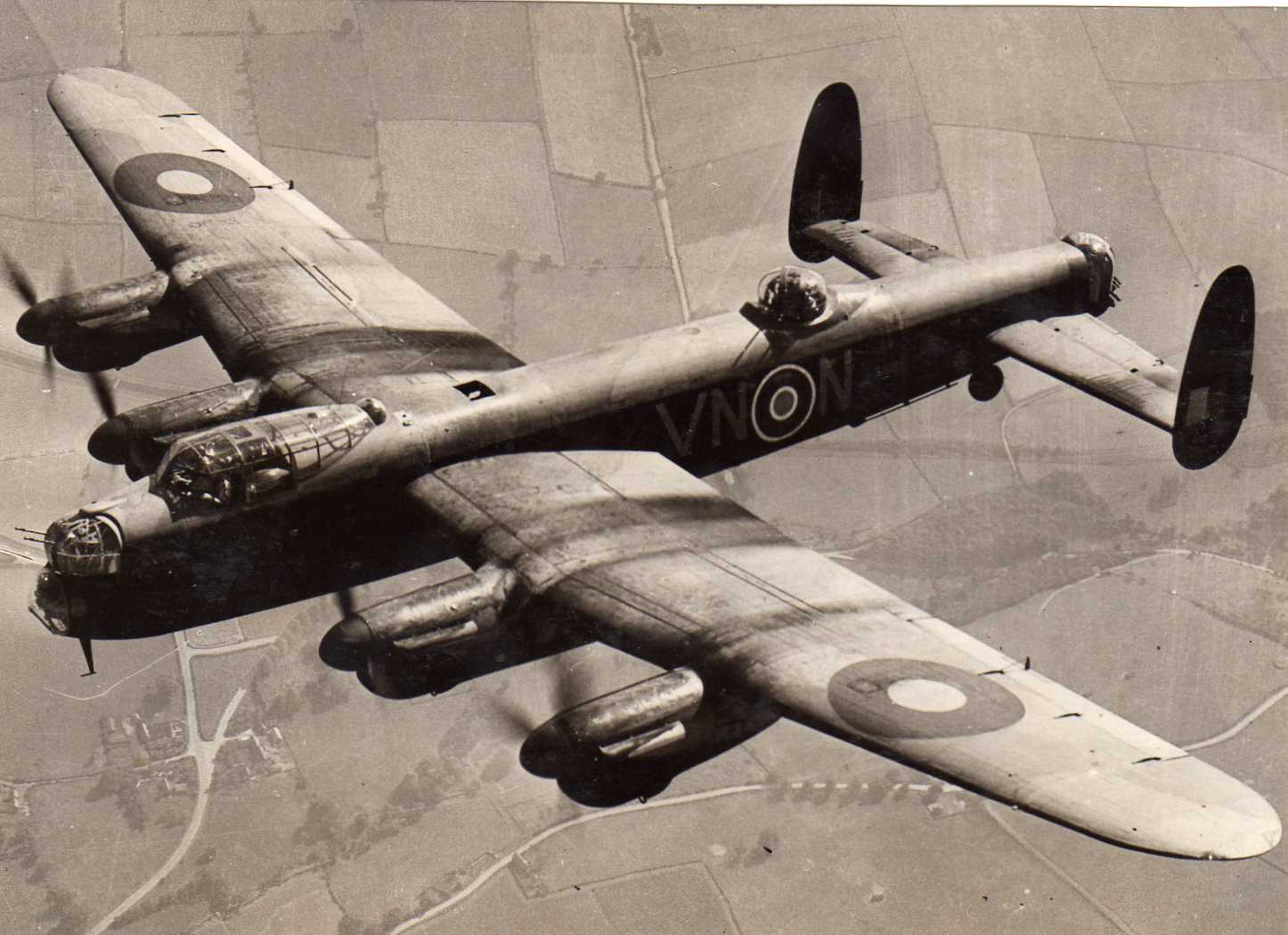

Tom was posted to 153 Squadron RAF which had formerly been a night fighter squadron, but was being reformed as a Heavy Bomber squadron equipped with the legendary Avro Lancaster. Like most RAF Squadrons at the time, its composition reflected the diversity of nations in the British Empire, with Australians, Canadians and other Commonwealth nationalities in its ranks. Tom was among the first aircrew and relatively few Australians to join the squadron when it reformed in October 1944, equipped with Lancaster Mk III heavy bombers.

He ‘crewed- up’ with the men with whom he would fly for the rest of the war.

– Tom Tobin (Aus) – Pilot

– F/Sgt Bob Muggleton (UK) – Bomb AimerF/Sgt Peter ‘ Paddy’ Tilson (NI) – Navigator

– F/Sgt Peter Rollason (Aus) – Wireless Operator

– F/Sgt Red Maloney (Can) – Mid Upper gunner

– Sgt Bill ‘Yorky’ Dolling (UK) – Rear gunner

– Sgt Peter ‘Jock’ Smart (Scot) – Flight Engineer

He flew his first familiarisation mission as a second pilot with another crew, to Essen. His log book then begins a pattern of recording the eventual fate of the tail numbers of each aircraft in which he flew. The first training flights he made with his crew were in aircraft that were subsequently lost. His log makes grim reading; a mid air collision, ‘did not return’, shot down by Ju 88 fighter attack (6 bailed out) and ‘wrecked’ accounting for the first four aircraft

Fourteen of his missions were flown in ‘W for Willie’ tail number 642. In an incident that goes someway to explain the reputation for superstition that characterised flight crews, on the evening of 16/17th March another crew took their aircraft while they were stood down. It was lost with all on board. They completed their tour in W1 RF 205, a replacement for their much loved W 642.

Tom and his crew went on to fly a full Tour of 30 operational missions with 153 Squadron, which are exquisitely described in his log book and a personal memoir. He and his crew completed their tour of duty just before the end of the war. He had accumulated 204 operational hours and another 56 hours training with 153 squadron, giving him a total of 705 hours 20 minutes flying time in all. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

His trials and tribulations with his employer, left behind when he went AWL from the SA Police in order to enlist, didn’t end there. On return to Australia, and resumption of duty with the SA Police, the award of his DFC was gazetted and he was scheduled to attend Government House in Adelaide for his investiture. However the SA Police would not grant him leave to do so. This resulted in a furore in the Press and Tom was duly granted leave. However not long after this Tom resigned from the SA Police and gained employment with the Commonwealth Department of Immigration, where he remained until his eventual retirement many years later.

After nearly 30 years, Tom began to pick up the threads of the contacts with his time with 153 Squadron. In 1972 he began actively seeking out his former colleagues and began travelling to do so. He also corresponded with former squadron crew mates and historians. He even corresponded with a German man researching one of the raids flown against his home town of Ludwighshafen on which Tom flew. He was active in the 153 Squadron association attending a number of reunions. It was on one of these in 1991 that he suffered a fatal heart attack.

Tom was an active member of the Royal Australian Air Force Association at Mitcham sub-branch. He figures strongly in the 153 Squadron website. At well over 6 feet tall he was not inconspicuous and was known by the nickname “Tiny” Tobin. He was survived by his wife Pat and only daughter Jane, her husband Denis and grandchildren Andrea and Heath. He is fondly remembered as a wonderful man and a ‘great bloke’.

His log book and memoir are a wonderful legacy. It has been my pleasure to write this up – these men were indeed part of the ‘greatest generation’.

Medals:

– Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC)

– France and Germany Star

– 1939-45 Star

– Defence Medal

– British War Medal 1939-45

– Australian War Medal 1939-45

Credit: Steve Larkins July 2013

The Dresden Raid February 1945

Tom Tobin’s 153 Squadron was part of what was to become, after the war, a controversial raid on the old city of Dresden. This is extracted from the 153 Squadron Website.

On 13th February, 15 aircraft were sent to Dresden. Although afterwards it became the subject of considerable and continuing debate, as far as the crews were concerned this was just another attack in aid of the Russian armies, on which (because of the distance involved), only a comparatively small bomb load could be carried.

Thus each crew took 1 x 2,000lb bomb plus 1,800 incendiaries. In clear weather and aided by gale force westerly winds, it took just over four hours to reach and bomb the target.

There could be no argument over the effectiveness of the attack – a massive firestorm (more intensive than that on Hamburg in 1943) swept the city, and could be seen from 100 miles by crews on their 650-mile homeward journeys.

They had plenty of time to watch, because there were now fighting against the same fearsome gales that had carried them so swiftly on the outward leg. Although benefiting from a much-reduced all-up weight, it took well over five hours of juggling of the fuel valves by anxious F/Engineers to struggle home.

Many made unscheduled landings to re-fuel: others reached Scampton with nearly dry tanks.

Nearly home but with fuel dangerously low Tom Tobin and his Flight Engineer Jock Smart shut down the two outer engines to conserve fuel. With no bombs and little fuel the Lancaster could easily fly on just two engines. So they feathered the props, and struggled on. On approaching Scampton and gaining a clearance to land he declined the instruction to complete the customary circuit and flew straight in to land – which was just as well, considering he was literally ‘running on empty’.

(A grim PostScript to mull over – of the 105-crew members from 153 Squadron who attacked Dresden and returned unscathed, only 66 survived the war – which finished just two months later. 39 died in subsequent operations)

Tom Tobin’s Log Book Report

Tom kept an exquisitely detailed log book of his flying career, together with memorabilia such as maps, photographs and the like.

His log book is now in the possession of his daughter, Jane. He recorded in great detail and in very fine neat hand writing every mission he flew.

He also kept track of the tail numbers of the aircraft he flew and their eventual fate. Lancaster 642 was the aircraft in which he flew most of his missions.

One evening in March 1945, he and his crew were due to fly but his navigator called in sick and rather than split the crew, they were stood down and another crew took 642. It didn’t return. No wonder flight crews had a reputation for being superstitious.

He is mentioned repeatedly in the 153 Squadron website as one of the characters (and survivors) of the Squadron.

At war’s end his grateful crew (he had brought them home safely 30 times) presented him with a beautiful scale replica of their aircraft. On its base is inscribed the targets of the 30 missions he ‘skippered’. It is now in the possession of his grandson Heath Eblen.

https://rslvirtualwarmemorial.org.au/explore/people/48546

*All information provided by Jane Eblen, Tom’s daughter.

Excuse me if I cry, but I will miss you as time goes by,

You suffered pain, but never complained,

Your conscience heavy because of many,

You flew 30 missions,

But returned with God’s permission,

And now your ashes shall be scattered alongside the great Lancaster

I could not say good bye, I love you Dad, Jane

According to my Dad’s wishes I spread his ashes on Scampton Airport in May 1991 accompanied by his brother Steve Tobin, the then Commissioner of Police in South Australia.