S/Ldr Kenneth George Bickers DFC

103 Squadron RAF Elsham Wolds

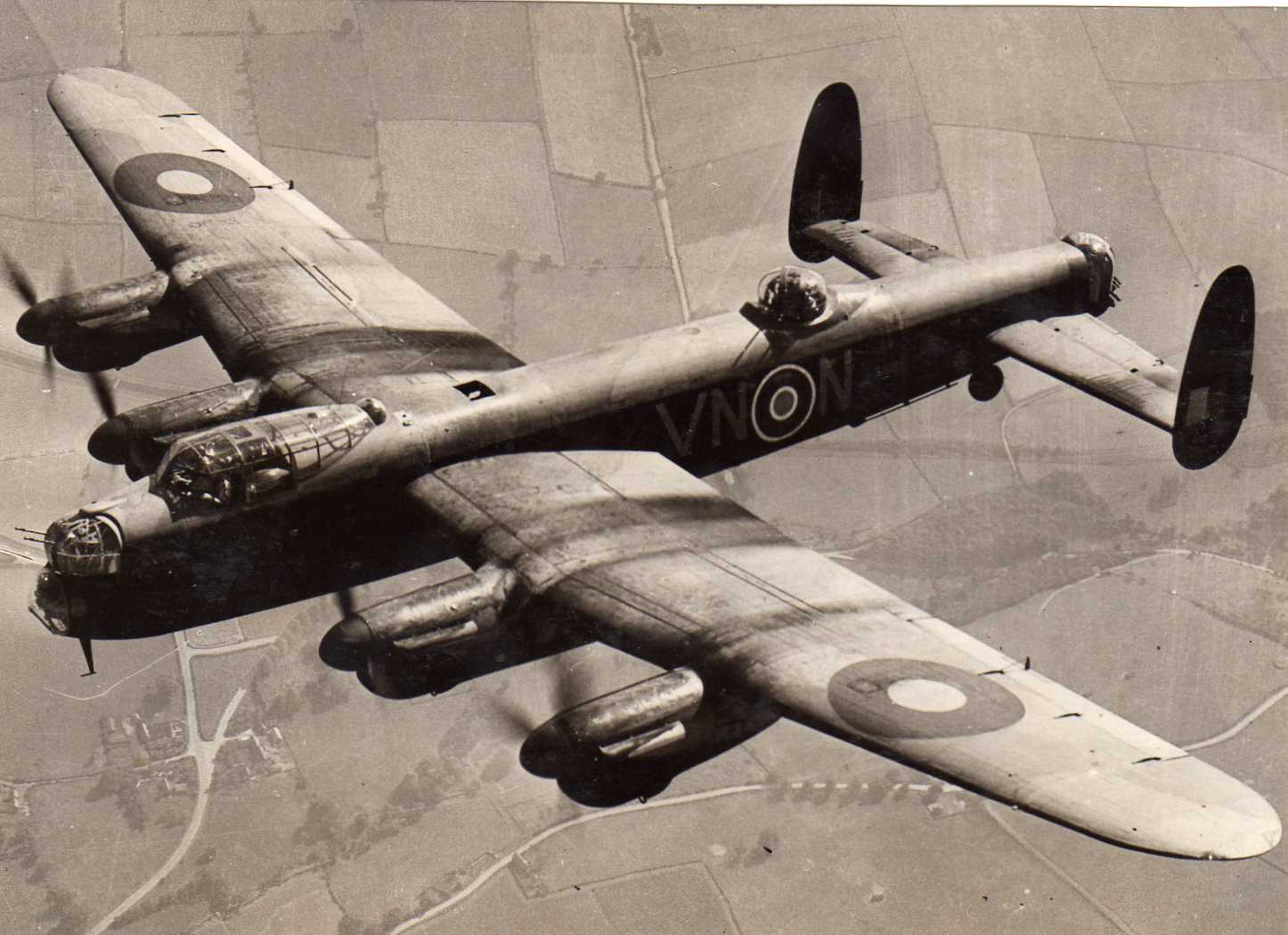

Avro Lancaster Bomber ME665 PM-C

(Lost night of 24/25 March 1944 over Berlin)

On 27 March 2015 we stood in a quiet field on the edge of a small forest near the village of Luckenwalde , about 30 kilometres south of Berlin , and placed a small wooden cross in memory of Kenneth Bickers and the six crew of his Lancaster who were shot down and killed on the night of 24/25 March 1944. Only three of the bodies were discovered, and they lie buried in the Berlin War Cemetery.

A Poppy Cross was placed on each Grave side in Respect. A very emotional moment in time.

To explain how my father and I came to be here with our new German friends exactly seventy-one years after that tragic event we need perhaps to explain Ken’s story. Ken was my Father’s brother, and we had come to try and find his final resting place.

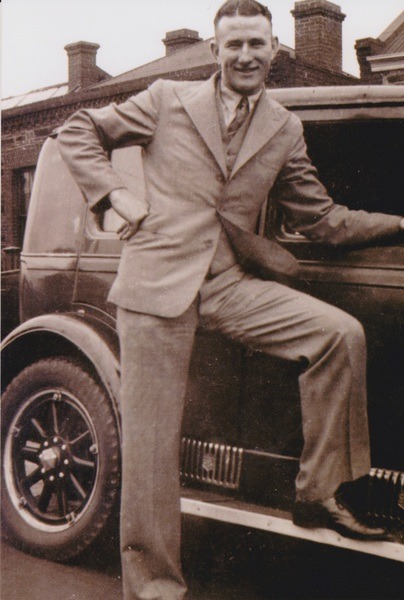

Kenneth Bickers grew up in Southampton in the West End district of the City, one of five children born to his parents James and Gertrude Bickers. Ken’s father James had run away to Argentina at the age of just fifteen, but returned in order to fight in the First World War – he survived but his brother Edward was not so lucky and was killed on the Somme just three months before the end of the war at the age of nineteen.

Ken’s father was a hard-working man who was not afraid to impose himself on his young family if the need arose, but he always did his best to provide and the family lived in a small rented semi-detached house not far from the centre of Southampton – however these were the Thirties in the years leading up to the Second World War, there was no bathroom, no inside toilet and no central heating, times were hard and about to become a lot harder.

Ken studied at Bitterne Park Boys School, was very popular amongst his peers, and rose to become Head Boy – in fact his Headmaster wrote of him ‘I cannot speak too highly of this boy’s character – he has been my Head Prefect for 18 months and has done excellently, he is self-reliant, steady and most reliable’.

The Second World War broke out when Ken was just seventeen, and he was keen to get involved. As he was under age for active service he joined the Royal Artillery and trained in mechanics and searchlight operations. A highlight came when he was commended and promoted to Corporal having taken control of a searchlight at the end of Hythe Pier in Southampton during the first Blitz in November 1940.

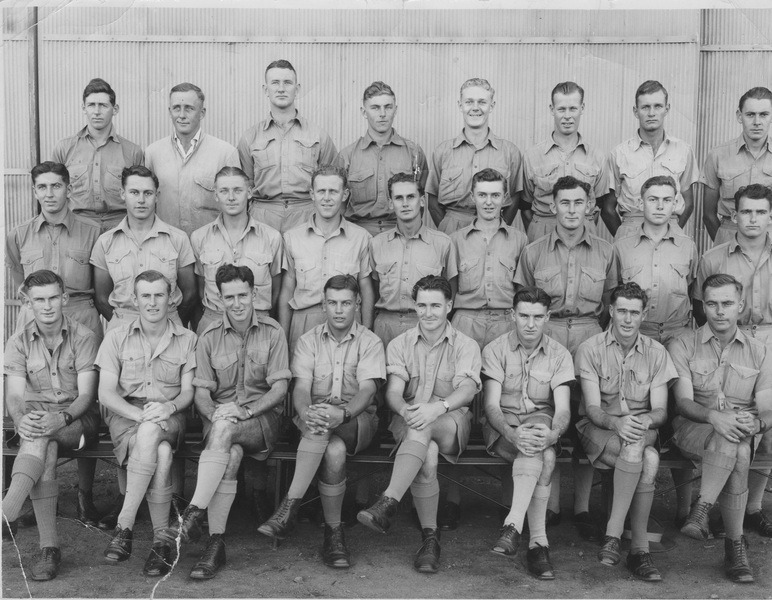

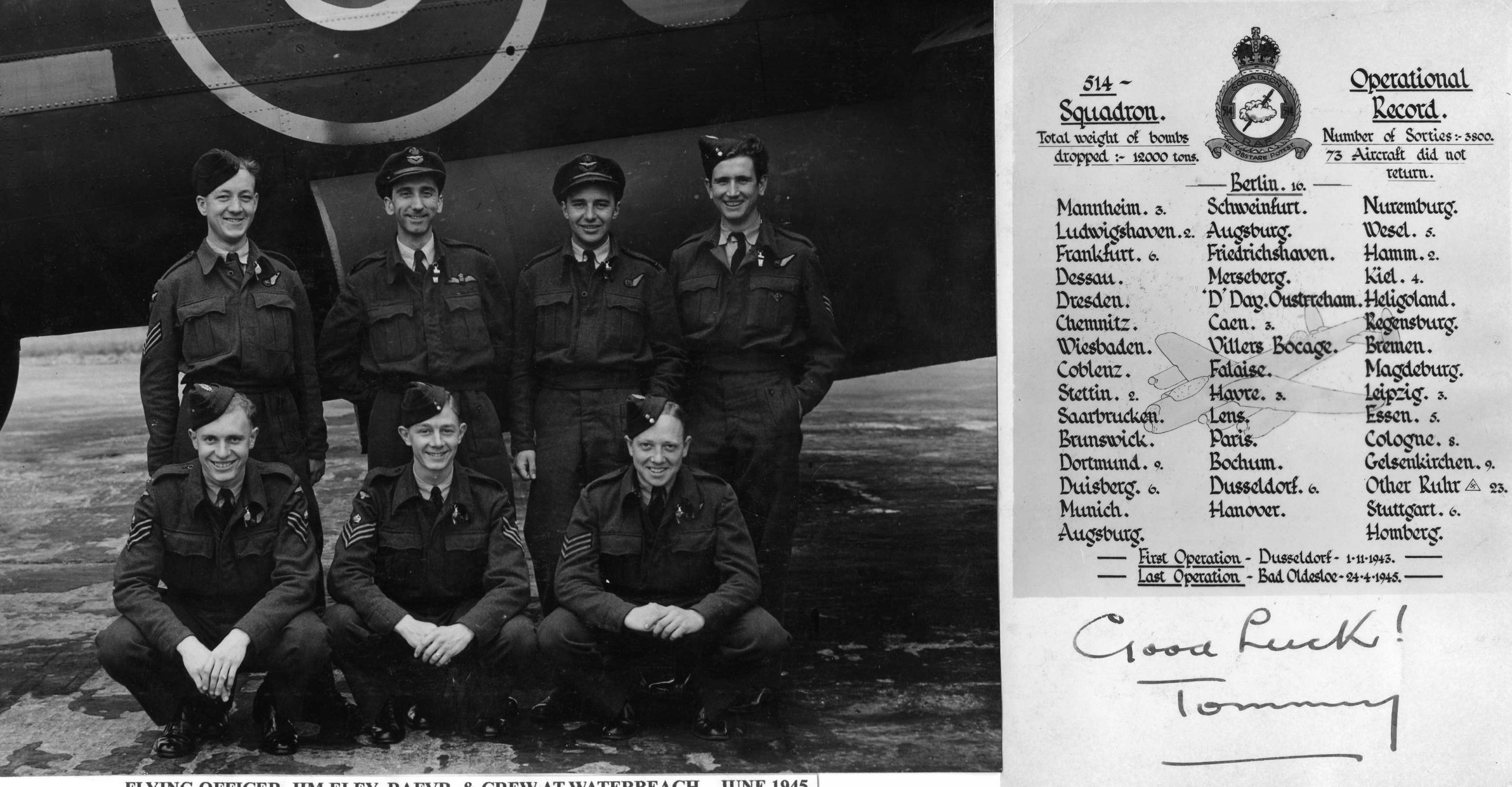

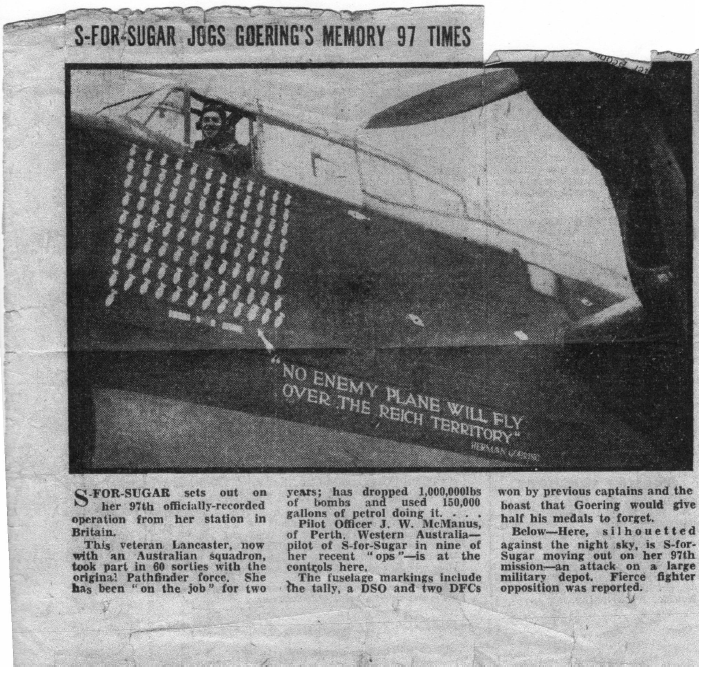

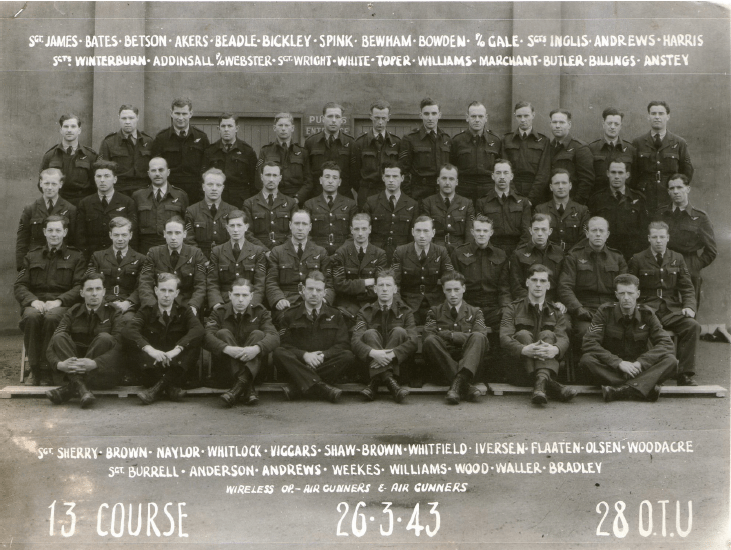

However Ken was not satisfied with being in the Royal Artillery, and decided that he wanted to join the RAF to make a more meaningful contribution, so he switched codes in 1941 and trained to be a pilot in Terrell , Texas , USA , returning to England after 6 months to complete his training and commence operations as a Pilot Officer in 1943. His first sortie from RAF Elsham Wolds with 103 Squadron was on 7 February 1943 attacking the German-held French port of Lorient, and by the beginning of April he had already flown 15 sorties attacking amongst others Wilhelmshaven, Nuremburg, Bremen, Cologne and Berlin.

In April 1943 Ken was awarded an immediate DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) – the entry in the London Gazette of 30 April 1943 describes Ken’s heroic actions on the night of 9 April:

‘One night in April 1943, Flight Lieutenant Bickers captained an aircraft detailed to attach Duisberg. During the homeward flight , whilst over enemy territory, the aircraft was attacked by an enemy fighter. The first burst of fire from the attacker killed the rear gunner, severely wounded the mid-upper gunner and set the rear turret on fire. For twenty minutes the enemy aircraft continued its attacks and only the skilful evading tactics employed by Flight Lieutenant Bickers prevented the bomber from being shot down. The elevator trimming gear was put out of action, the engine controls were damaged, the wireless apparatus and the hydraulic system were rendered unserviceable. Many instruments were destroyed while one of the port petrol tanks was pierced , causing its contents to leak away. In spite of the tremendous odds, Flight Lieutenant Bickers, displaying superb airmanship, flew the badly damaged aircraft to an airfield in this country where he effected a successful crash landing. In the face of a most perilous situation this officer displayed courage, skill and fortitude of a high order.’

Ken came to the end of his first tour of operations on 29 May 1943, having successfully completed 30 sorties over enemy territory in just under three months. He was still only 20 years old.

Whilst based near Leicester he had met a girl called Joan whom he had fallen for, and plans were made for them to get married on April 5 1944. In the meantime on 23 November 1943 Ken was accompanied by his parents and Joan to Buckingham Palace to receive his DFC from King George VI.

Once a pilot had completed a tour of operations there was no obligation to go back and put yourself in the front line again. It was considered that you ‘had done your bit’ and you were able to continue in service by training other aircrews.

However Ken decided to go back, in spite of his near miss as described above when attacked over Germany and despite being engaged to be married. It is not clear from the surviving papers why he took this decision, but reading between the lines it can be surmised that the ‘exhilaration’ of battle and the needs of the country triumphed over any regard for personal safety that may have given him pause for thought. There is a surviving letter written to his parents in February 1944 in which he writes:

‘..as soon as I received news that we were on our way back (to recommence attacks on Germany) I nipped smartly down to Leicester to see Joan – she’s still going to marry me at Easter and wouldn’t hear of any postponement. I’m glad!’

From this it is possible to gather that Ken was well aware of the risk he was taking, but the chance to do what he could for his country in its hour of need was the stronger pull, and tragically it would mean that he would not marry Joan as planned on 5 April.

Having moved around various air bases whilst doing further training Ken returned to RAF Elsham Wolds with 103 Squadron in February 1943. His surviving letters home are a mixture of describing the conditions under which he is living (‘..all my kit dirty and damp, the temperature is freezing, not a single clean handkerchief to my name..’) , and making plans for his forthcoming wedding to Joan (..’Joan gave me the job of deciding where to go on honeymoon, was supposed to have come to a decision last week but haven’t had a real opportunity to think’..).

A surviving letter written on 12 March to his parents indicates that although operations have not yet been recommenced he is expecting to go ‘any moment now’. He comments ‘I have a very good crew and a very good aircraft. The aircraft C Charlie is brand new, it took some wrangling, but we got it in the end!’ However it is also apparent that morale is low as Ken comments that ‘the squadron has completely changed, the old squadron spirit is almost entirely non-existent….we haven’t managed to make ourselves very popular….the Wing Commander and I don’t see eye to eye on a number of things..’

Ken, now newly promoted to Squadron Leader, recommenced bombing operations on Wednesday 15 March with an attack on Stuttgart – his logbook records it as a ‘quiet trip’. His last letter home was written on Friday 17 March – in it the preparations for his forthcoming marriage on 5 April are very much to the fore – he implores his Father to come to the wedding (..’how about taking some of your hard-earned summer holidays and coming along with Mum..’) and casually mentions his raid on Stuttgart (..’Twas a long stooge (sic) but an uneventful one for us – that’s how I like ’em !’). He ends the letter ‘…Well I think I had better close so cheerio for now. My love to Bunty (his small sister) and God Bless you all. Your loving Son , Ken.’

On Wednesday 22 March Ken’s logbook records a sortie to Frankfurt, again recorded as a ‘quiet trip’. There are no further entries.

Ken and his crew, F/O Plummer, F/O Tombs, F/O Bell, F/S Wadsworth, F/S Comer and F/S Cannon, took off on what was to be their final sortie on Friday 24 March 1944 to attack Berlin. The operation to Berlin on 24/25 March 1944 was the final raid of The Battle of Berlin and the last large-scale attack on the city by Bomber Command. Forty-four Lancasters and twenty eight Halifaxes were lost from the force, 8.9% of the total.

The official entry for Ken’s last flight appears in Bomber Command Losses, volume 5 1944, page 131 by William Chorley:

‘Homebound, came down 2km east of Luckenwalde and exploded with great force. Three lie in Berlin 1939-1945 War Cemetery and four are commerorated on the Runnymede Memorial. S/L Bickers was on the third sortie of his second tour. At 21, he was one of the youngest flight commanders to be killed in Bomber Command during 1944.

There may be no finer epitaph to Ken than that contained in Don Charlwood’s gripping first-hand account of life as a Bomber Command pilot, ‘No Moon Tonight’, in which the author describes coming across Ken shortly after his DFC exploits detailed above:

‘In the morning I heard that Bickers’ crew had had a shaky do the night before. The rear gunner had been killed and for ‘Bick’ himself there was talk of an immediate DFC. Their plane had been attacked by fighters and damaged beyond belief. In the crew room ‘Bick’ was being congratulated. To everyone he gave the same brief answer, ‘It was a crew show. The way they stuck together got us back.’

‘Looking at Bickers, I felt that in him our last seven months were typified. For a Flight Lieutenant he was more than usually young. His face was finely formed and unsmiling; his eyes direct. And in his eyes was that enigmatical ops expression I had noticed so often before. I wondered what he had been before the war. I thought of him as a bank clerk, university student, even a schoolboy, but each was poles removed from the Bickers before me.’

‘It was as though he had been created to wear the battered ops cap; the battle dress with its collar whistle; the white ops sweater; to be a man to whom years did not apply. But most of all, it was as though he had been created for this very hour, to stand in this drab room of many memories hearing the congratulations of his fellows.’

2. The Search

My father (Ken’s younger brother by four years) has always been immensely affected by Ken’s death – indeed my own middle name is Kenneth in tribute. However it has only been in the last few years since the death of my Mother that I have become acutely aware of just how much he has been affected, and one day earlier this year whilst were discussing the subject, I realised that the only way for him (and me now) to try and find some peace would be to visit Luckenwalde and see if we could find the exact spot where Ken’s Lancaster had come down, we had no clues, other than the statement from the official record of Bomber Command Losses stated above, but by visiting we would at least gain some sense of time and place and how it all must have happened.

My Father was sceptical, worrying about the reaction of the local populace, but eventually I managed to persuade him to go, and I booked the flights from Liverpool to Berlin. It was only after I had booked them that I realised with amazement that the date of our flight to Berlin was 24 March 2015 – exactly seventy-one years to the day of Ken’s fateful flight. We took this as a sign that perhaps what we were doing had merit after all, and upon arriving in Berlin we picked up our hire car and drove to our hotel in preparation for the search ahead.

The next day we drove initially to Luckenwalde, a small friendly town about twenty kilometres south of Berlin near where Ken’s plane came down as described above. We decided to visit the local museum to see if we could find any clues as to the actual crash site, and eventually we were ushered upstairs to meet the Curator, a Herr Schmidt, not your average looking Curator it has to be said, looking very hippy-dippy with Panama hat, pony-tail and goatee beard (!), and also with no English, but he did everything he could to help, digging out old photos of the time showing the aftermath of the bombing raids and even producing a logbook that had noted in it details of all the bombing raids in the area. Ken’s raid was there right enough, but no details were available of the actual crash site, so we adjourned for a delightful German coffee and ice-cream next door and decided on our next move.

We knew that the Lancaster had come down somewhere between Luckenwalde and the neighbouring much smaller village of Janickendorf, so we determined to drive to Janickendorf to see if there was any visible evidence of the dreadful event all those years ago – unlikely but we had a lot of time on our hands .

The village of Janickendorf is very spread out, and to drive through it takes a good three or four minutes – at the far end is an industrial estate and next door is an overgrown piece of land full of bumps and hillocks, and we surmised not unreasonably that the undulations could well have been caused by a plane crash, so we decided to lay a cross in memory of Ken and his crew at this location, and set off to drive back to our hotel.

However I think we were both feeling frustrated by the fact that we didn’t know for sure that we had found the actual crash site, and on our way out of the far end of the village I happened to glance to my right and saw a gentleman walking up a side road towards the main road we were driving along, so I suddenly said to my Father ‘I’m going to stop and see if he might know something’ , pulled over about a hundred yards further along the road and got out to walk back to talk to him. The fact that I knew only about a dozen words of German wasn’t going to put me off !

By the time I got back to the gentleman he had crossed the road to the other side, and was talking to two other people, but I looked to my left and I saw a quaint building with the word ‘Museum’ (or the German equivalent !) on it – the barn door was open, and at that exact moment a lady emerged – so I changed tack and walked over to the lady, intercepting her as she was about to close for the day. I asked if she spoke English, and as I did so I glanced into the museum – to my utter shock there in front of me was a piece of the framework from Ken’s Lancaster, together with a list of him and his crew, and depictions of what the aircrew would have been wearing at the time. I think my reaction and the way I was looking at the artefacts made the lady understand, because she then beckoned to the original gentleman I had seen (who turned out to be her husband!) and called him over together with a young lady who was able to speak English, and suddenly all became clear. At this point my Father was still in the car, so I raced back up the road, opened the door and said words to the effect of, ‘I think we might have found the plane’.

My Father of course couldn’t believe it – when he walked into the museum for the first time and saw the piece from Ken’s Lancaster it was a very emotional moment. The German couple, Manfred and Gisela Bolke, welcomed us with open arms, and Julia Horn (the young lady) translated. We were offered tea and cake in the Museum, and gradually our story unfolded, much to the amazement of our German hosts who could not have been more welcoming and understanding.

During our conversation, Manfred said that there was a Herr Kruger that he would like us to meet – when Julia explained that this other gentleman was the boy who as a fifteen year old had found the remains of the crashed Lancaster we were stunned, and agreed to come back on the morning of our departure back to Liverpool to Manfred and Gisela’s house to meet Herr Kruger from where he would take us to the actual crash site.

So the next morning we returned to meet Herr Kruger at Manfred and Gisela’s house which is located just over the road from their private museum. On this occasion Manfred and Gisela’s grand-daughter Christina joined us in order to be able to translate which she did incredibly well in spite of a lot of technical jargon !

Herr Kruger is now eighty-six years old but he was able to recall the events of that day as if they had happened yesterday. After the initial introductions and a brief discussion Herr Kruger said he would take us to the crash site, and we all got into Manfred’s car (Julia now having rejoined us to take over translating duties from Christina) and drove about a kilometre out of the village (in the opposite direction to where we had laid the first cross) and turned right up a small narrow lane. At the top of the lane we turned right again and entered a wooded area, dense with trees on both sides, the lane became ever bumpier until eventually after about five minutes Herr Kruger asked us to stop.

We got out of the car and with Julia translating Herr Kruger told us his story. He described how as a fifteen year old at six o’clock in the morning he and his ten year old sister had come to the crash site where we were standing to see what had happened. He pointed to the ground and told us that it was at this exact spot that he had found the dead body of a British airman, and said that he was struck by the fact that a lot of his clothing had been torn off but how clean his socks were. He was able to show the exact angle at which the body was lying (this body would either have been Air Gunner Tombs or Air Gunner Cannon, both of whom are buried at the Berlin War Cemetery).

Of course at this point we were reeling with the amount of information that he was telling us, because he was making it all so real. Herr Kruger then requested that we get back in the car, and we drove a further five hundred yards or so before getting out once again. This time we walked through the trees and dense bracken to the edge of a vast field which was sewn with crops. It was here, said Herr Kruger, that he found a second body, and heart-rendingly and with great emotion he said he felt that this airman may still have been alive when he hit the ground, as there was evidence of the soil having been disturbed by the movements of one of his feet, and in his hand was a photograph of his wife and children which he must have taken out of his wallet to look at before he died (this body was probably that of Flight Engineer Wadsworth).

Herr Kruger pointed to the vast open expanse of the field and told us that this was where the bulk of the Lancaster had hit the ground. He was able to show us a photograph that he had taken of his sister in front of what looks like one of the propeller sections. He had made it all so real, and we were so very grateful. My Father laid another cross at the foot of one of the trees nearest the field (no remains of the other four bodies including Ken were ever found) and we all stood together, united in our remembrance and sadness for what had occurred here seventy-one years ago.

We then repaired to Manfred and Gisela’s house where Gisela had prepared a delightful tea and cake, and we were able to have further conversations (Julia now having left us) by virtue of the Google translator which Gisela had set up on her laptop ! Herr Kruger had driven around sixty kilometres to be with us that morning, and we are indebted to him and of course to Manfred, Gisela, Julia and Christina for the wonderful welcome that they afforded to us, which bearing in mind we had arrived out of nowhere only two days previously was nothing short of incredible.

However the story didn’t finish there. Upon our return to England, again by the use of the Google translator and email I corresponded with Gisela, and suggested to her that we might like to come back at a later date with a metal detector to see if we could possibly find any further remnants belonging to the downed Lancaster or perhaps any personal possessions relating to the dead airmen. Gisela immediately wrote back and said that they already owned two metal detectors, had been in touch with the farmer for permission to search his land and they were going to do so in a week’s time ! Words can’t do justice to the way we felt about this.

A week or so later Gisela sent us some photographs of Manfred and a younger couple with their young son all fervently engaged in metal detecting on the field of the crash site – they had unearthed several mainly agricultural items but as yet nothing that could be said to be from the Lancaster. However more intriguingly Manfred had taken a photograph of a piece of rusted metal embedded halfway up a tree which looked as though it could have come from a plane as it was slighted rounded in appearance.

Ken’s Story Continued…

Once we had returned from Germany, we continued our correspondence with Manfred and Gisela via email, and it quickly became apparent that they were determined to help us as much as possible, not only in searching for any remnants of the lost aircraft and its crew, but also in taking full responsibility for planning and organising a dedicated memorial plaque in honour of the lost airmen.

One day a parcel arrived for my Father from Germany – contained within it were a small part of the Lancaster’s fuselage, and more poignantly a part of a leather boot – we were incredulous!

My Father and I asked Manfred and Gisela if it would be possible to install a memorial plaque at the crash site, and they immediately began making enquiries of the German authorities as to whether or not this was permissible. When the answer came back that it would not be possible, Manfred and Gisela nevertheless kindly agreed that a plaque could be put up in front of the museum in Janickendorf which is only about a kilometre away from the actual crash site.

Over the next few months the design for the plaque took shape, thanks to Karl Spath, a well-known designer from Luckenwalde, and as the project progressed it became apparent that it would be most appropriate to unveil the plaque on the anniversary of the Lancaster’s demise, 24 March 2016. The timetable was very tight, but the determination of Manfred, Gisela and Karl together with the help of many friends and neighbours knew no bounds, and on 22 March my Father, son and myself travelled to Germany for the unveiling of the plaque on 24 March.

In the meantime by chance we had been put in touch with the grandson of Norman Tombs, one of Ken’s crew members also killed on that fateful day. Mel Taylor and his daughter Rebecca met us at our hotel in Luckenwalde on the morning of the ceremony and we exchanged many fascinating stories about eachother’s families before proceeding to Janickendorf.

The ceremony itself was very moving, and wonderfully organised by Manfred and Gisela. A violinist played some very moving music, and short speeches were given by the Mayor of Nuthe-Urstromtal, Gisela and myself, and then the plaque was unveiled by Manfred and Karl, a very moving moment.

The eyewitness of the time, Herr Kruger, was once again with us and following the ceremony we travelled to the crash site where Herr Kruger was able once more to tell us what he had found on that March day back in 1944. His emotion and distress were evident to all and we are very grateful for his sincerely held memories.

We then paid our respects at the tree adjacent to the crash site where Manfred and Gisela had put up a portrait of Ken along with the remembrance cross that we had left on our previous visit.

A year to the day after first stumbling across Manfred and Gisela , a permanent monument to the fallen airmen now stands outside the museum in Janickendorf, thanks to the unswerving efforts of Manfred and Gisela themselves along with all of their colleagues. It has been a magnificent achievement by them and an emotional journey for us – we thank everyone from the bottom of our hearts.