The Dutch authorities had only one day’s notice in which to arrange for the actual collection of the food once it had hit the ground, and to arrange for its transportation from the fields. There were six designated drop zones: Valkjenburg airfield (Katwijk) , Duindigt Racecourse and the Ypenburg Airfield (The Hague), Waalhaven Airfield and Kralingse Plas (Rotterdam) and Gouda. To each of these an air corridor had been agreed under the terms of the ceasefire.

Food being transported from the drop site to The Hague

It was reported by a member of the first crew that flew, that at Terbregge in the Rotterdam area, not even a horse drawn cart could enter the enormous field and thousands of men had to manually collect and carry the food by hand. First Aid posts were also set up across the country as there was a real fear of food parcels actually striking and injuring the people in the fields, who were awaiting the arrival of the aircraft. The Germans decided that anti-aircraft guns would be placed at certain drop sites as a precaution. The idea was that they could react immediately if it turned out that the Allied aircraft dropped paratroopers instead of food!

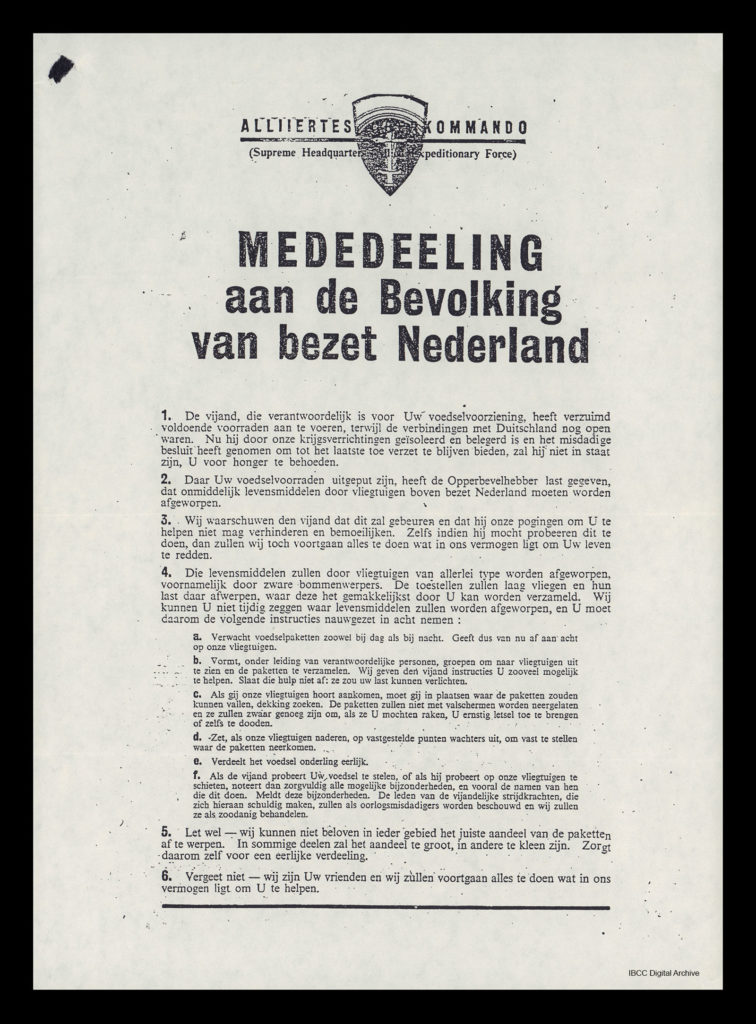

Leaflets like this were delivered to alert the population, help was on its way

Food packs included tinned items, dried food, tea and coffee and chocolate. After much testing of different packaging, hessian sacks were used, some of which were sourced from the US Army.

The ceasefire was signed on the 30th April. Operation Chowhound, the US Army Air Forces aid drop, started on the 1st May and delivered a further 4,000 tons of food. This was followed, on the 2nd May, with a ground based relief mission, Operation Faust. It is estimated that these drops saved nearly a million Dutch people from starvation.

The Dutch showed their gratitude for the drops in a number of ways. Here marked with empty food bags

Three aircraft were lost during the operation, two in a collision and one suffered an engine fire. Despite the ceasefire, several aircraft returned with individual bullet holes, assumed to have been fire from individual German soldiers.

For more images from Operation Manna click here

Hear an account of the Op by Norman Wilkins here and an interview with the world’s leading expert on Op Manna, Johannes Onderwater here