In March 2025, the IBCC unveiled an installation honouring the service of women in WW2. The display includes 10 women, covering different sectors and with vastly differing stories. What they all had in common was the selfless contribution they made to the war effort. The exhibition, which is located around the Memorial Spire, will be in place for the foreseeable future and is free to visit.

Ten outstanding wartime women

These ten women have been chosen by the IBCC to represent the contribution, courage and leadership shown by women at all levels during the Second World War. Each is being supported by modern giants – women who are making an enormous contribution today.

Joan Curran – a brilliant physicist who graduated from Newnham College in 1937 but was not awarded a degree because Cambridge still refused to grant them to women. Undaunted, she secured a special grant to study for a higher degree and in wartime was critical to many technical developments, notably the proximity fuse and the invention of “Window” – the use of chaff to confuse enemy radar. Window was dropped by Lancasters of 617 Squadron to synthesise a phantom invasion force of ships in the Straits of Dover and keep the Germans unsure as to whether the brunt of the Allied assault would fall on Normandy or in the Pas de Calais. Her husband, another wartime physicist, was knighted – but a senior contemporary scientist gave it as his opinion that she made a greater contribution to the war effort than he did…

Dorothy Robson – who died aged 23 on a short mission to check the bombsight on a new aircraft. She was a physicist and engineer responsible for developing the tools for precision targeting, saving much collateral damage from ill-directed bombing. She wasn’t tall enough for the WAAF, so joined up with the Royal Aircraft Establishment. Known as “the girl with laughing eyes”, or “Bombsight Bertha”, she spent much of her short life studying bombing photographs and at her request her ashes were scattered over Yorkshire from a small 76 Squadron aircraft she herself had occasionally flown.

Muriel Blake – one of many women who carried out the critical but difficult task of packing the huge life-saving silk parachutes into aircraft. An Oakham girl, she worked in a restaurant in Leicester and then volunteered for the WAAF. She was at first rejected because of a hammer toe and turned down as a driver because she only weighed six and a half stone. She became a safety officer, working to pack and load parachutes and dinghies. At RAF Mepal it was a tradition that any aircrew who bailed out successfully came to check from the records who had packed their parachutes and give them a pound for their lives, a sum roughly equal to their week’s pay. She was injured packing the heavy dinghies and suffered from that all her life.

Renee Woods – Renee was born in Fishtoft, near Boston, Lincolnshire. She was killed whilst serving at RAF Waddington when 5 Nazi bombs dropped from a lone Luftwaffe bomber destroyed the NAAFI on 9th May 1941. She was only 23 years old.

Six NAAFI girls were killed in that raid including Manager, Doris Constance Raven. The rebuilt NAAFI building was christened the Raven’s Club in their memory and retains that name to this day.

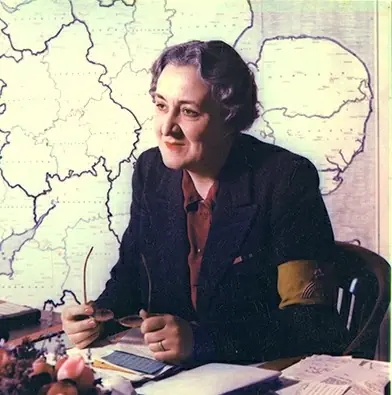

Stella Charnaud – philanthropist and founder of the WVS. Her mother, Milibah Johnson, came from Lincolnshire and was the second wife of Charles Charnaud, who was working in Constantinople when she was born. After the first world war, in which she worked as a volunteer, she became secretary to Lady Reading, the wife of the Viceroy of India. later becoming the Viceroy’s Chief of Staff. After the Marchioness died from cancer, Stella married the Marquess of Reading, and when he died in 1935 became even more involved in public work and a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1938 she responded to the Home Secretary’s request to form a women’s organisation in case of war, and founded the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS), which by 1942 had a million members. She later founded Women’s Home Industries and became the first woman to take her seat in the House of Lords as a life peer in 1958.

Molly Evershed – Among the 22,442 people who lost their lives serving under British command on D-Day and during the Battle of Normandy, two were women.

27-old Sister Mollie Evershed and Sister Dorothy Anyta Field, who was 32, were both nurses. They were serving with the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service.

Molly was born in Soham, Cambridgeshire in 1915. She joined the Queen Alexandria’s in 1943 and was aboard HMHS Amsterdam on the night of 7th August 1944 when it hit a mine off the Juno Beach. She was killed along with 105 others.

Lettice Curtis – the first woman to fly (and deliver to operations) a Lancaster bomber. Educated at Benenden and St Hilda’s, Oxford, where she studied Mathematics, she became one of the first women pilots to join the British Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). Between 1940 and 1945 she was said to have flown “thirteen days on, two days off” for 62 consecutive months, piloting a vast range of aircraft. After the war she worked for a number of years on the initial planning of the joint civil/RAF Air Traffic Control Centre at West Drayton. She was a founding member of the British Women Pilots’ Association and qualified to fly helicopters in October 1992 – before voluntarily “grounding” herself in 1995.

Margaret Hourigan – a miner’s daughter, who saw much privation during the Depression as she grew up in Nottingham in the 1930s. She volunteered for the WAAF when she was called up in 1940 and became a Plotter with Fighter Command. She was promoted to sergeant on her transfer to Bomber Command and served at both RAF Waddington and RAF Skellingthorpe, working in a big ops room at the Doddington end of the station. She was mentioned in dispatches and at the end of the war met and married an Australian pilot and emigrated to Australia.

Matron Dorothy Anyta Field – Anyta died saving the lives of 75 wounded servicemen on the hospital ship SS Amsterdam in August 1944 along with Sister Mollie Evershed. They were the only women out of 22,442 people under British Command who lost their lives during the Battle of Normandy. She came from.

Dorothy – better known by her middle name, Anyta – was born in Lower Kingswood, Surrey and trained at King’s College Hospital, London, qualifying in November 1935. She joined the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing at the outbreak of war.

When the Amsterdam was hit on the 7th August 1944, she returned from her lifeboat to help save the servicemen trapped on the ship and died when it sank. She was 32 when she was killed.

She was posthumously awarded the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct.

Madeleine Damerment – a Frenchwoman who was involved in the Pat O’Leary escape line, one of the first of these lines which helped an estimated 7,000 downed allied airmen escape from occupied France. She herself helped as many as 75 airmen but fled France in March 1942 to avoid arrest. After arriving in Britain, she was recruited by the SOE, to be trained to become a courier for SOE’s Bricklayer circuit. But she was captured by the Gestapo on her return to France and executed at the Dachau concentration camp on 13 September 1944 along with three other female SOE agents.