OP EXODUS – BOMBER COMMAND’S FORGOTTEN OPERATION

Written by Peter Allam

The word ‘Exodus’ is derived from the Ancient Greek word ‘éxodos’, literally meaning ‘way out’. Known throughout the world as the title of the second book of the Bible, Exodus recounts the release of the Israelites from slavery and their journey to the Promised Land. For obvious reasons, World War Two operation code names were usually chosen which bore no relation to the actual nature of the operation. However, biblically inspired names were occasionally chosen with Operation Manna (the dropping of food to the starving Dutch people) being perhaps the most well-known example. In April and May 1945 RAF Bomber Command carried out another humanitarian operation, the repatriation to the UK of tens of thousands of recently released British and Commonwealth POWs, and for this another wholly appropriate biblical code name was chosen – Operation Exodus.

With the war in Europe obviously entering its final stage, in March 1945 planning began for the soon to be essential and prompt repatriation of the thousands of POWs, who were then still held in a number of camps scattered across Germany. Initial thoughts were centred around seaborne transportation, but it soon became obvious that with the future availability of useable shipping ports still uncertain, this could potentially take much too long and be fraught with difficulties. Inevitably some of the POWs would be in poor health and physical condition, making speed of the essence. Because of this the planning focus which was shared between the British War office and SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force), shifted from evacuation by sea to a huge airlift.

With prisoners spread across Germany it was necessary that a handful of key focal airfields be identified at which the POWs could be assembled prior to air repatriation. In Germany itself, Lübeck on the Baltic coast and Rheine near the Dutch border were both selected, while in Belgium, Melsbroek (nowadays Brussels International Airport) also became a collection point. In France, Juvincourt near Reims and Lille in the northeast of the country completed the Continental airfields. In the UK, a number of Normal and Reserve Reception RAF airfields were identified, the former group including Dunsfold, Ford, Methwold, Seighford, Westcott and Wing, and the latter group Oakley and Tangmere. At each of the reception airfields a hangar was assigned and equipped with all the staff and facilities necessary to receive and process thousands of former POWs. The Red Cross playing a significant role, as did many of the other war relief organisations.

By March 1945, the Dakotas of RAF Transport Command’s 46 Group had already been engaged in casualty evacuation flights for many months, and with the ground war winding down and casualties decreasing, the group’s aircraft were considered eminently suitable for a POW recovery operation. Although not actually a part of Operation Exodus, the air repatriation of POWs began on 3 April when seven 46 Group Dakotas landed with their precious cargo at RAF Oakley near Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire. Although still carrying out airborne operations in Denmark and Norway, a number of 38 Group Stirlings and Halifaxes were also released shortly afterwards, beginning POW flights on 17 and 18 April respectively. Transport Command flights continued for some time, eventually accounting for a total of 58,000 POWs repatriated to the UK.

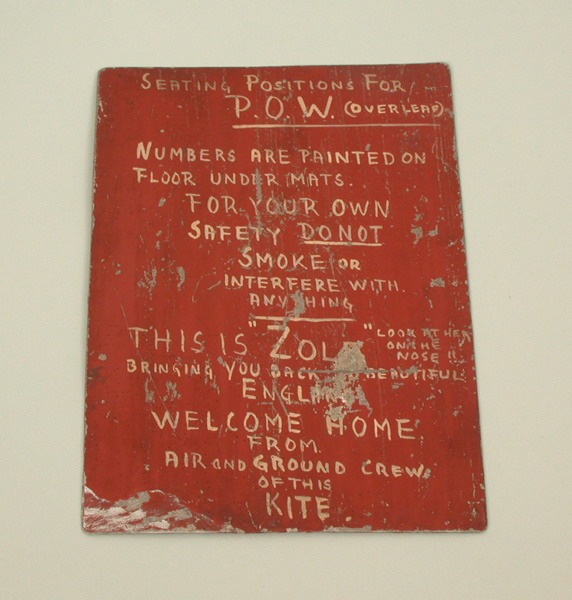

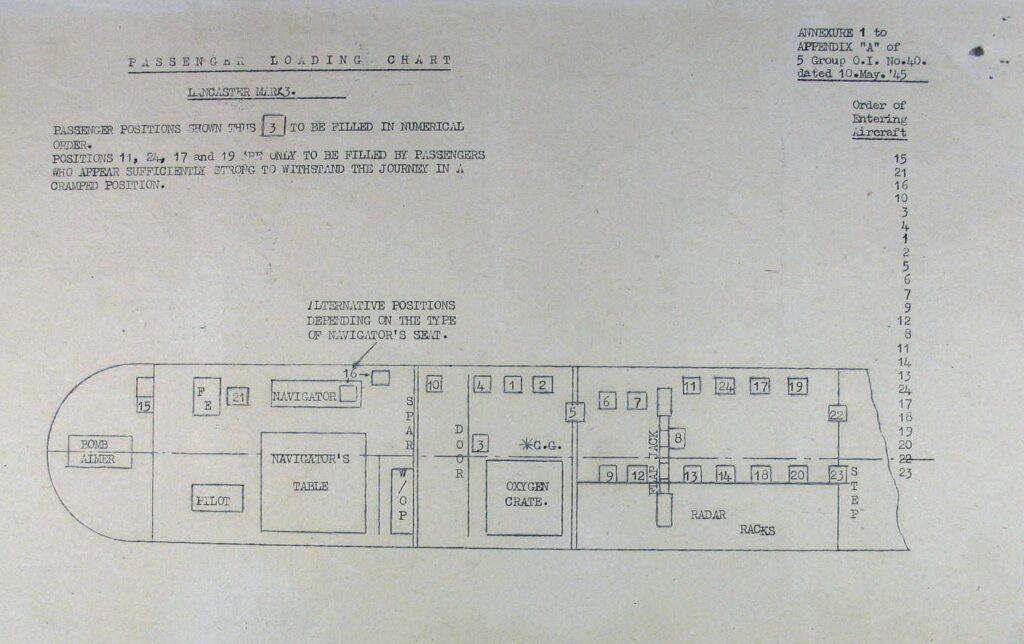

It was also obvious to all concerned that the massive resources of Bomber Command would also soon become available, and planning began for the use of Lancasters under the code name Operation Exodus. On 26 April, the very same day that 107 Lancasters returned from the RAF’s last heavy bomber raid of WW2 on an oil refinery at Tonsberg in southern Norway, Operation Exodus commenced when Lancasters of 50, 61, 463 & 467 squadrons repatriated dozens of POWs. Although the spartan confines of a Lancaster were less than ideal for carrying passengers, helped by the provision of blankets and cushions, each aircraft was able to carry a maximum of twenty-four POWs. As the Lancasters usually also had their normal crew of seven on board, and even though in many cases the POW’s possessions amounted to nothing more than the clothes they were wearing, thirty-one people squeezed inside a Lancaster is nevertheless hard to imagine.

All aircrew who took part in Exodus were left with some indelible memories, and the author’s father W/O A J ‘Bert’ Allam and his 227 Squadron crew were no exception. Flying their favourite Lancaster Mk.I PA283 9J-J (known to the crew as ‘The Jabberwock’ after the nonsense poem in Lewis Caroll’s ‘Through the Looking Glass’), the crew were assigned an Exodus trip to Brussels in the early afternoon of 10 May. After taking off from their base at RAF Strubby in Lincolnshire and flying directly across the North Sea, landfall was made at the Dutch island of Walcheren, as Bert Allam recalled in his unpublished memoir:

‘We crossed the shore near the Westkapelle light and flew on over one of the saddest looking scenes we had ever come across. During October, Lancasters of 5 Group broke down the sea wall in several places, and when the Allied offensive was finally launched, German resistance came to an end after only ten days on November 10th. Now, six months later, the island looked very much as it must have done following that November struggle.

Alongside us on the starboard side the untouched sea wall ran southwards forming the only high ground on that side, and way over to port the spires and roofs in a distant untidy cluster marked the corpse of Middleburg – chief town of the island. The entire scene was one of utter desolation. Not a living thing could we see; below us was a dead world; a world of water.

It all seemed so quiet. I know that sounds silly considering we had four Merlins hammering away in our ears, but looking down on the land below it did seem quiet, with no life and not a sign of movement anywhere. Even the sea, having done its worst, seemed content with the havoc it had wrought and was itself lying still. It was perhaps the loneliest sight I have ever seen on earth and surely a symbol of the stupidity of man. For some time, no one said anything. Then at last Matt (Bomb Aimer Denzil ‘Matt’ Matthews) spoke.

“I wonder whether all that was really necessary?” he said.

We didn’t reply. There didn’t seem much to say. We were all a little stunned by it all. This destruction of the land itself – handing back to the sea this expanse of hard-won fertile countryside seemed somehow particularly futile.’

After overflying the southern part of the Netherlands, the crew soon crossed into Belgium, and before long they had arrived at Brussels and joined the circuit at Melsbroek:

‘We didn’t fly right over Brussels but instead made for Melsbroek airfield which we picked out easily when some miles away. There were a number of aircraft in the sky in the vicinity and appeared to be many more parked on the ground alongside the runways. The runway in use was the long one running as far as I remember roughly north-east to south-west, and the direction of landing when we arrived was to the north-east. It ran alongside and almost parallel to the perimeter track, and on that side of field about halfway along its length a column of black smoke rose high into the air from what at first sight appeared to be a small building on fire.

As we flew over it we could see that it was indeed a building of some sort, but the reason for the blaze was a Lancaster which was piled up on top of it. The whole lot was blazing furiously, belching black smoke, and only the tail unit and rear part of the fuselage was now recognisable.

One or two trucks stood nearby whilst a group of men seemed to be doing little – apparently content to let it burn itself out.’

On landing the reason for the crashed aircraft soon became obvious, the heavily bomb damaged and poorly repaired runway being in a terrible state, with a second Lanc also parked at a drunken angle with a burst tyre, close to the worst part of the runway. Incredibly, the same group of twenty-four POWs had been on board both aircraft during the two attempted take offs. In the first incident RA595 of 101 Squadron burst a tyre and ground looped, and then after boarding the second aircraft (ME623 of 97 Squadron), the POWs had a much closer shave when the aircraft swung off the runway, crashed heavily into an airfield building and burst into flames. Although badly shaken, fortunately all on board managed to scramble clear with nothing more serious than bruising.

After being marshalled into their parking spot the crew reported to flying control, in order to receive their instructions for the return flight. As the afternoon wore on it looked as if there wouldn’t be enough POWs to make up a load, and the Allam crew were beginning to look forward to a night on the town in Brussels. However, some of the POWs who had survived the two take off accidents were still on the airfield, and one of the marshalling officers tentatively enquired if any of them felt like seeing England that night. Some quite understandably refused point blank to attempt to fly again, and offered some highly original but unprintable suggestions as to exactly what the RAF could do with their Lancasters, but others were so desperate to get home that they agreed to give it a third try.

Once the POWs had been helped into their ‘Mae Wests’ by the crew and shown to their positions inside the aircraft (each marked by a painted number), the author’s father started up and taxied carefully to the end of the active runway:

‘I went over my vital action check with particular care, and getting permission to take off I released the brakes and slowly eased the Lanc on to the narrow connecting strip. Then I decided to start my take off run from where I was and so gain an extra few yards.

Reaching forward I pulled the boost over-ride lever down to give maximum emergency take off power, and holding the brakes on, opened up to zero boost – then with brakes released pushed the four throttles smoothly forward in a staggered line and on through the gate.

Steve (Flight Engineer Len ‘Steve’ Stevens) locked the throttles as I held the stick well forward to bring the tail up quickly. We raced on down the runway, jolting over the uneven surface – and then it came – a mighty bump which projected the aircraft off the ground as we hit the danger spot. Instantly I eased the stick back and nursed the Lanc along in a mushy half stalled condition a foot or so up, slowly building up the airspeed until we were at last flying comfortably and climbing steadily away – albeit feeling a little unwieldy due probably to the unfamiliar distribution of weight. At least we had made a clean take off and the boys could breathe again.’

A more southerly return route took the Lancaster home across northern France and the English Channel, and after the dramatic takeoff the POWs soon settled down and began to enjoy the trip. The rest of the return flight was uneventful, that is until when nearly across the English Channel the 500ft high white chalk cliffs of the Sussex coast came into view:

‘At last, through the slight haze which surrounded the sun, the English coast appeared as a blur in the distance, and I think we all felt that the moment of the day had arrived.

As many as could crowded forward to catch the first sight of England, and after the initial buzz of excitement, stood watching that smudge of a line gradually merge into the recognisable outline of Beachy Head.

I looked at their faces as they peered out wide-eyed. What were they thinking, I wondered? Steve caught my eye, and I knew instantly that his mind was on the same thing – wondering what it felt like to these poor chaps – seeing once more the country they had left – long ago in many cases, for we had some veterans from Dunkirk and even earlier – and now to which they were returning at last to within reach of their families and homes.

I glanced at some of the aircrew among them. A W/Op from 4 Group. A navigator from our own 5 Group. What were they thinking? When they had last crossed this coast, they were on what was to be their last operational trip.

We were now close in and although the light from the setting sun reflected awkwardly from the water we could see the downs of Sussex quite clearly. Someone pointed out Eastbourne pier and that did it. The spell was broken, and everyone had something to say.

The aircraft was quite a sight just then. We had half a dozen up front by the bomb aimer’s position, more by Steve and Tiger’s bench, some in the astrodome and in the rear and mid upper turrets – and as there were still some who couldn’t see out, I opened the bomb doors as we came over Eastbourne and they took it in turns to look out through the rear inspection panel. It was a grand moment.’

After landing at RAF Westcott in Buckinghamshire (the author’s father recalled that he didn’t think he ever tried harder to make a good landing!), the exhausted but ecstatic and relieved POWs were safely delivered to the waiting reception staff. Although they had only been together for a few hours the Allam crew already felt an attachment to ‘their’ POWs, and it was with some regret that they parted company, before taking off and heading back to Strubby.

‘Several other Lancs were taxying out with nav lights on and mingling with them were the bulky low-slung shapes of the resident Wimpys – off no doubt on a cross-country trip. Watching them rumble out our thoughts went back to our own OTU days. Well, they had a grand night for their cross-country – but they were welcome to it. For us it was home and bed.

Starting up we moved out and filtered into the queue behind a Wimpy and crawled around the perimeter, the blues and ambers of the taxy track peeping through the gaps between the aircraft.

Darkness was well upon us and the aircraft were outlined sombrely against the western sky where the last trace of day was fading.

Sitting on the end of the runway, I warned the crew to stand by for take off, and as the Wimpy ahead of us cleared the distant fence there came a steady green from the caravan and I pushed the throttles forward.

As soon as the wheels lifted, I went into a climbing turn onto course and in a few moments, we were back at a thousand feet and heading homewards.

The night air was still and wonderfully smooth. Having adjusted the trim, the Lanc flew hands and feet off with hardly a tremor of airspeed or compass needle.

Tiger (Wireless Operator Harry ‘Tiger’ Gaunt) leaned over my shoulder and gave a nod of approval. He seemed pleased at something, and it wasn’t hard for me to guess why he was so. It had been a day to remember. A day in which we felt we had done something really worthwhile.

At any rate I know I was quite contented as I sat there letting the Lanc fly herself home.

Tiger was happy. We were all happy. It had been a happy trip.’

Operation Exodus reached its peak in mid-May, at which point over one thousand ex-POWs were arriving in the UK each day, with a Lancaster touching down every four minutes. The airlift eventually came to a close on 4 June, when four 138 Squadron Lancasters collected a final load of POWs from Juvincourt and delivered them safely to Dunsfold. The air repatriation had been a resounding success, and in addition to the aircraft of 38 and 46 Group, a number of British and Commonwealth POWs were also transported by aircraft of the USAAF’s 8th and 9th Air Forces. RAF Bomber Command eventually committed forty-seven Lancaster squadrons to Operation Exodus, flying some 3,500 sorties and repatriating 74,195 former POWs, well over half of the eventual total of 132,000 British and Commonwealth servicemen repatriated by air to the UK.

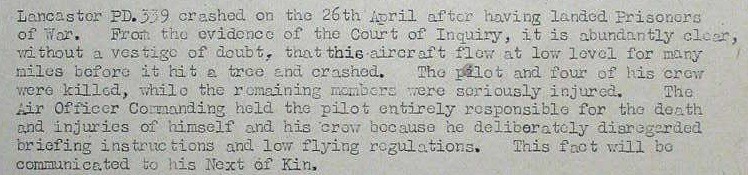

Very sadly this incredible achievement was marred by several fatal accidents; three ground crew, eighteen aircrew and particularly tragically twenty-five former POWs were killed, with ten Lancasters being completely destroyed and another eighteen damaged to varying degrees. It might have been both hoped and expected that with the war over at last, safety was finally within the grasp of all involved with Exodus. But incorrect loading, technical failures, bad weather, unsuitable runways in poor condition and also (regrettably) unauthorised low flying accidents, all played their part in the losses.

In spite of the operation’s success, eighty years on Exodus remains a half-forgotten footnote in the history books, forever in the shadow of the more well-known Operation Manna. And while Bomber Command’s other more famous humanitarian relief operation is rightly commemorated both in the UK and the Netherlands, sadly there remains no known memorial to the POW airlift. But for all those who took part, whether they were former POWs or Lancaster aircrew, the events of April and May 1945 and the name ‘Exodus’ would remain indelibly etched in their memories for the rest of their lives.